The 1960s hippie ideals of peace and love are not only naive and unfashionable but also laughably out of reach in today’s political climate. From Mark Bradford’s crumbled White House at the Venice Biennale to the depressing banality of the 9th Berlin Biennale exhibition, hopeful artistic visions seem to only appear in nostalgic subjects such as Kehinde Wiley’s and Amy Sherald’s Obama portraits.

It is, then, an intriguing time to revisit a work from Yoko Ono, who has created (and continues to create) work that is occupied with fostering intimacy and unity. Until March 31, 2018, Vancouverites have the opportunity to engage with Ono’s Mend Piece, Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York City version (1966/2015) at Chinatown’s Rennie Museum.

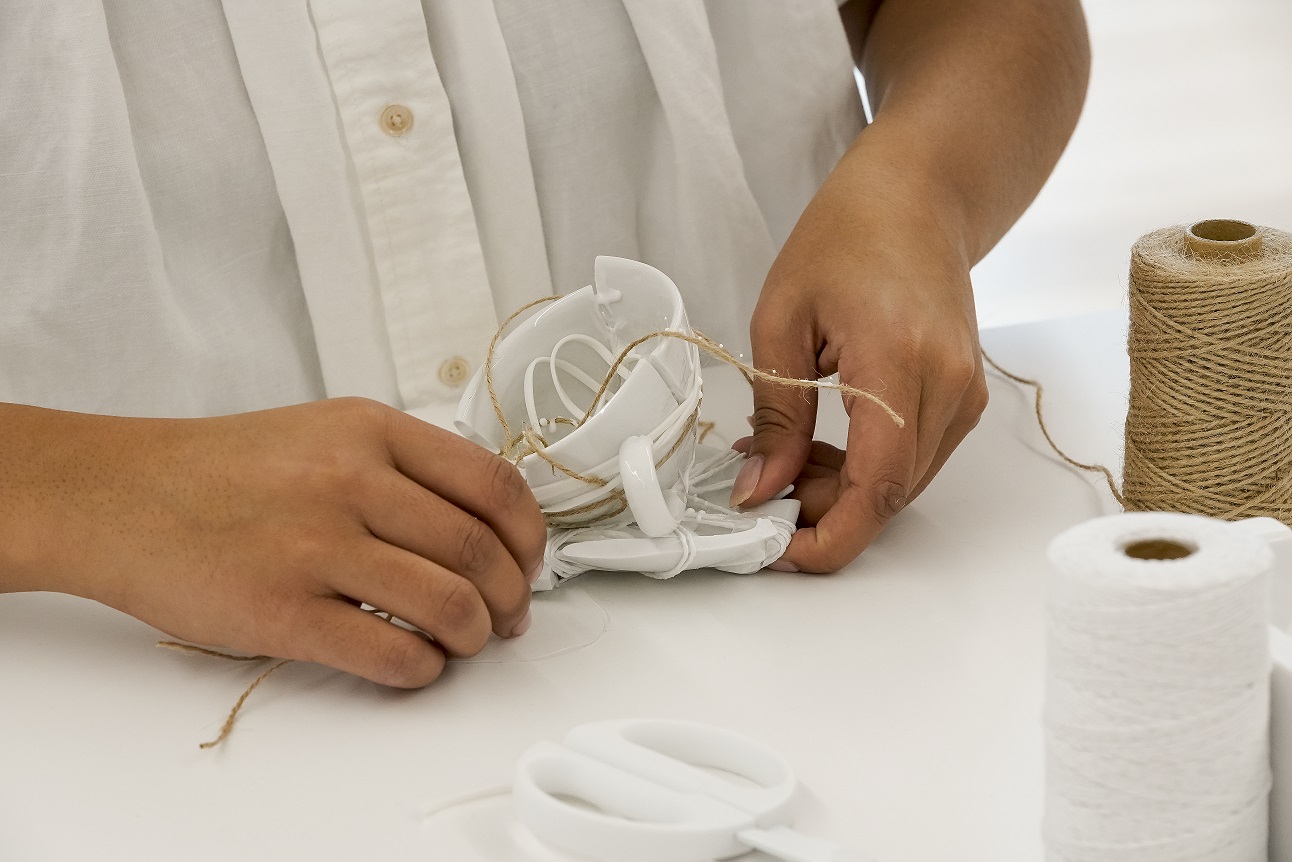

Ono, the widow of John Lennon, first came to prominence in the 1960s as part of the influential Fluxus movement in New York City. Works such as Cut Piece, where audience members were instructed to approach the artist and snip pieces of her clothing off, are critical offerings of performance art. Ono’s creations often include instructions, as is also the case with Mend Piece. The work, which was acquired by Bob Rennie’s collection in 2016, includes instructions for the gallery to supply a white table, white scissors, glue, tape, string, white rubber bands, shelving, and broken cups (Rennie sourced from Ming Wo). Participants, who book a session through the museum’s website, are then loosely instructed to take the cups and put them back together. Their fixing is up for individual interpretation, and the end results are placed on the display shelf after the session. The metaphor is a simple one: fix a broken tea cup—a vessel that signifies sharing and community—and begin to heal relationships.

The piece was first conceptualized by Ono in 1966 when politics in the United States had begun to turn to the anti-Vietnam War movements. Ono met Lennon during the same year, and their life together was devoted not only to each other but to their aspirational politics, culminating most famously in their 1969 Bed-In at the Hilton in Amsterdam and Fairmont The Queen Elizabeth in Montreal. Mend shows Ono’s practise opening up to broader socio-political issues and turning her focus from the gallery or museum viewer to participants of a larger scale. Ono would later become even more bold in her rhetoric and audience, creating, with Lennon in 1969, billboards proclaiming that “WAR IS OVER! if you want it.”

In Mend Piece, we are asked to question our limitations as spectators within the art gallery context, as explored in Ono’s early conceptual work—what can be touched, who is the artist, what is the artwork—while beginning to engage with larger concepts of socio-economic and community equity. Experienced while seated at the table with friends and strangers, Ono’s piece directly encourages community engagement; and set within Chinatown, it’s difficult to ignore the fact that we are so disparately divided on the question of what community is and means.

Like in much of Ono’s oeuvre, Mend takes on much more complicated and multi-faceted understandings when it enters into a real-life gallery space, where local and even personal politics play a large role in how it engages participants. Ono can control the colour of the scissors, the chairs, and the string, but the context of Mend is not tethered to instruction. Seated at the table, which is placed in the window outwardly facing Pender Street in the Downtown Eastside, we are compelled to ask: who is not at this table? Who is not able to begin to heal?

The Rennie Museum has addressed these concerns in its outreach programming, including scheduled visits with community groups such as Atira Women’s Resource Society as well as local public schools. Still, it will be difficult for Rennie to avoid criticism of community displacement when the installation so directly acknowledges it. But it is perhaps this deliberate choice that is the experience’s most compelling feature. Lingering over espresso (as provided in Ono’s directions for Mend), visitors will be confronted with a refurbished cup and a much larger task ahead of them. As Ono instructs to her participants: “Mend with wisdom, mend with love. It will mend the earth at the same time.” It’s a sentiment so sincere, you can’t help but try to believe it.