It’s the most-filmed location in the Pacific Northwest, familiar to audiences the world over. It’s the laboratory where Ryan Reynolds becomes Deadpool, and the Chinese prison from which Jet Li escapes in Romeo Must Die. In the X-Files episode “Excelsis Dei,” Mulder and Scully investigate it as a haunted seniors home. Riverdale, Supernatural, and countless DC superhero shows have filmed among its weathered exteriors.

Tucked into a crescent of land in Coquitlam a quarter the size of Stanley Park, the buildings that make up Riverview Hospital—West Lawn, East Lawn, Crease Clinic—have proven irresistible to filmmakers. The crumbling red brick, paint-peeling Tuscan columns, and barred windows create an image of authority in decay. No wonder horror films, including Grave Encounters and See No Evil 2, have made use of the former institution.

But the true history of Riverview is even more compelling.

Riverview became a Hong Kong prison holding Jet Li’s character in the 2000 film Romeo Must Die.

The hilly, fertile land where Riverview is located is on the traditional territory of the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm (Kwikwetlem) First Nation, who used it as a summer camp, graveyard, and a high ground refuge when the nearby Coquitlam River would flood. In 1904, to take pressure off the crowded Provincial Hospital for the Insane in New Westminster, the B.C. Government appropriated 1,000 acres on the western bank of the river as the site for a new hospital for the mentally ill.

The upland site was cleared and an architectural competition launched to draw up plans for the new facility, the Hospital for the Mind at Mount Coquitlam Over the next five years the lowland was developed into Colony Farm, where patients would be employed growing food for the new modern asylum. Dr. Henry Esson Young, the B.C. Minister of Education, promoted the development of the grounds, which at one point were also considered as a site for the University of British Columbia.

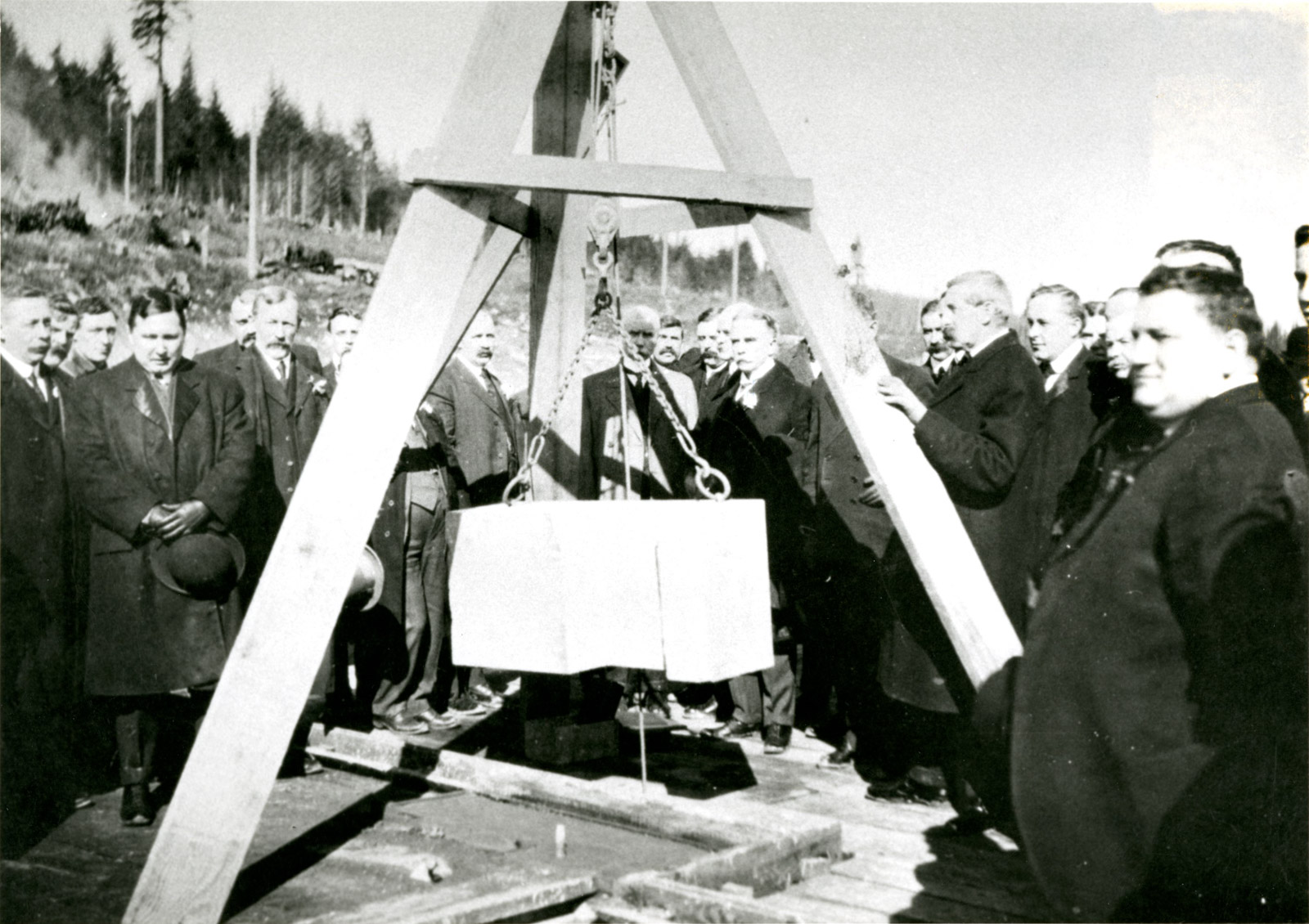

Lieutenant Governor Thomas Patterson lays first corner stone at Essondale, 1908. Image courtesy of the City of Coquitlam Archives.

According to the City of Coquitlam archives, J.C.M. Keith’s plan for the design of the hospital received the highest commendation from the New York State Lunacy Commission. Built in stages over the next decade, the structures were made of reinforced concrete with a red brick exterior. The plan called for a central administrative building flanked by domed structures, as well as separate housing for male and female patients. In 1913, the rechristened Essondale Hospital opened.

New buildings were erected on the site throughout the 20th century. The extensive botanical gardens, and nearby Colony Farm, supposedly created a pastoral setting for patient recovery. As the naturalist society of nearby Burke Mountain notes, “Riverview’s design emphasis was to create calm and opportunities for pleasant outdoor experiences… It is a place where the mind can be soothed by the sights and sounds of nature.”

The Hospital for the mind, 1912. Image courtesy of the City of Coquitlam Archives.

Riverview Reminisces, Val Adolph’s collection of oral histories from Riverview staff, sketches an efficient midcentury hospital where female orderlies followed a strict dress code and were paid $75 dollars a month, $25 less than their male colleagues. Many staff and nursing students lived on the hospital grounds in the nurses residence.

In 1940, changes to the Mental Hospitals Act started to eliminate terms such as “lunatic” from mental health jargon. Originally designed for 1,800 patients, by 1956 the buildings accommodated 4,306 patients and 2,200 staff members. One nurse recalled that there were so many beds in the North Lawn unit that to change the sheets each bed had to be rolled into the hallway. By 1965, what had been Essondale Hospital was combined with the Crease Clinic of Psychological Medicine, to be known as Riverview Hospital.

Crowding, as well as the limitations of early 20th-century medicine, was dangerous. Riverview Reminisces includes stories of patients prying the gratings off windows and threatening to jump from the roof, or harming themselves with everyday items such as pencils. Yet there are also stories of staff bringing in candles and centerpieces for Christmas dinner, observing the holidays alongside their patients.

Many procedures used at Essondale and Riverview, such as electroshock therapy, confinement, and forced sterilization, are now recognized as harmful. In 2003, the Supreme Court of B.C. rejected a lawsuit by former patients who claimed they were subjected to forced sterilization. Between 1933 and 1973, under the Sexual Sterilization Act, B.C. sterilized more than 200 women for reasons ranging from institutional convenience to low intelligence to promiscuity. In 2005, after a second suit, the government offered the nine surviving patients a cash settlement totalling $450,000.

Workers at Colony Farm, 1913. Image courtesy of the City of Coquitlam Archives.

By the 1980s, mental health priorities had changed yet again. Patient labour at Colony Farm was ended. Complaints of overcrowding began to register. A large allotment of land was sold off, without public consultation, to become a housing development. Some of the facilities, most notably West Lawn, were deemed unsafe. Throughout the nineties, many of the buildings were shuttered, one after another, and in 1995 Colony Farm became a Regional Park.

During this time the process of deinstitutionalization began to sweep the province. Mental health advocates argued that segregating the mentally ill in crowded institutions like Riverview was ineffective, if not harmful. Patients would do better remaining with their families and communities. As Diane Strindberg wrote for the Tri-City News, “Wards with fifty people and shared bathrooms are no longer considered appropriate for people with mental health concerns.” By the early 2000s there were fewer than 1,000 patients on the grounds, and in February 2012, Riverview officially closed its doors.

Nurses in front of the West Lawn Building at Essondale, 1939. Image courtesy of the City of Coquitlam Archives.

Whether deinstitutionalization was better for patients and society, and what happened to patients once Riverview closed, is still fiercely debated. Port Coquitlam MLA Mike Farnworth, interviewed for the hospital’s closing, said that de-institutionalization “has worked in many cases, and there are a lot of good aspects to it, [such as] the idea of having mental health services delivered in communities …. But at the same time … there are challenges and problems with it as well.”

Others were less politic. “Riverview Hospital is being emptied, and the sick are being thrown to the coyotes,” wrote Terry Gould in “Between Madhouse to Flophouse,” a notorious article published in Vancouver in 1992, warning that as the hospital closed its doors, former patients were ending up on the streets, frequently becoming homeless or addicted to drugs. In 2013, Canadian Press reporter Vivian Luk wrote that “An affiliated pilot project that provided supportive housing for people with mental health, addiction, and chronic diseases” was shut down at the same time Riverview closed. A move meant to return patients to their communities and loved ones was, some thought, instead putting them at risk.

While it’s true that between 1999 and 2014, Vancouver’s homeless population more than doubled, how much was due to Riverview closing rather than, say, population growth and the city’s multiple real estate crises, is difficult to say. But Gould’s sentiment was widely shared: outpatient care by its very nature placed more people with mental health issues in communities, where they could fall through the cracks.

The segue from mental hospital to movie set began during the late 1980s and early 1990s. The first significant feature to be filmed at Riverview was 1986’s The Boy Who Could Fly, directed by Nick Castle (of The Last Starfighter). The 1992 serial killer film Jennifer 8, starring Andy Garcia and Uma Thurman, made use of Riverview as a rundown sanitarium, marking the first but far from last time the hospital served as a shadowy institution. The West Lawn building can also be seen in the Adam Sandler film Happy Gilmore (1996) as the Silver Acres retirement home where Ben Stiller’s character works.

But it was the X-Files that returned time and again to Riverview, shooting 13 episodes there between 1993 and 1996, including classics such as the pilot, “Squeeze,” “Young at Heart,” and “The Calusari.” According to Michael Kennedy of Screen Rant, “The X-Files became known for its distinctive look, made possible by its Vancouver locations.” The Chive calls Riverview as “perhaps one of the most versatile shooting locations on the show,” and the Crease Clinic features prominently in many exterior shots. The X-Files: I Want to Believe (2008) and the two reunion seasons also filmed on the hospital grounds—only now, they were competing with other productions.

Riverview as a haunted convalescent home in the X-Files episode “Excelsis Dei.”

According to the Internet Movie Database, 181 titles list “Riverview Hospital” as a filming location. Horror movies including Jennifer’s Body, Halloween Resurrection, Final Destination 2 and the Grave Encounters series have employed the West Lawn and Crease Clinic buildings as exteriors, and Riverview has long been a featured location on shows such as Supernatural, Arrow, Smallville, and Psych. In fact, according to ComicBook.com, a “haunted asylum” episode of Psych was inspired by Riverview’s history.

In 2018, the Riverview grounds were fully booked, with 200 film and TV contracts for the last fiscal year, and as many as five productions using the hospital grounds at the same time. “It’s the most popular filming location in Canada outside of a studio,” Brenda Rattienbury, film and special events manager for BC Housing, told the Tri-City News.

In 2021, as part of the ongoing process of decolonization and reconciliation, the Riverview lands were given the traditional name səmiq̓wəʔelə (Suh-MEE-kwuh-EL-uh) meaning “place of the great blue heron,” in recognition of the Indigenous rights and title to the land of the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm First Nation. BC Housing and the kʷikʷəƛ̓əm people are currently developing the Riverview lands into mixed-use district—a “complete community”—with employment opportunities and a range of housing options. A new addiction treatment centre and a mental wellness facility have been constructed. Meanwhile, filming continues.

This new chapter seems to acknowledge all stages of Riverview’s history: Indigenous territory, centre for mental wellness, in-demand film location, and residence. The dark secrets of Riverview may have finally been put to rest.

Read more local history stories.