Four crews lined up in order on the Seine River for the finals. The event was the men’s four without coxswain. The British boat was crewed by oarsmen from Trinity College, Cambridge. The Swiss were European champions. The French were hometown favourites, cheered on by Parisians and their fellow countrymen. The fourth boat held four young men from Vancouver who had journeyed across a continent and an ocean to compete at the 1924 Olympics.

The Canadians drew the outside lane on the Seine at Argenteuil. The blowing wind made it difficult for them to hear the starter’s call: “Êtes-vous prêts? Partez!”

Three boats surged ahead, leaving the Canadians in last place.

One hundred years ago, the performance of four unheralded oarsmen from the Vancouver Rowing Club had a profound impact on sports in the city. That they did so—spoiler alert—without winning made their accomplishment the more remarkable.

In May 1924, the Canadian Olympic Committee invited the four to represent the Dominion at the Paris Olympics, much to the dismay of the rival Toronto Argonauts rowing club. But there was a catch. They had to pay their own way.

Col. Victor Spencer came to the rescue. The president of the rowing club was also one of British Columbia’s most successful businessmen. The 10th child of the founder of the David Spencer chain of department stores, he took up ranching as part of a government homesteading project after serving in the Boer War, eventually owning five ranches in the British Columbia Interior. He later served as an executive in the family business while also accumulating holdings in mining and shipbuilding. He reenlisted after the Great War erupted in 1914, rising in rank to lieutenant-colonel, carrying the title “Colonel” like a first name for the rest of his life.

Colonel Spencer and others began approaching well-heeled citizens for funds, while the amateur crew continued training daily in Coal Harbour. In less than a week, about $6,000 was raised for the trip.

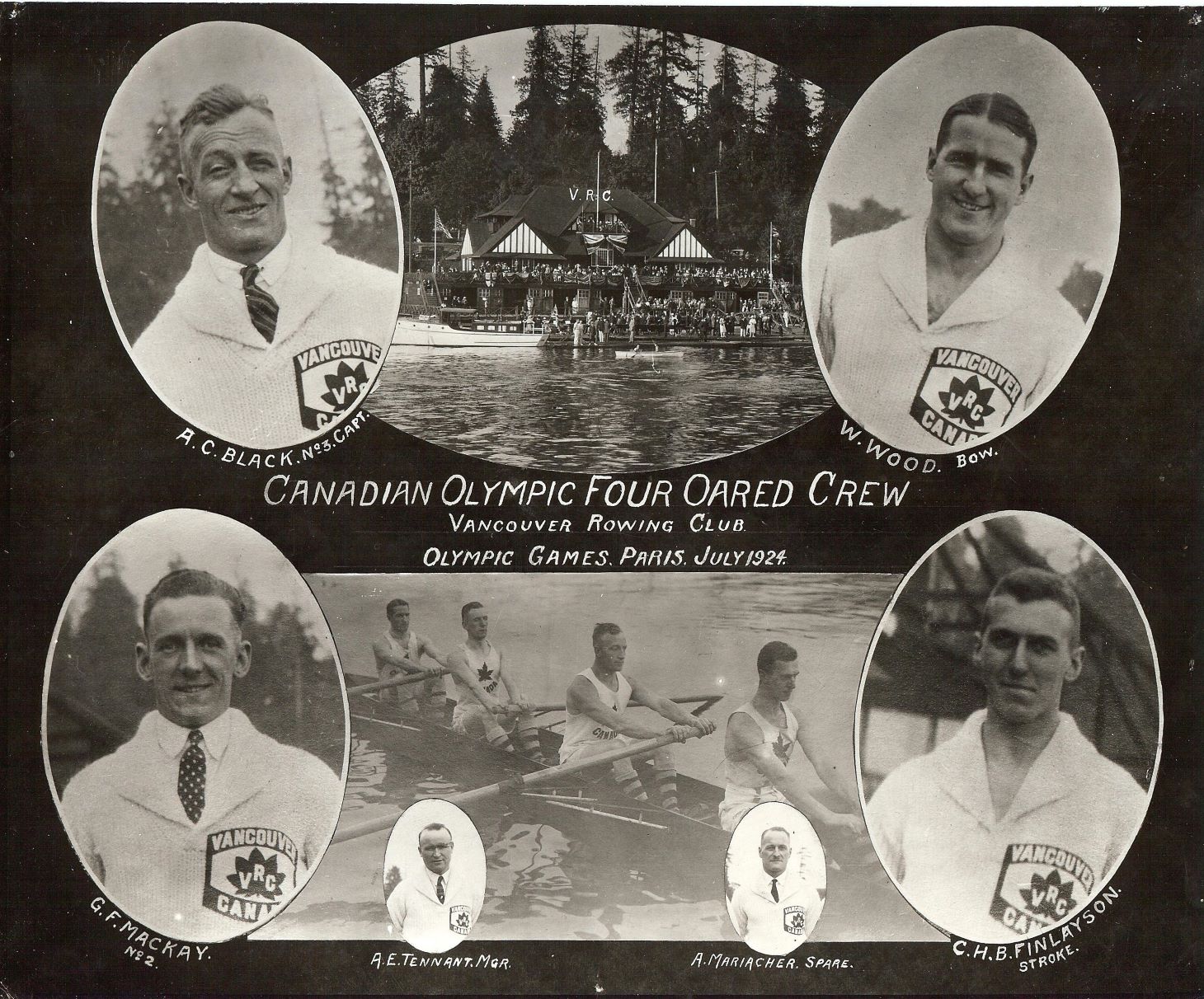

After a final Sunday morning workout, the crew—Archie Blake, George Mackay, Bill Wood, Alphonse (Alf) Mariacher, spare Colin Finlayson, and manager A.E. (Bert) Tennant—stood in a reception line in the crowded clubhouse to shake hands with visitors, including Gen. A.D. McRae, who donated their shell—the long, light boat used for racing. The club’s ladies’ auxiliary served tea. Each of the rowers was presented a nosegay, while the manager’s wife gave them a miniature totem pole as a good-luck mascot. After the reception, several hundred accompanied them to the Canadian Pacific depot where they caught the eastbound train at 5 p.m. on June 15.

After the long ride, they trained in Montreal at the Lachine Rowing Club before boarding RMS Montclare with the other Canadian Olympians. Spectators cheered from the docks as the ship’s orchestra performed. To stay sharp, the rowers exercised during the long voyage but were of course unable to practise rowing. After landing in Liverpool, they immediately departed for Southampton to catch another ship to Le Havre.

Meanwhile, French customs officials at Cherbourg inexplicably held onto their 42-foot (12.8-metre) shell. When it was at last released, it was found to have two cracks above the waterline. These were repaired, and the quartet was soon training in it on the Seine.

Photo courtesy of the BC Sports Hall of Fame.

The four were originally housed in a Paris hotel arranged by the Olympic committee. They soon tired of the daily journey to the rowing basin, leasing quarters across the street from the Asnieres Rowing Club.

A reception was held at the Continental Hotel, where the rowers were personally introduced to the Prince of Wales, the future King Edward VIII, later known as the Duke of Windsor after his abdication.

In Paris, the Canadians made a switch in the boat. Mariacher was out. Finlayson was stroke, Black the No. 3, Mackay the No. 2, and Wood in the bow.

The Canadians were given little chance of winning a medal, so their success in a preliminary heat over Argentina, the Netherlands, and especially the vaunted Swiss shocked the rowing world. In the same heat, they also set a world record time of six minutes, 30 seconds.

The day of the final race was gloomy and rainy, much like the weather during the opening ceremonies of 2024’s Olympics. The rowing course also had an oddity in that it was not precisely straight, causing the Canadians in the outside lane to stiffen their stroke on the offside.

“We were unfortunate in drawing the bad side of the river,” Finlayson later wrote, “there being a large bend we had to dodge, in addition to which there was a strong wind blowing, and the course looked and felt like the Atlantic in a hurricane.”

The Canadians made up for their poor start and were in second place at the quarter mark. At the 1,000-metre midway mark, the four trailed the English by half a length. Increasing their pace, the Canadians caught up to the leaders at 1,500 metres, only to flag at the end as the steady, disciplined, and experienced English boat crossed the finish line a length and a half ahead.

The English finished in seven minutes, eight and three-fifths seconds with the Canadians less than five seconds behind. The Swiss were four lengths behind the Canadians and the French a further two lengths behind the Swiss. A Canadian Press dispatch described the Canadian effort as a “plucky exhibition.”

After the race, manager Tennant sent a telegram to Spencer: “SECOND TO ENGLAND. ONE LENGTH BEHIND. GREAT RACE.”

The news delighted their sponsor.

“To think that from this corner of the world we could send a team that would row only one length behind the British, who proved themselves the best in the world, is an attainment that we can well feel proud about,” Spencer told the Province newspaper. “Our men have thoroughly justified the effort we made to send them there. They have upheld the honour of Vancouver in splendid style.”

The four finished the Olympics with a silver medal and a world record.

After three weeks in France and a fortnight in Britain, during which they visited the British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park in London, the team began the long journey home. Wood made a side trip to Detroit to get married, while the others arrived in Vancouver on August 16.

A large crowd greeted them at the train station, including the mayor, the police chief, aldermen, and of course, Col. Spencer. Rowing coach and banker Maj. S.C. (Bimbo) Sweeny hoisted crewman Black onto his shoulders, and soon all the oarsmen were being held aloft.

“Hail, Hail, the Gang’s All Here” was performed by the band from the Dramatic Order of the Knights of Khorassan from the local Knights of Pythias temple. A large drum major led the band and two others in full regalia on a parade to the Hotel Vancouver. The musicians were followed by a truck carrying a rowing shell and private vehicles with the rowers, their families and friends and supporters.

Later in the week, the rowers were feted at a reception at the hotel during which they were presented with inscribed gold medals. Wearing their official Olympic dress uniform of cream flannel trousers and blazers trimmed in blue, the athletes received a tumultuous ovation.

The four were the first all-British Columbian team to win an Olympic medal.

“We have had a wonderful trip,” crew captain Archie Black declared, “and our only regret is that there was that little length between our nose and theirs in the final.”

The parade they got on their arrival was the largest in the city to that time. The grand civic event was a precursor to later mass parades held for two-time gold medal sprinter Percy Williams four years later, and another for world welterweight boxing champion Jimmy (Baby Face) McLarnin in 1933.

The silver medallists also began a distinguished tradition for British Columbia rowers at the Olympics. The province has produced dozens of medallists, notable among them the late Kathleen Heddle.

In this summer’s Olympics, the rowing events are taking place at the Vaires-sur-Marne Nautical Stadium, which is about 23 kilometres east of Paris and 14 kilometres west of Disneyland Paris. The Canadian women’s eight boat includes Caileigh Filmer of Victoria and Avalon Wasteneys of Campbell River. The latter won a gold medal with the eights at the Tokyo Olympics, delayed by the global pandemic until 2021. With luck, they will race across the waters of the Bassin de Champfleuri in the finals on August 3.