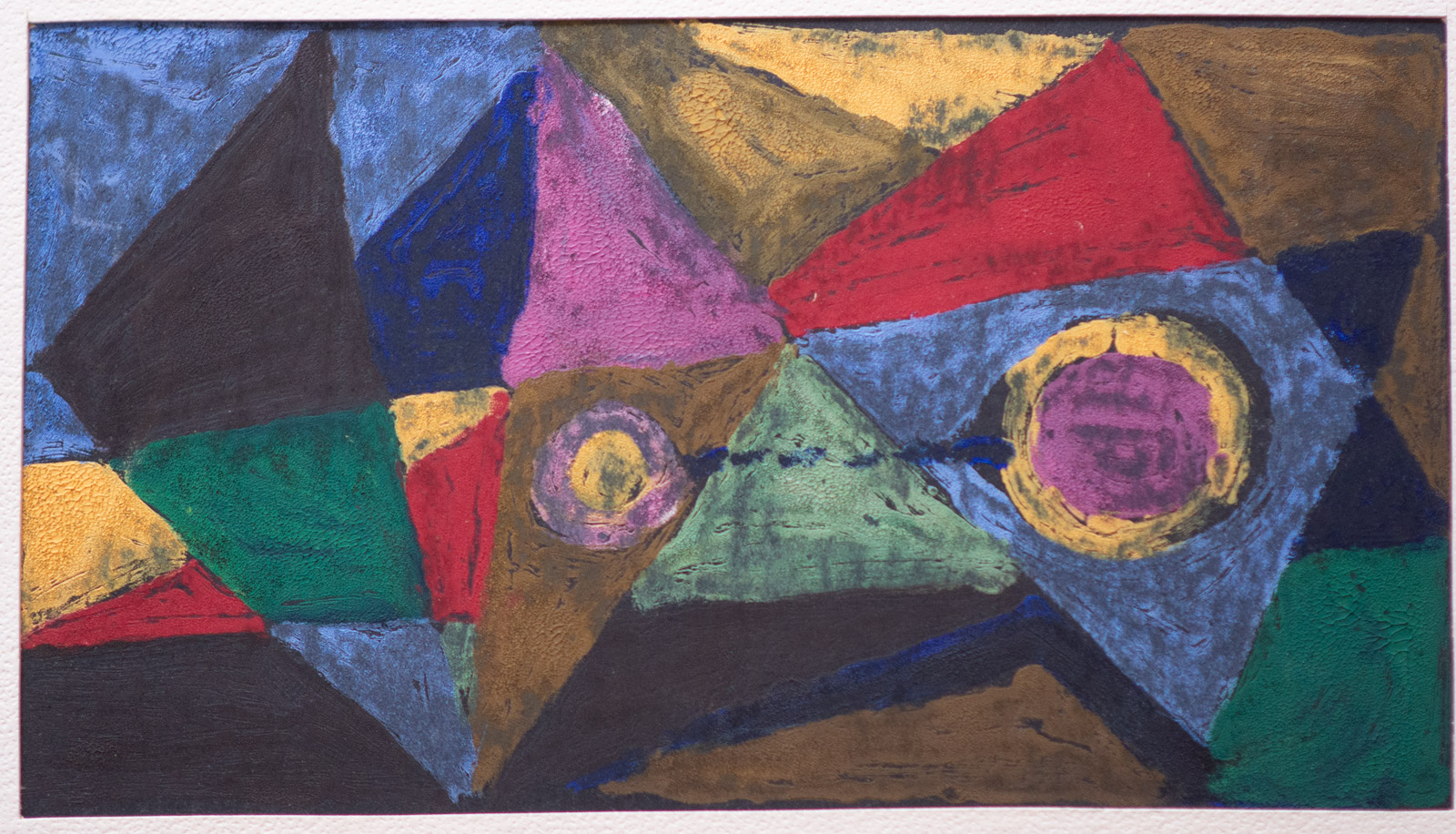

Sing Lim is clean shaven, wearing glasses and a printer’s apron. A cigarette dangles from his mouth. In the background, a printing press rolls, making a clacking sound. Lim moves his paintbrush quickly across a smooth plate of glass. Using purple, green, red, and yellow paints, he creates an image of a woman. He places a sheet of paper over the plate, presses down, and peels back the paper to reveal a monotype print.

This was a common occurrence in Lim’s shop and one that was captured on film in 1963 for the NFB documentary In Search of Innocence. Lim’s eldest daughter, Shirley Joe, who resides in Vancouver, recalls visiting her father’s print shop on East Hastings Street after school with her two younger sisters. She remembers the rows of presses, all different sizes. Her father had put aside his art to focus on his printing business by then, and in 1978 he retired altogether, “just when mechanized printing was coming in,” she says. After he retired, she remembers him retreating to their basement and working quietly on his illustrated children’s memoir, West Coast Chinese Boy.

“He kept to himself,” Joe says. “He didn’t share his past with us.” It wasn’t until Lim’s memoir came out the following year that the family learned more about his earlier life. Since Lim’s death in 1993, the bulk of his prints, oils, and drawings have come into the family’s possession. Lim’s portfolio and life in Vancouver’s Chinatown community offer a rare glimpse of an artist who defied social expectations and faced down racism to pursue his passion for art.

Lim was born in 1915 and raised in Canton Alley, in the city’s self-segregated Chinatown, the youngest of four brothers and a sister. The family lived on the top floor of a five-storey tenement. There were two other tenements in the alley, gated at Pender Street following the 1907 anti-Asian riot. The Lim apartment had a small parlour, two bedrooms, a kitchen, and a washroom. The family used “every inch of space,” Lim wrote in his memoir, “even the fire escapes outside to hang fish and dry greens.”

Lim’s father, Low, immigrated to Canada at 18, a year before the Chinese head tax was implemented in 1885. “My father was one of the first Chinese in Canada to cut his pigtail or queue,” Lim wrote in his memoir. “That meant he could never return to his native land.” In 1900 he brought Shee Chow from Hong Kong to be his wife. Lim’s father worked as a cobbler, and his mother took in sewing from local tailor shops.

Lim credits his art—and sense of humour—for carrying him through the pervasive and systemic racism he confronted growing up. He first realized the “fun of art,” he wrote in his memoir, when he was six years old and made paints from shoe dye and the pulp of berries. Using cast-off brushes, he created images on wrapping paper.

On weekday evenings, Lim attended Chinese school. He liked using the calligraphy brush to draw pictures. “I loved drawing and decided that one day I would be an artist,” Lim documents in his memoir. He also writes about receiving encouragement from his third-grade teacher, Miss Scott at Central School a couple of blocks away.

Lim was 14 when his mother died. She had been attentive toward him, as were his older sister Nellie and his Uncle Jing. He dedicated his book to all three. Lim’s older brothers took up manual work, and Lim was expected to follow in their footsteps when he enrolled in Vancouver Technical School in 1933, an all-boys school on the city’s east side. But he found a way to learn a trade—and pursue art.

Known as “Slim” by his classmates, Lim especially enjoyed the printing course run by Lewis Elliott, a dedicated instructor. Students produced the Van Tech yearbooks in Mr. Elliott’s print shop classroom, hand-setting the type and using plates for illustrations. When the presses were rolling, they sounded “like a car backing up,” one student wrote in a yearbook.

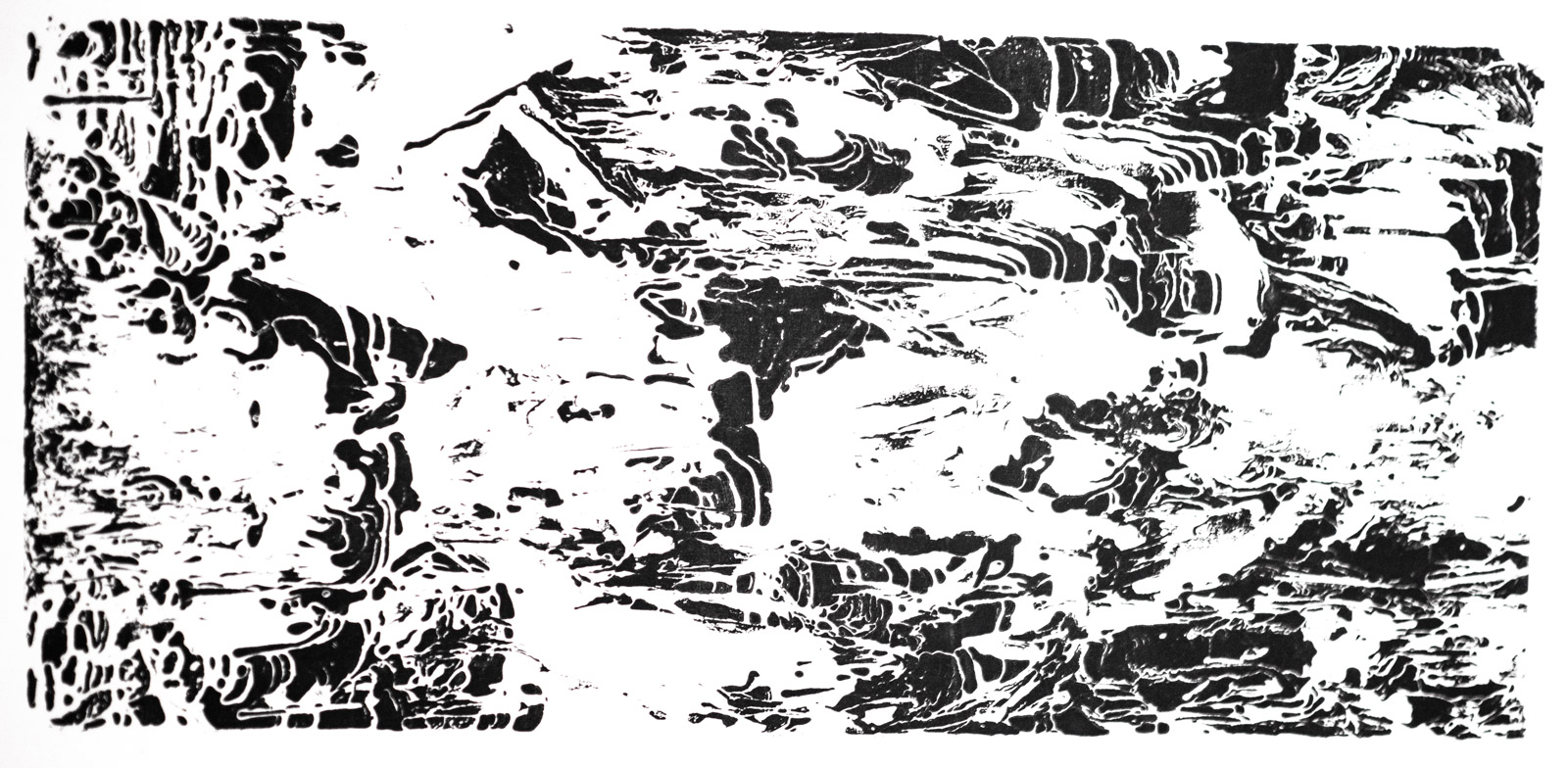

Lim joined the popular Linocut Club sponsored by Mr. Elliott. Students carved on a linoleum block, then inked it with a brayer. The block was covered with paper that was then pressed and peeled back to reveal the image. Students could make multiple prints from the same plate. Lim contributed linocuts to the yearbooks through his graduation in 1935 and until completing night classes in 1939.

“The Chinese printer, in his everyday work, uses over 2,000 characters, with which he must be quite familiar,” Lim wrote in an illustrated article for the 1936 yearbook. Lim went on to describe the Ho Sun Hing print shop, established in Chinatown in 1910, a place he frequently visited. The Chinese Times newspaper would roll off the shop’s presses from 1914 to 1992.

Lim entered the Vancouver School of Art, now the Emily Carr University of Art and Design, in 1941. The postsecondary school did not have a culturally diverse student population, unlike the east-side public schools Lim had attended. During the next four years, he continued working part-time and received two scholarships. In a juried exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery in 1943, Lim exhibited a lithograph titled Young Girl. At graduation, he was praised by the art school director, especially for his graphic illustrations.

Lim continued to meet creative people when he moved to Ottawa and worked as a poster artist in the graphics department of the National Film Board from 1945 to 1947. Among his new friends was Henri Masson, who had toiled as an engraver for 22 years before becoming a professional artist.

“He was a genuine friend who let me use his studio, “ Lim wrote in the afterword of his memoir, “took me on sketching trips and introduced me to the difficult technique of doing monotypes, a medium I still like.”

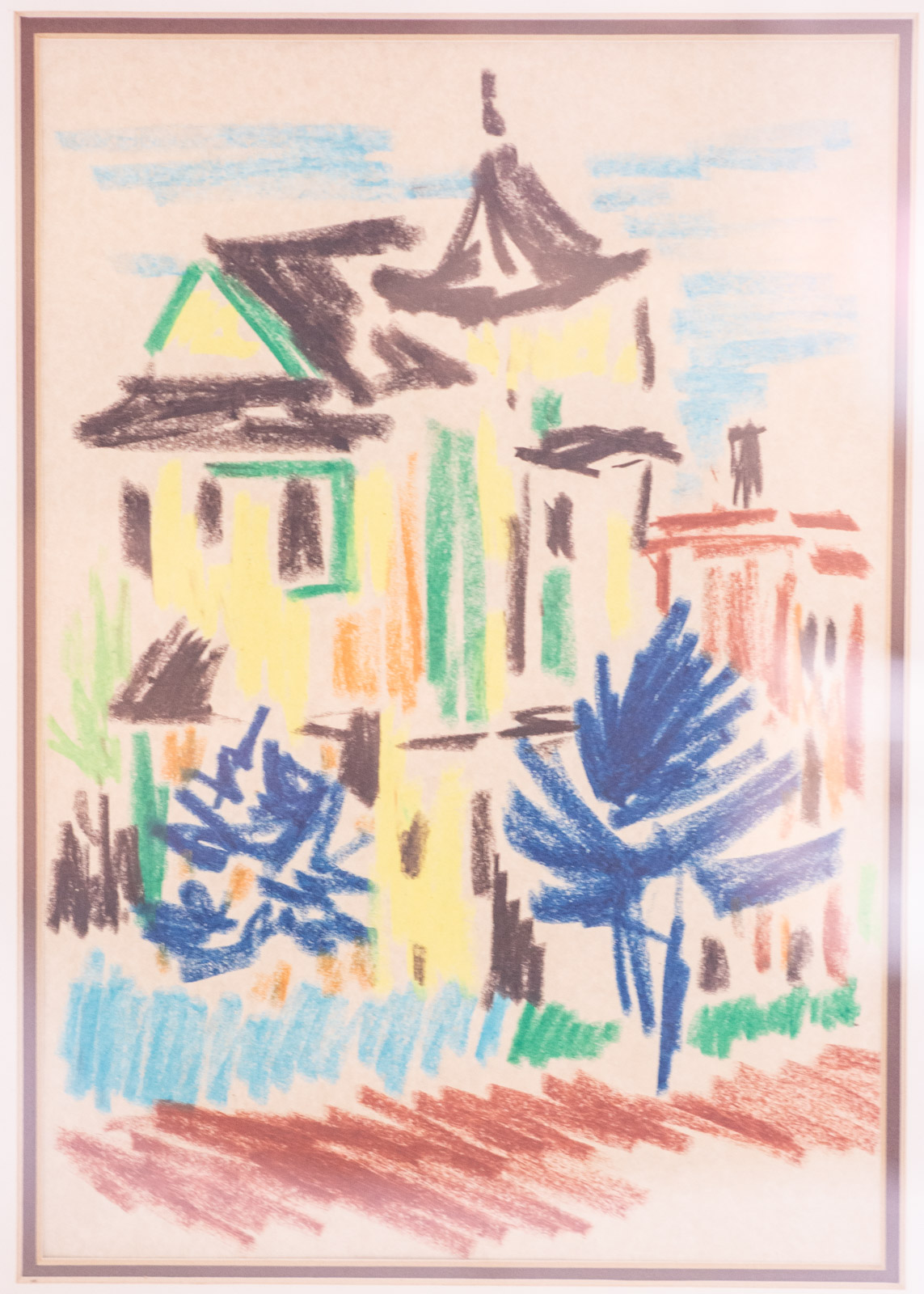

Donald Buchanan, an NFB colleague, put Lim in touch with gallery owner Agnè s Lefort in Montreal. Lim had a solo exhibition of monotypes at her gallery in 1952. Bill Kinnis, another colleague, visited Lim when he returned to Vancouver, and the pair went to a Chinese opera. Lim always enjoyed sketching the performers.

The postwar years were prosperous for Chinatown. In 1947, Chinese Canadians were granted the vote and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 was repealed. By 1959, Lim had established his own printing business near the Chinatown area. That year, he had a solo exhibition of monotypes at the Laing Galleries in Toronto, reported in the English-language newspaper Chinatown News. A Globe and Mail review praised Lim’s depictions of children at play, calling the images “dramatic, bold, without cuteness but with sympathetic candour.”

In early 1962, a headline in the Chinatown News read, “Artist-printer Sing Lim has finally taken the plunge after all these years,” following Lim’s marriage to Ping Louie. The next year he had an exhibition of monotypes and brush drawings at Vancouver’s Danish Art Gallery, but his work and family commitments began to take priority, and only after retirement in 1978 did he return to his art.

The 22 monotypes illustrating his memoir were exhibited at the Art Emporium on Granville Street in December 1979. “Every print was sold,” his daughter says.

“I found in art a more universal culture,” Lim wrote in his memoir, “and I wish I had done more with it.” It is uncertain if Lim was discouraged in later life or if he simply didn’t have time for his art, but his artistic legacy is undoubtedly all the more remarkable for the challenges he faced.

When Lim died at 78 in 1993, his nephew Timothy Lim gave a moving eulogy, as noted in Chinatown News. He spoke of his uncle’s last days at Mount Saint Joseph Hospital, making posters and drawing pictures for the patients “because he enjoyed making other people happy.”

And in 2016, Joe says, her family received a collection of her father’s artwork from Frances Long, the daughter of Jack and Joy Long, artists and long-time friends. “Her father kept some of our father’s art for us,” Joe says. “He thought we might be interested in having the art when we got older.” A framed monotype of the “bear paw feast” is displayed on the wall of her family home.

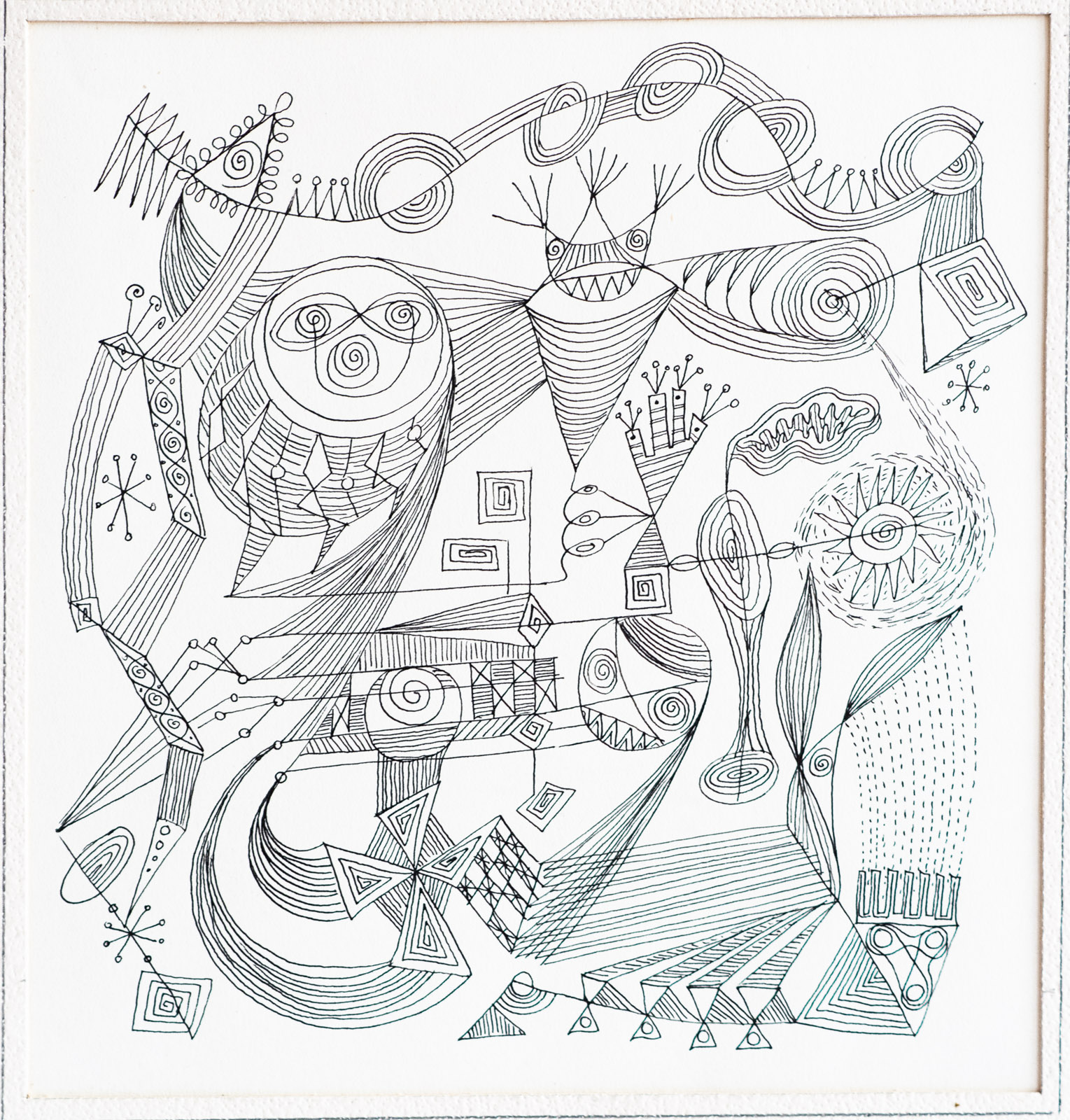

“I marvel at the colours,” Joe says of her father’s art, “and the lines which range from simple single lines to complex detailed lines. I hope that his grandkids will be able to help preserve all his work and see West Coast Chinese Boy reprinted for a new generation to enjoy.”

All artwork for this story was photographed from the family collection, courtesy of Shirley Joe. Read more community stories.