Even though it has been one of Vancouver’s most iconic structures for nearly nine decades, the Burrard Street Bridge still has its share of little secrets.

As local artists Josh Hite and Scott Billings discovered while putting together an art project back in 2011, the structure is actually rife with hidden nooks and crannies—including a stairwell on the south side, sealed off virtually since the day it opened in the summer of 1932.

“We haven’t been able to find any historical photos, but we’ve seen the original drawings,” Billings says. “There were tread-plates on every single stair, there were bronze railings, and then the light-fixtures.”

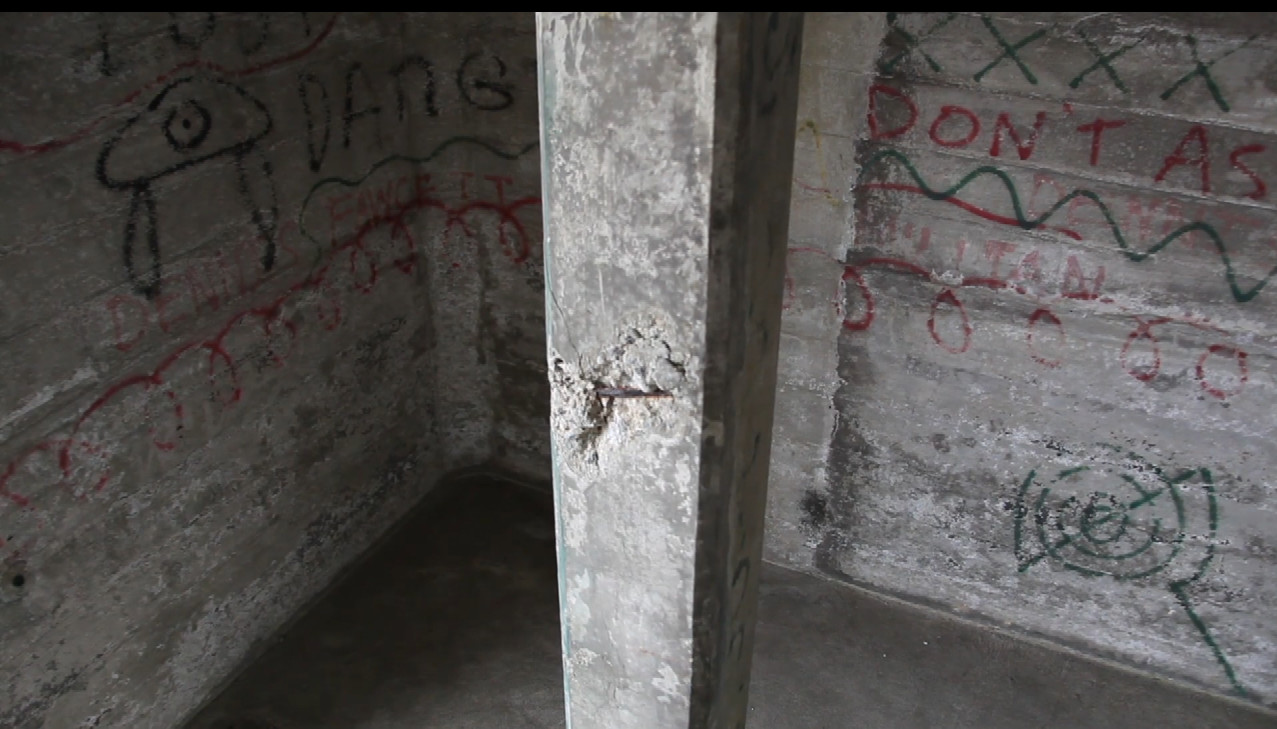

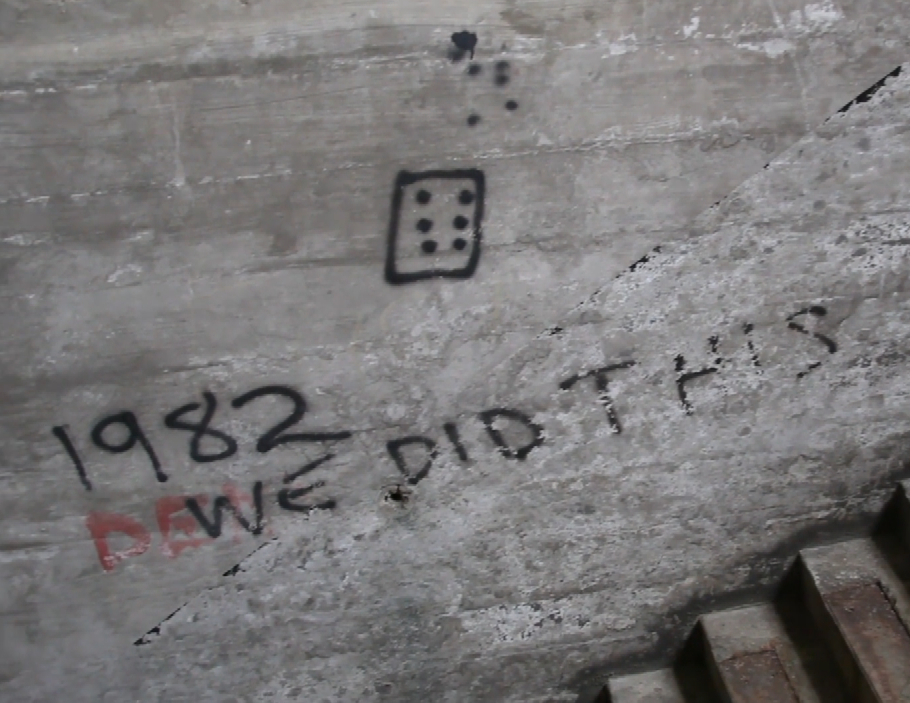

Today, that same stairwell, which once connected the bridge deck with Vanier Park, retains none of its former grandeur. Instead, it’s merely 70-odd feet of cold concrete, beset by high winds and the constant ka-thunk of cars overhead, its walls layered with decades-old graffiti.

The stairwell’s top entrance is still accessible for those who know how (Billings and Hite, who spent 22 days inside back in 2011, remain mum about exactly how), but the door at the bottom was bricked-in long ago.

The bricked-in entrance to the stairwell from ground level. Still from Stairwell 2016 by Josh Hite and Scott Billings.

Despite their extensive research, Billings and Hite were unable to find out exactly why the stairwell was sealed off, although it’s well known that it wasn’t long before the enclosed space—constructed at the height of the Great Depression—was plundered by thieves.

“We researched the hell out of why it was closed,” Billings adds. “We went to the archives, hit up the microfiche to see if we could determine why. But we still don’t really know…

“We don’t know if a major altercation took place in there to initiate the closure. What we do know is that everything inside got ripped off pretty quick—all the bronze for the railings and all the light fixtures.”

Constructed between 1930 and 1932, the Burrard Street Bridge had been something of a pet project for its designer, John R. Grant. Grant himself had been envisioning a crossing between downtown and Kitsilano since at least 1906, and had undertaken research of his own as early as 1910, but a series of failed civic referendums nixed the idea until the late 1920s.

“The prospect of building that bridge brought me back to Canada,” Grant told the Vancouver Sun in June 1932. “It never left my mind in all those years although other projects were conceived and completed in the meantime. Of course, the original design altered as new traffic demands became evident and from 1927 I worked almost continuously on the Burrard Bridge project.”

View of the stairwell from the top, looking down. Photo by Josh Hite and Scott Billings.

Though Grant undertook the engineering work, it was associated architects Sharp & Thompson who helped give the structure its art deco flourishes, which were further decorated by sculptor Charles Marega. And coincidentally, one of the firms that constructed the bridge was owned by one Fred Dawson (father of Graham Dawson, who would, with Jack Poole, go on to form Daon Developments, one of the city’s biggest real estate players throughout the 1970s and 80s).

Opening in July 1932—to fanfare featuring an RCAF seaplane flying under the bridge and music by the Kitsilano Boys Band—the bridge has remained a celebrated structure ever since, although it hasn’t always been a critical darling.

Not only did Grant have to defend his creation in the newspapers against a Vancouver Art School teacher who labelled it a “monstrosity,” but a string of mostly unsuccessful suicide attempts (beginning in the fall of 1933) began to bring the structure a modicum of negative publicity.

“I shouted to Pete to take him to the Georgia Towing wharf,” a tugboat attendant told the Vancouver Sun, of one such attempt in August 1950. “That’s where we always take ’em . . . They generally come through all right. I pulled out my first one 15 years ago. Since then I’ve chalked up nine and only two of ’em died.”

Graffiti adorns the walls of a stairwell landing. Still from Stairwell 2016 by Josh Hite and Scott Billings.

By the time Hite and Billings decided to pitch their project to the city of Vancouver, the bridge had already been through a major renovation. But despite some interest by the engineering firm involved, reopening and refurbishing the stairwell had never come to fruition.

“We were able to speak to one of the guys at Iredale [Architecture],” Hite notes, “who did the drawings for the renovation and heritage restoration of the Burrard Bridge, going back a few years. They had started their research around the same time as we were doing ours. So, unbeknownst to us, there was a conversation going on, and at least some of the architects were interested in reopening that stairwell.”

More graffiti inside the stairwell. Still from Stairwell 2016 by Josh Hite and Scott Billings.

Luckily, the project Hite and Billings conceived not only allowed the public access to the stairwells for the first time in decades, but also transformed the space into a full-fledged artistic experience. After building and installing a 70-foot track, the pair collected more than 24 hours of footage inside, editing it into what appears to be an hour-long tracking shot that moves repeatedly up and down the full length of the stairwell. But, as they recall, the installation was no easy task.

“We originally thought: oh, we’ll just install this thing,” Billings laughs. “Pop it up in a week. Then we can take a week off to relax. But instead we were building for 18 days straight.”

“Working with the city was the easy part,” Hite adds. “We just had to schedule it. It was actually an incredible experience. We had a hard time believing that they would let us do it. What we wanted to do was pretty ambitious, and they kept just saying yes.”

While the final result of their efforts was finally shared with the public in 2017, the Burrard Bridge stairwell has since receded into relative obscurity. Despite some discussions back in 2011, the city has currently announced no plans to reopen the stairwell. Although, as Hite notes, with the benefit of 22 straight days experience, this may not necessarily be a bad thing.

“It’s such a gorgeous, incredible space, but it’s also a pretty punishing space to be in,” he laughs. “It’s 10 degrees colder, with 20-mph winds, it’s echoey. It’s loud. It’s not very much fun to be in for long periods of time.”

Read more about Vancouver history.