A sailing ship approached Victoria Harbour as the sun set on September 18, 1860. The hold contained 15 tons of sugar, a valuable commodity for a settlement supplying prospectors with gold fever. The ship caused a kerfuffle, though more because of its passengers than its cargo. It was flying the royal standard of Hawai’i.

The following day’s British Colonist newspaper described the scene. “Yesterday evening one of the most beautiful little schooners eye ever beheld, sailed into our harbour, and anchored off Laurel Point,” it reported. “She proved to be the Emma Rooke, 19 days from Honolulu, and her arrival created some little excitement, as soon as it became known that Prince Lot Kamehameha, of the Sandwich Islands” was aboard.

The colony had been forewarned just a few hours earlier to expect the Prince, brother of Hawaiian King Kamehameha IV. The Colonist had set the news in type but had yet to publish. Once he heard of the yacht’s arrival, Henry Rhodes, a local businessman named consul on behalf of Hawai’i the previous year, rushed out to board the vessel.

The Prince was the first foreign royal to visit what is now British Columbia. A member of the British Royal Family wouldn’t visit until 1882, when the Marquess of Lorne toured the country as Governor General with his wife, Princess Louise, daughter of the queen for whom the city of Victoria is named.

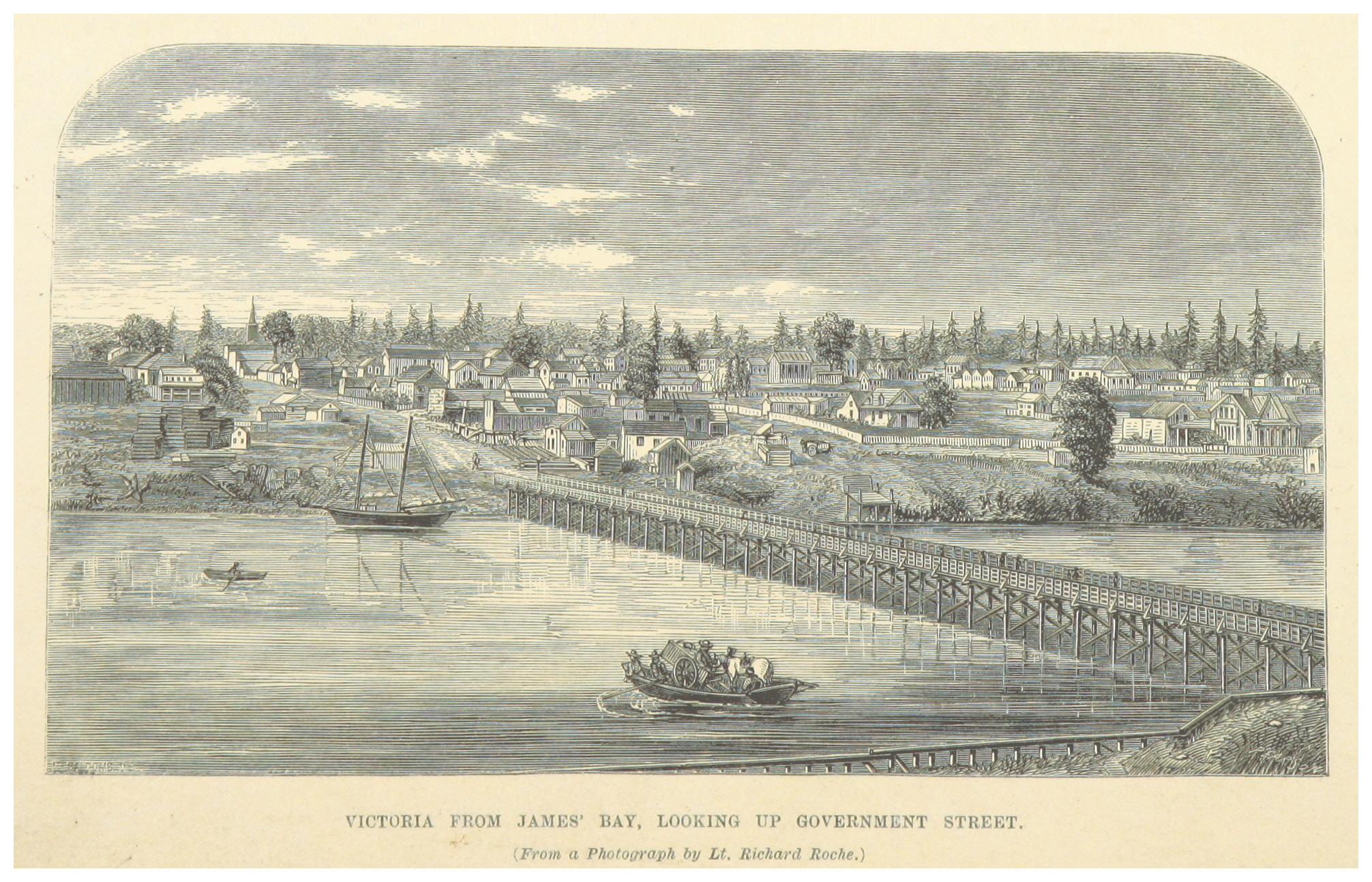

Two years earlier, the sleepy village of 300 mostly white people surrounding a Hudson’s Bay Company trading fort had boomed overnight. Fortune seekers making their way to the gold fields along the Fraser River travelled through Victoria, where they stocked up on supplies. About 30,000 passed through the area in 1858 alone. By the time the schooner anchored, the settlement’s permanent population was at least 3,000.

Victoria was still two years away from incorporating as a city. After that, four more years would pass before the Colony of Vancouver Island merged with the Colony of British Columbia, and it wouldn’t join Confederation as the westernmost province of Canada until 1871.

The rough-and-tumble settlement had more saloons than churches. The Victoria the Prince visited in 1860 was more Deadwood than Downton Abbey.

He brought a letter of greeting that listed his formal titles as “Prince General Kamehameha, Commander-in-Chief under the King, member of his Privy Council of State and the House of Nobles, and Minister of the Islands.”

A bout of congestive fever had left the Prince feeling sickly with liver ailments. A sea voyage was prescribed as a cure. He and his entourage had set sail from Honolulu at the end of August with a final destination of San Francisco, which he had first visited in 1849.

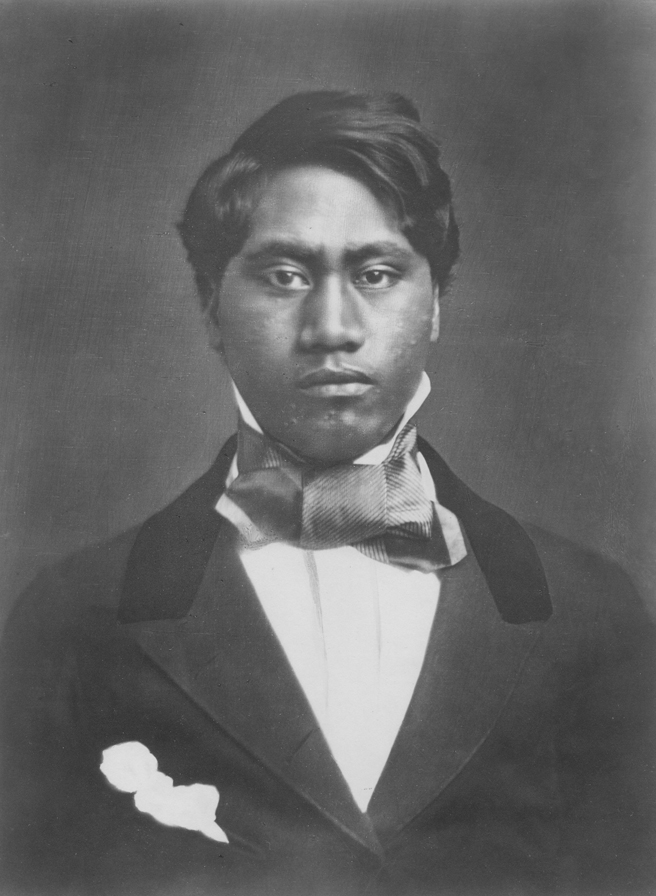

The 29-year-old Prince was a stout man, who caused a stir when he promenaded with his entourage along Yates Street. He dressed in what locals presumed to be the latest English fashions, including a thick overcoat, patent leather boots, and a heavy chain attached to a gold watch. He sometimes stood with his hands half-stuffed into pockets, a boyish casualness that likely put others at ease. On his head he liked to wear a plaid jockey cap at a jaunty angle.

The Prince was accompanied by his father, Mataio Kekūanāo‘a, governor of the island of Oahu, whose other surviving son was King; David Kalākaua, son of a high chief; Levi Haalelea, like Kalākaua a member of the house of nobles and the King’s Privy Council; and Josiah Chapman Spalding, an officer in the Hawaiian army who served as the Prince’s aide-de-camp.The 156-ton yacht, named after the Hawaiian queen, was serviced by five Hawaiian seamen, who were hired at $15 per month with a $15 advance.

Victoria in 1862, by Charles Edward Barrett Lennard. Photographed by Richard Roche, courtesy of the British Library.

Quarters were secured for the royal party at the Hotel de France, the finest in the city, a two-storey wood building on the east side of Government Street, now the site of the Bay Centre mall. The hotel was home to such prominent citizens as Captain George T. Gordon, former commanding officer of HMS Cormorant, a six-gun paddle sloop that was the first steam-powered British warship in the Strait of Georgia, and Chartres Brew, a justice of the peace and the chief inspector of police for the colony at £500 per annum (about $110,000 in today’s dollars).

The hotel was owned by Pierre Manciet, a San Francisco hotelier and restaurateur who had lost his right arm when a cannon prematurely fired as part of a salute in honour of the inauguration of the French Hospital in that city. He became its first emergency patient. (That sad fate was still better than what awaited his son, who would be shot to death in a saloon brawl over a game of stud poker in which he had not taken part.)

It is unknown if the Prince’s royal standard flew above the hotel during his stay, as it would later in San Francisco.

“Owing to the delicate state of the prince’s health he has not been much in public,” the Colonist reported. “Yesterday, however, accompanied by his suite, he paid a visit to Beacon Hill and the environs of the town. Although laboring under indisposition, and necessarily somewhat secluded, the prince has received many calls from our prominent citizens.”

James Douglas, the colony’s governor, was away from Victoria, so it fell to the Colonial Secretary and the Chief Justice to welcome the Prince at the hotel. He was also called on by a warship captain and the Anglican Bishop of Columbia, as well as the Speaker and numerous legislators.

In an age where racial supremacy and bloodlines dominated discourse, the Prince’s dark complexion, often described as mahogany, and noble ancestry presented a challenge to social discussion among the upper class.

The prince later took the throne of Hawai’i as King Kamehameha V. Photo by Charles L. Weed, 1865.

“We trust our citizens will not be backward in showing the degree of courtesy to those distinguished strangers which their position warrants,” the Colonist urged. “Every year will increase the commercial intercourse between the colony and the Hawaiian kingdom; and no means should be allowed to slip by which we may cultivate friendly relations with a people whose government is patterned after ours, and whose prosperity cannot but enhance our own.”

The Colony of Vancouver Island imported molasses and sugar in half-barrels from Hawai’i, as well as pulu, the yellowish-brown vegetable wool harvested from young fronds of tree ferns. The silky material was used in mattresses and upholstered furniture. “It is universally considered to be equal to feathers, and better than curled hair, for this climate, at half the price of either,” claimed an advertisement for Pierce and Seymour furniture dealers. A letter could be sent from the colony to the islands for one cent.

On his fourth full day in the colony, the Prince rode over to Esquimalt and visited HMS Topaze, “where he was received in the most courteous manner, with manned yards and royal salutes on arrival and at parting, and with a superb collation on board,” The Polynesian newspaper of Honolulu would later publish from a private correspondence. “On returning, H.R.H. called upon the family of Governor Douglas. Yesterday, Sunday, service was held on board the Emma Rooke, the Rev. Mr. Kaulehelehe officiating, some twenty Hawaiian families resident in Victoria attending, to whom the prince made a short address exhorting them to lead an orderly and industrious life in this foreign land, and by so doing acquire the means of returning to the land of their birth and leave a good name behind them.”

The local Hawaiians, who called themselves Kanakas, had a history in British Columbia from the fur trade with later work as farmers, labourers, and longshoremen. A prominent descendant was Mel Couvelier, a businessman who owned a poultry processor and a haberdashery before serving as mayor of Saanich from 1977 to 1886, when he became the province’s finance minister.

Victoria, the Prince later said, reminded him “very strongly of San Francisco at the time of his visit in 1849.”

After six days, the Hawaiians set sail for California. They did so without three of the original crew, as Aikanai, Kapahu, and Kaliai are thought to have deserted, likely lured to the gold fields.

The schooner’s 19-day voyage from Hawaii to Victoria held a speed record for many years after. The Emma Rooke remained in service as a cargo vessel until running ashore on the northern point of Big Island in 1864. All crew, passengers and animals were saved, though the cargo was lost.

In 1863, Prince Lot ascended to the Hawaiian throne after the death of his younger brother. He took the name Kamehameha V. He rejected his brother’s liberal reforms, writing and promulgating his own constitution, and permitted the importation of Japanese labourers to the islands.

The King grew obese at 170 kilograms (375 pounds), which confined him to the palace. In his final days, he was unable to stand or support himself, and he died December 11, 1872, his 42nd birthday. He had never married, and so with him died the Kamehameha dynasty.

The legislature selected hiss cousin William Lunalilo over David Kalākaua as king, only for Lunalilo to die the following year. It then chose Kalākaua, who embarked on a famous world tour in 1881, becoming the first reigning monarch to visit the United States and for whom the first state dinner was held at the White House.

King Kalākaua gave the United States exclusive right to Pearl Harbor as a naval base. He died at age 54 in 1891 and was replaced on the throne by his sister, Queen Liliʻuokalani, who sought to restore the monarchy’s power. Her efforts led to her being overthrown by American businessmen, who declared Hawaii a republic before it was annexed by the United States. She served as the only queen and final monarch of the Hawaiian royal house. Her brother, one of two future monarchs to visit British Columbia aboard the Emma Rooke, was the last king.

The royal house’s close ties to Britain can be seen to this day. Captain George Vancouver had presented King Kamehameha I with a Union Jack as a gift of friendship from George III. That symbol was eventually incorporated into the Hawaiian flag and remains there to this day in the upper left corner.

Read more local History stories.