After studying textile art in college, Charllotte Kwon was looking for a way to expand her practice. She came to the idea of travelling abroad, so her work could be informed by the methods and applications of other cultures. This personal and historical pursuit brought her to India, where her eyes were opened to a whole new range of exquisite craftspeople. “I met incredibly creative people that had difficulty getting their work to the right audience, so I changed things,” she explains. The shift she enacted took shape in the form of a little shop on Granville Island, where imported textiles from these skilled craftspeople could finally reach the right audience. That initial push for change within the textile industry in East Asia happened roughly 30 years ago; since then, Kwon’s company Maiwa Handprints has expanded into three retail locations across the Lower Mainland; taken on the task of educating a new generation on the importance of natural dyeing, weaving, and other forms of textile art; and created a sister foundation providing micro-grants to artisans unable to purchase the necessary tools required to run their businesses.

From behind her desk above the flagship Maiwa store, surrounded by reclaimed wooden closets filled with ancient textiles, Kwon seems flippant about her past successes, and incredibly focused on her original vision of a changed future. “There’s a real problem, where exquisite artisans who set the benchmark for craft within their culture have trouble selling their work locally, because of the low price point of tourist art and mass-produced craft,” says Kwon. Where this gap exists in the marketability of high quality crafts in India, Maiwa looks to build a bridge—a bridge making it possible for Indian artisans to fairly sell their goods in parts of the world where demand is strong. “The idea is that we work with artisans, give them that leg up, those pillars of business, and then they go on to find other people to trade with. We give them that solid support, teaching them the costing, quality control, and so forth,” explains Kwon. “We don’t want them to only have Maiwa, because it’s a bit of a worry that if something were to happen to us they would be dependent. We don’t want them to be dependent. The whole idea is for them to be empowered. That’s part of the training and the building of the products, is that they learn how to sell globally.”

Having been an advocate for the preservation of knowledge surrounding plant dyes since the early ‘80s, Kwon believes the tides are just now turning back in the direction of more traditional methods. “I think now the public is ready. Just like with slow foods or organic foods, people are starting to be more critical of the fashion industry’s footprint,” she says. “There’s been much more interest in research, talking to farmers, and getting people to grow dyes again lately—it’s really exciting.” Plant-based dyes, she argues, are a “no-brainer” when it comes to seeking out conscious clothing.

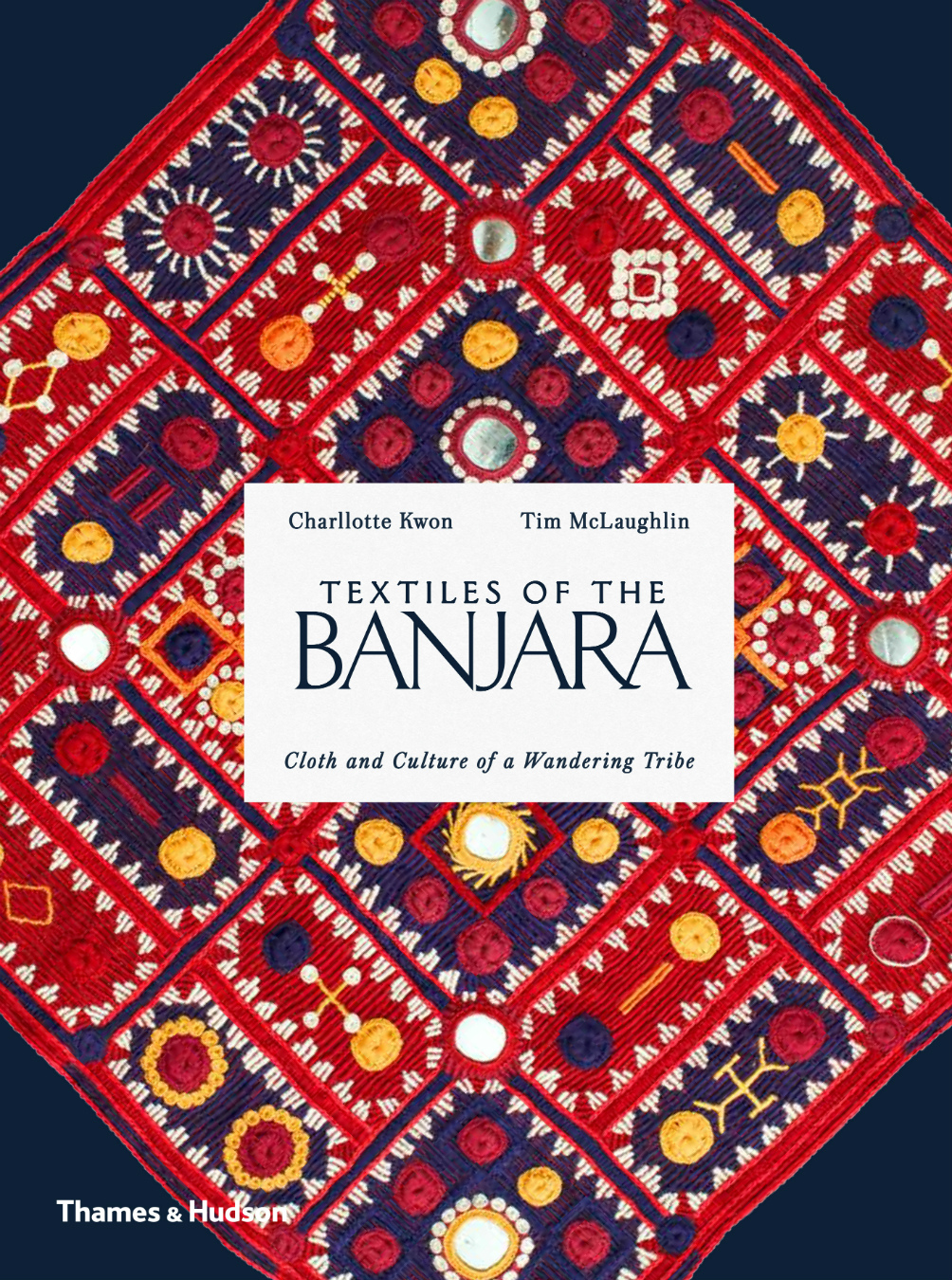

Eager to educate the public on the history of Indian artisans, Kwon and photographer Tim McLaughlin recently published a book with Thames and Hudson on the subject. Textiles of the Banjara archives traditional patterns of the Banjara people; in doing so, Kwon hopes to bring awareness to the traditional significance of patterns used when making textile art. It helps us to understand and be more sensitive when designing things ourselves, she says. “We need to know what the history is—why they made these designs, why they aren’t floral, for instance, or why they used certain stitches—so we can ensure the languages of the stitches stay within that culture,” she explains. “That’s the difference between labour and art.”

It’s not often you find a retail store that puts such a premium on this variance. Maiwa is more than just a store, though—beyond scarves and blankets, Kwon is in the business of selling stories, and selling pieces of art that are labours of love, not labours of necessity. Each dye pattern or set of stitching is its own dialect; the textile pieces are statements from the hands of their makers. The items sold at Maiwa are love letters written in cotton or sealed with indigo, while Kwon and her team take the role of the postman, delivering each precious message faithfully to the homes of those ready and eager to listen.

_________

On the go? Sign up for our newsletter and get stories delivered right to your inbox.