Had he kept his birth name, William Alexander Smith would be remembered only by students of history.

Smith dragged British Columbia into Confederation after negotiating a dry-dock and a transcontinental railway terminus for the province. He served as our second premier while also sitting in the House of Commons.

As a writer, he wielded a ferocious pen, attacking the early colonial administration, insisting on a government of elected representatives, and demanding public nondenominational schools. He was a grocery clerk turned gold miner turned mining speculator turned photographer turned newspaper publisher turned politician, who is remembered for legally changing his name to Amor De Cosmos.

If he is remembered at all, it is as a kook. Just look at his name. Amor De Cosmos.

Behind the name is, of course, a story.

Born into a Loyalist family in Windsor, Nova Scotia, young Smith got an education in Halifax while working as a grocery clerk. The lure of riches to be found in the California goldfields led him on an arduous overland trek across the continent in 1852. Bad weather, slow progress on wagon roads, and the threat of attack by Indigenous people protecting their land forced him to winter in Salt Lake City. He set out for California on his own the following spring, a risky journey not eased by his insistence on hauling bulky photographic equipment.

The miners thrilled at being able to purchase a souvenir of working their claims in a far-off land. Business was good and Smith learned a fortune was to be made not so much from gold but in supplying and servicing others with gold fever.

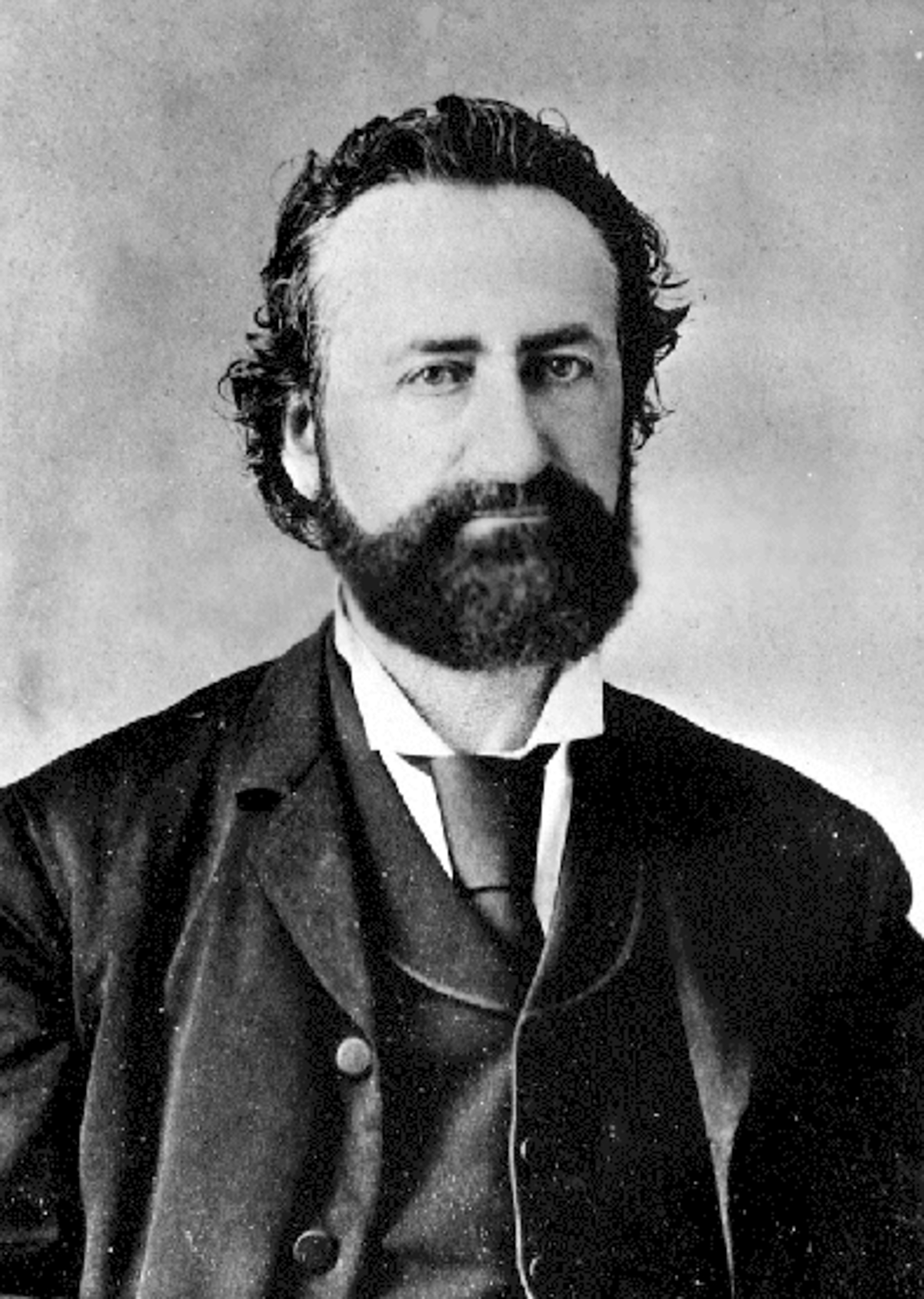

Amor De Cosmos, September 1874. Library and Archives Canada.

While staying at a mining camp and stagecoach crossroads called Mud Springs, later known as El Dorado, Smith turned out to be one of several men of similar name. He became angered when his private mail was read by others and frustrated in not knowing if he received all correspondence addressed to him. The state legislature was petitioned for a name change.

Some assemblymen objected to the “De” in his chosen moniker, thinking it an attempt to adopt an aristocratic-sounding name. A letter from Smith was read aloud: “I desire not to adopt the name of Amor De Cosmos because it smacks of a foreign title, but because it is an unusual name and its meaning tells what I love most, viz: Love of order, beauty, the world, the universe.” The legislature voted 41-20 to accept the name change. For a time, he replaced the small “e” with the Greek letter epsilon.

The news of gold found in the gravel banks of the Fraser River caused a sensation in California. De Cosmos joined his older brother, a builder, in Victoria in June 1858. On December 11 of that year, he published the first edition of the British Colonist, a weekly. (It is still published today as the Times Colonist.) The inaugural edition included a blistering attack on Governor James Douglas and the moneyed elites the publisher would oppose all his life.

Though he sold the newspaper after a few years, its appearance marked the start of a quarter-century in which De Cosmos was a central figure in the political life of the province.

De Cosmos is credited as the first to publicly call for a federation of all the scattered British North American colonies—Newfoundland, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Canada, British Columbia and Vancouver Island. He led the way in calling for a uniting of the latter two, which happened in 1866, a year before Confederation, and he was a key figure in the united British Columbian colony becoming Canada’s sixth province in 1871, a sesquicentennial to be marked next year.

His own business enterprises were less fruitful. He operated a sawmill, a quartz mine, and a cattle farm while speculating in the land boom, owning many heavily mortgaged properties throughout a colony in which a crossroads might become a boom town overnight only to revert to a ghost town soon after.

After selling the Colonist, De Cosmos launched another newspaper, the Victoria Daily Standard. He also promoted the failed Victoria, Saanich & New Westminster Railway Co., which was to be a train and ferry service between the capital and the mainland, from Swartz Bay to Steveston by boat, promising to reduce the time of the journey to two hours, 35 minutes.

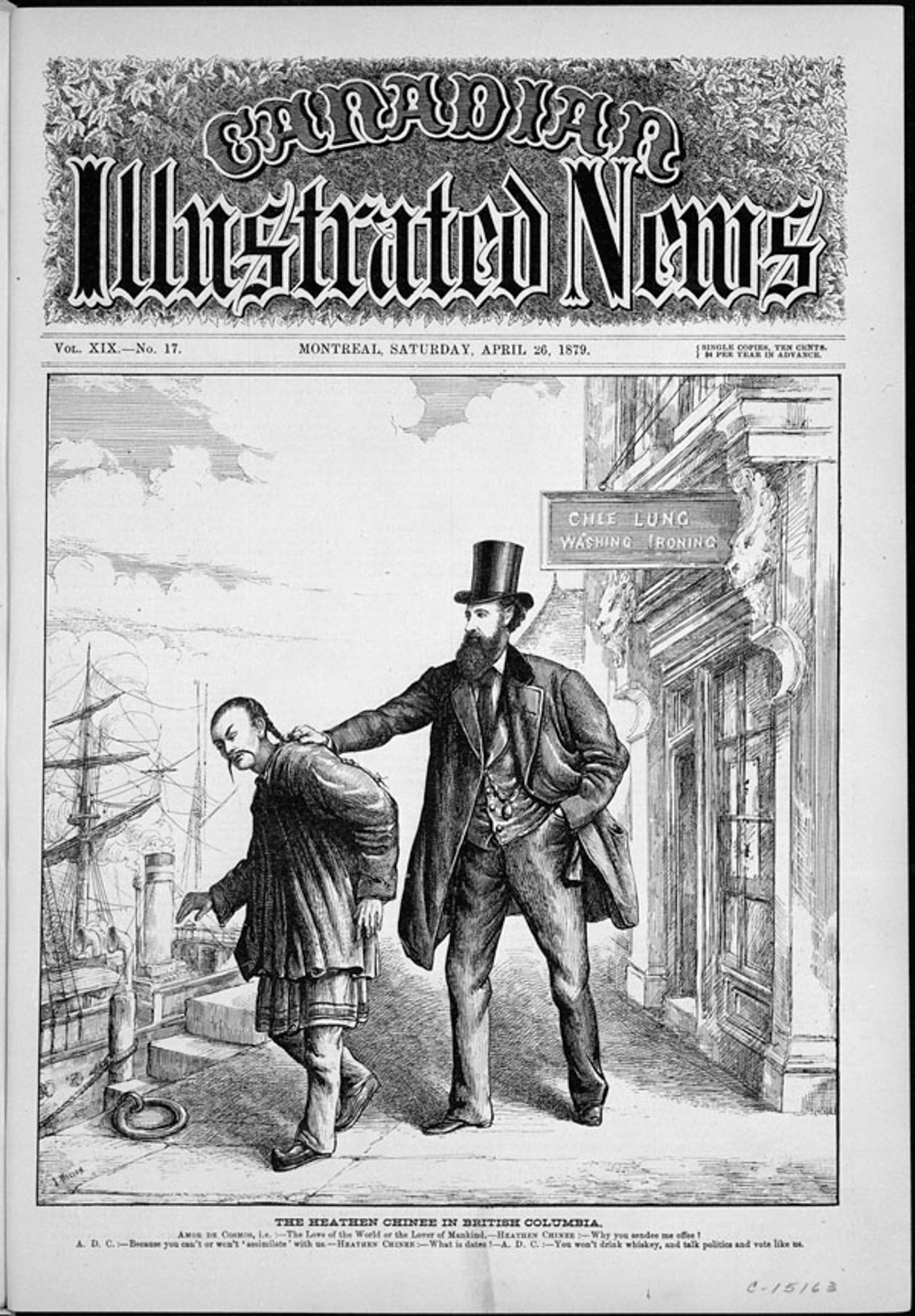

De Cosmos’s attitudes were typically colonialist. The land and its resources were to be exploited by men of action, such as himself. The Indigenous peoples on whose land he made that money, he treated with a paternalistic arrogance, at best, and his disdain for the Chinese community was bigoted even for his era.

A racist depiction of De Cosmos ejecting a Chinese man from Canada for failing to integrate, from the Canadian Illustrated News, 1879. Library and Archives Canada.

Even as he willed the colony into joining Canada, he predicted a troubled union. “I would not object to a little revolution now and again in British Columbia, after Confederation, if we were treated unfairly,” he said in 1870, “for I am one of those who believe that political hatreds attest the vitality of a State.”

In time, he would call for his province to leave Canada, an odd position for someone considered one of the Fathers of Confederation.

Pugnacious in print, assertive in person, De Cosmos’s behaviour became more erratic and eccentric as he aged. He cried during speeches and he had fistfights on the street. It was said he so feared electricity he not only refused to have it in his home but would not board streetcars after electricity replaced horses.

He was declared insane and spent his final months as a recluse in his brother’s home. He died on July 4, 1897, at the age of 71. He never married.

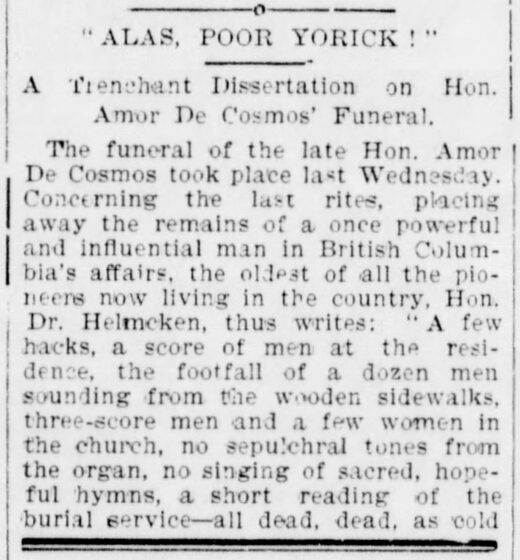

Only about 60 men and a few women attended his funeral, fewer still appearing at Ross Bay Cemetery for his burial. That a man once hailed as a hero and a patriot would get so little recognition distressed his contemporary, Dr. John Sebastian Helmcken, who wrote a letter to a Vancouver newspaper.

“Such a funeral is neither worth living, nor dying for,” Helmcken wrote. “Is honour and glory, then, a mere temporary public gaseous emanation, like the will-o’-the-wisp, leaving no trace behind, only beautiful and deluding while it lasts?”

Dr. Helmcken’s letter on De Cosmos’ funeral. Vancouver Daily World, July 10, 1897.

His old newspaper, the Colonist, editorialized the passing of the “picturesque figure” by noting “his zeal greatly outran his discretion.” His possessions were sold off in a public auction a month after his death.

The establishment figures he tweaked all his life got their vengeance on his passing. Streets were not named for him. In 1973, the city archivist suggested naming after him a new street ending at the building housing the newspaper he founded. It didn’t happen.

A five-storey building now rests on the site of his final residence, just west of Central Middle School, uphill from downtown Victoria. The developer named the building Amour De Cosmos Apartments, misspelling the first name.

To pay homage to De Cosmos today, one can read a plaque in Bastion Square, or, better, visit Ross Bay Cemetery, where he has a fine monument: “A faithful servant of the people, now at rest.”

Read more local history stories.