This story is the 13th in our series on the hidden history of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. Read more.

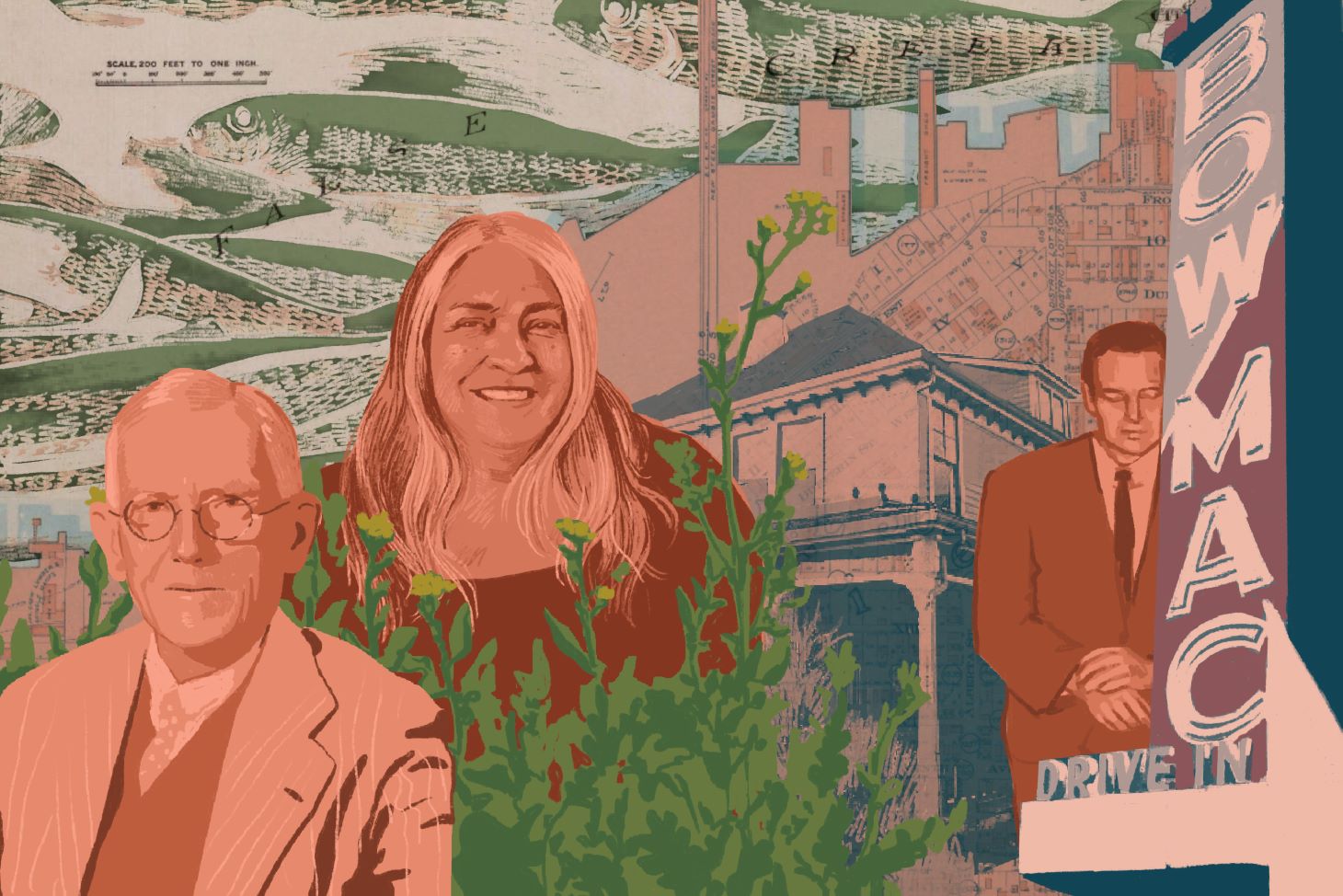

The most notorious resident of Vancouver’s Fairview neighbourhood spent only nine days there. For over a week in June 1965, the radio announcer Rene Castellani lived in a station wagon atop the Bow-Mac car dealership sign on West Broadway and Alder. As a stunt for the Jimmy Pattison-owned business, Castellani pledged not to come down from the seven-storey sign—the largest freestanding sign in North America—until every car in the lot was sold.

Meanwhile, as detailed by crime writer Eve Lazarus, Castellani’s wife, Esther, was in the hospital after being slowly poisoned by her husband, who wanted to marry the radio station’s 25-year-old secretary. Her recovery would end when Castellani came down from his perch. Convicted of murder, he spent 12 years in prison.

Although a Toys “R” Us location has replaced the car dealership—the Bow-Mac sign is obscured but still visible—Fairview remains a bustling area that centres around West Broadway, the area most commonly known as Fairview Slopes. The neighbourhood includes, at the bottom of those slopes, Granville Island and False Creek South. Given its density and easy access via the Burrard, Granville, and Cambie Street bridges, Fairview is often viewed as an extension of downtown Vancouver. Some might see it as a more straight-laced version of the West End. It’s ironic then that Fairview—bounded north and south by False Creek and West 16th Avenue and east and west by Cambie and Burrard Streets—started as the city’s original suburb and has worked its way to the centre while cycling through every possible identity, including industrial area, diasporic hot spot, and tourist playground.

As with most Vancouver neighbourhoods, Fairview’s story begins in the forest—in this case, a dense wall of fir trees. The beaches around where the Burrard Street Bridge presently stands were described by Stó:lō Nation writer Lee Maracle as “a common garden shared by all the friendly tribes in the area” where fish, oysters, berries, and wild cabbage were among the foods harvested. After European settlement, the Canadian Pacific Railway, which owned the land in the area, began building its shipyards in False Creek in 1887. (Later, in 1916, Granville Island, first known as Industrial Island, was built in 1916 from material dredged from False Creek.) The neighbourhood was christened by CPR Land Commissioner L.A. Hamilton, who was also responsible for the tree names of its cross streets.

In 1891, with the introduction of a streetcar line that connected to Mount Pleasant and downtown Vancouver (via the first Granville Bridge), Fairview emerged as an affordable residential area. In Becoming Vancouver, historian Daniel Francis quotes a 1907 Province article describing Fairview as “one of the better-class suburbs of the Terminal City.” A few homes from the Fairview’s first decades survive, including Fairview House, built in 1892 by Dr. John Reid, who served as Queen Victoria’s honorary physician, and Hodson Manor, from 1894. According to Michael Kluckner’s Vancouver Remembered, Japanese and Sikh communities formed near West Fourth Avenue and Granville, close to their lumber mills on False Creek. Later, as the city’s Jewish community migrated from Strathcona, the original Jewish Community Centre was built on Oak Street and West 11th Avenue in 1928.

The first decades of Fairview’s history also saw the introduction of now-iconic institutions. In 1906, Vancouver General Hospital on West 10th Avenue—the area above the Slopes occasionally described as the Heights—replaced the 50-bed City Hospital on Beatty Street. On that same site, the University of British Columbia first held classes in 1915. The campus consisted of one borrowed hospital building and temporary, haphazardly built wooden structures that inspired UBC’s first nickname: “The Fairview Shacks.” In 1922, 1,200 frustrated UBC students embarked on the “Great Trek,” marching from Fairview to downtown Vancouver to embarrass the province into completing its Point Grey campus, which finally opened in 1925.

Long-forgotten now is Fairview’s place in local baseball history, hosting the Vancouver Beavers of the Northwestern at Athletic Park on Fifth and Hemlock from 1913 to 1922. In 1931, Athletic Park hosted the first baseball game under lights before welcoming Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Connie Mack for an exhibition game three years later. In 1939, it was renamed Sick’s Capilano Stadium when it was home to the Vancouver Capilanos, whose owners, the Sick Family, also ran the brewery on Burrard Street until it was purchased by the Molson family. Within a decade, the baseball park was demolished to make way for the Hemlock Street on-ramp of the Granville Street Bridge (in its third and current form). The grass from its field was transplanted when Capilano Stadium moved to Riley Park, where it’s now known as Nat Bailey Stadium.

From the 1920s onwards, Fairview was zoned to allow for low-rise apartment buildings as businesses formed around West Broadway as well as Cambie and Granville Streets. In the South Granville area, one can still walk by the Dick Building (recognizable for its Gothic arches and brick cladding, but no, um, phallic stuff), built in 1929, or watch a musical at the Stanley, which opened as a movie theatre in 1930. Industrial zoning also allowed Purdy’s Chocolates to operate on Spruce Street from 1949 to 1982; unused factory land was repurposed into an adventure playground still known today as Choklit Park.

As industry left the neighbourhood, the 1970s saw the next phase of a decline and redevelopment in Fairview Slopes. Kluckner describes it as “a dying, almost spooky place, by 1970” that was taken over by “students, drifters, and hippies.” One former student, celebrated writer Andreas Schroeder, recalled living in “one of those huge, four-storey, rabbit-warren houses” with a dozen fellow UBC creative writing students in the early ’70s. One night there was a fire, and his housemates scrambled outside: “10 writers could be seen standing on the lawn below, surrounded by boxes and piles of manuscripts, while their partners, abandoned or ignored, were just crawling out of the smoke.” In the ensuing decades, many of the rooming houses and family homes have been replaced by townhouse complexes.

At the bottom of the hill, in 1968, South False Creek was purchased by the city from the province (which had obtained it from the CPR). The community-minded developments, which included housing co-ops and leasehold properties, accentuated public and park spaces. Granville Island, with chain-and-forge and rope companies that served resource-extraction industries no longer thriving, fell into an existential quandary. This dilemma was solved through a bold plan conceived by Liberal MP Ron Basford, head of the Canadian Housing and Mortgage Corporation, to convert the factories and warehouses into a mixed-use space that allowed for pedestrian and vehicle traffic, and for industrial, educational, and retail. Since the Granville Island Public Market opened in 1978, it’s been beloved by tourists and locals alike. Basford, who was also responsible for Canada’s adoption of the metric system, passed away in 2005 and is commemorated with a park in his name on Granville Island’s southeast corner.

Despite occasional interventions from groups like the Fairview Residents Association and Community Action Society (FRACAS—best acronym ever), development in Fairview has continued steadily since, with SkyTrain links running through Cambie and Broadway. Demography shows that Fairview has a higher-than-average number of seniors and childless people, and the lowest rate of unemployment. With the Broadway Plan intent on turbocharging population density—already second-highest in the city behind the West End—Fairview will continue to offer a resting spot to those who need it.

Read more Vancouver Neighbourhood stories.