In his new book Incredible Crossings: The History and Art of the Bridges, Tunnels and Ferries That Connect British Columbia, historian Derek Hayes traverses the province in hundreds of striking photographs, unearthed anecdotes, and historical details. This excerpt, which describes three Vancouver bridges that have since disappeared, is published with the permission of Harbour Publishing.

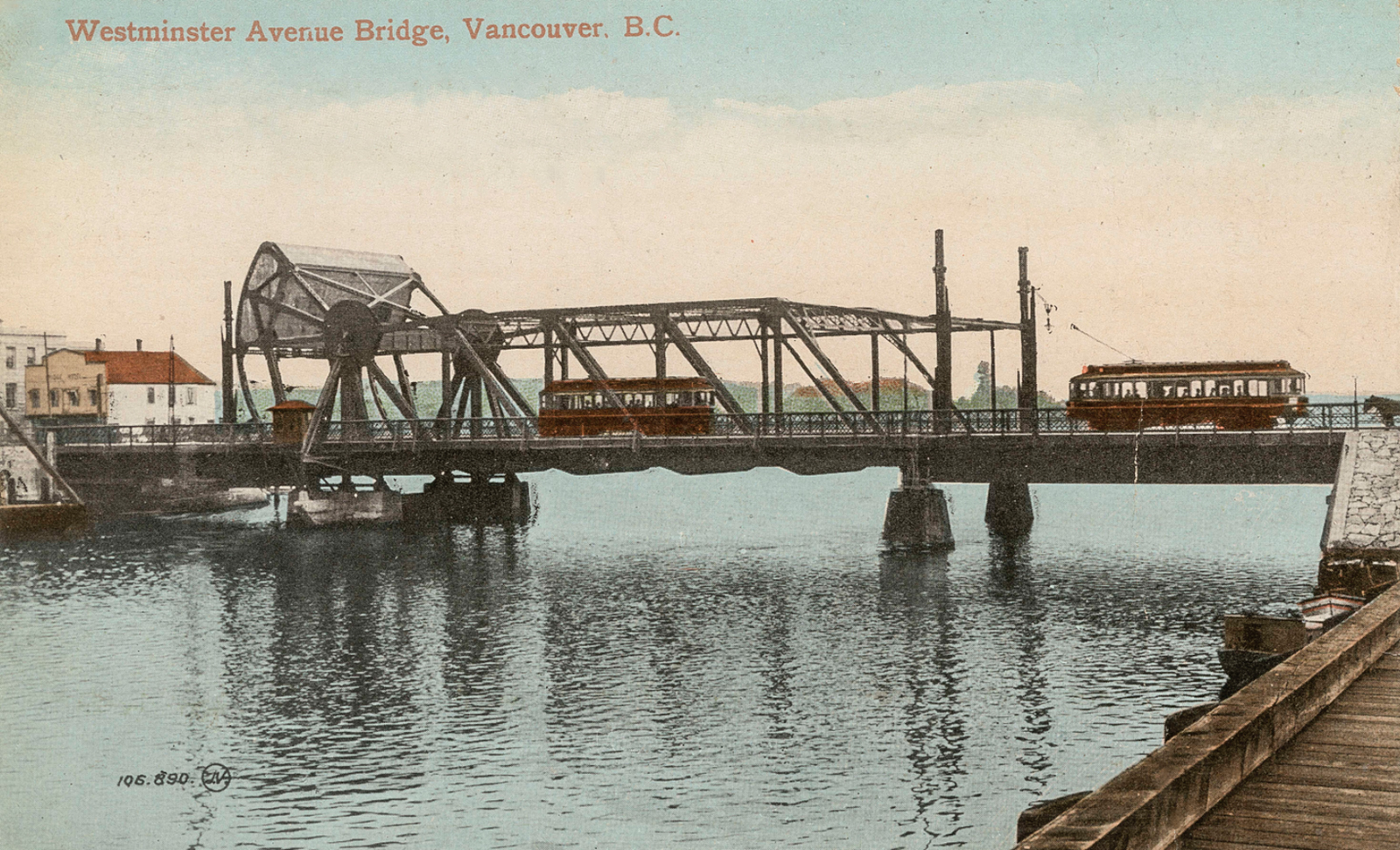

Westminster Avenue / Main Street Bridge

The Main Street Bascule Bridge with last BCER cars to cross.

The Westminster Avenue Bridge, after 1910 the Main Street Bridge when the road name was changed, was the first bridge across False Creek, having been built about 1872 at the narrowest part of the inlet to carry a road to New Westminster. It was a simple wooden plank-and-pile trestle. This worked because the water here was very shallow, with the area east of the bridge drying to mud flats at low tide. In 1890, what was effectively another bridge was attached to the west side to carry Vancouver’s first streetcar tracks over False Creek to Mount Pleasant.

More use of the eastern part of False Creek led to some dredging and, about 1905, the construction of a new steel bascule bridge to allow access for larger vessels. This new bridge lifted the entire road to near vertical. This bridge did not last very long, however, for plans were afoot to fill in the eastern creek to provide railway terminals and facilities, first for a partial fill by the Great Northern, approved by Vancouver voters in 1910, and then for filling the rest by the Canadian Northern Pacific in 1913. The bridge was progressively encroached on by fill and was demolished in 1921.

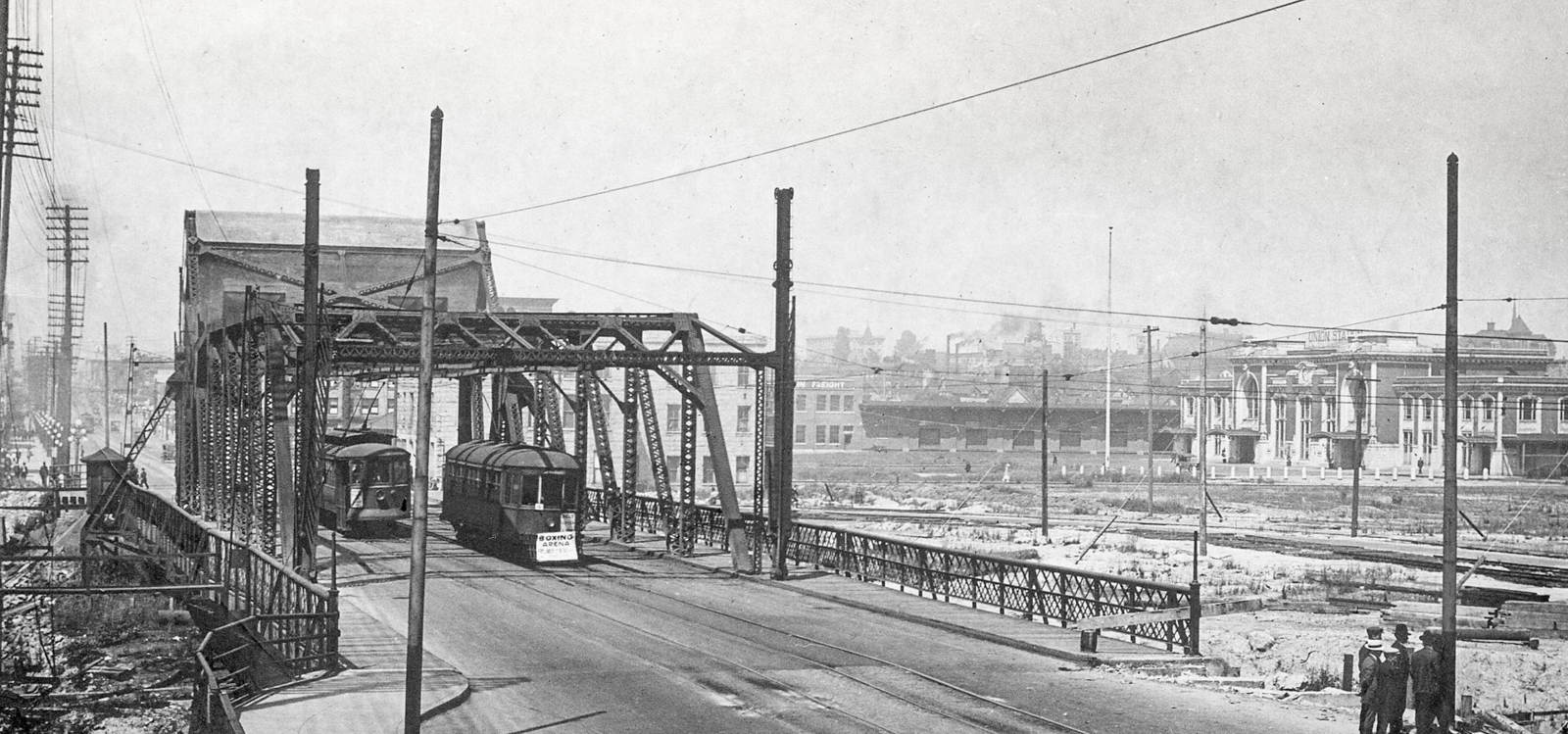

Great Northern Bridge

The Great Northern Bridge and tracks over False Creek.

Another False Creek bridge that is no longer in existence was the Great Northern Railway trestle bridge, built by the railway’s subsidiary, the Vancouver, Westminster & Yukon Railway (VW&Y), in 1905.

At the turn of the 20th century the Great Northern Railway had a problem: it needed access to Vancouver, but the land was all tied up by its bitter rival, the Canadian Pacific, which had been given much land as grants in 1885. By 1910 it had solved this problem by filling in part of eastern False Creek, but before that it obtained access via a line from New Westminster through swampy land north of Burnaby Lake and the line of the Grandview Cut (the cut was made later, in 1913, to improve the difficult grade). This was track built by the VW&Y.

An initial temporary station was at today’s Main Street and First Avenue, but this was too far away from Downtown, and the railway built the trestle bridge with a swing span to access the north shore of False Creek, where a station and limited yards could be built. Today the station site is the Sun Yat-Sen Chinese Garden.

The Canadian Northern had the same access issue as the GNR until it also solved the problem by filling in more of False Creek. Its initial tri-weekly transcontinental service, begun in late 1915 after the transcontinental line was completed, ran into Vancouver using Great Northern lines, crossing on the False Creek bridge to the station on Pender Street. So the Great Northern False Creek bridge was for a brief period one of great significance, carrying trains both from the United States and Eastern Canada into Vancouver.

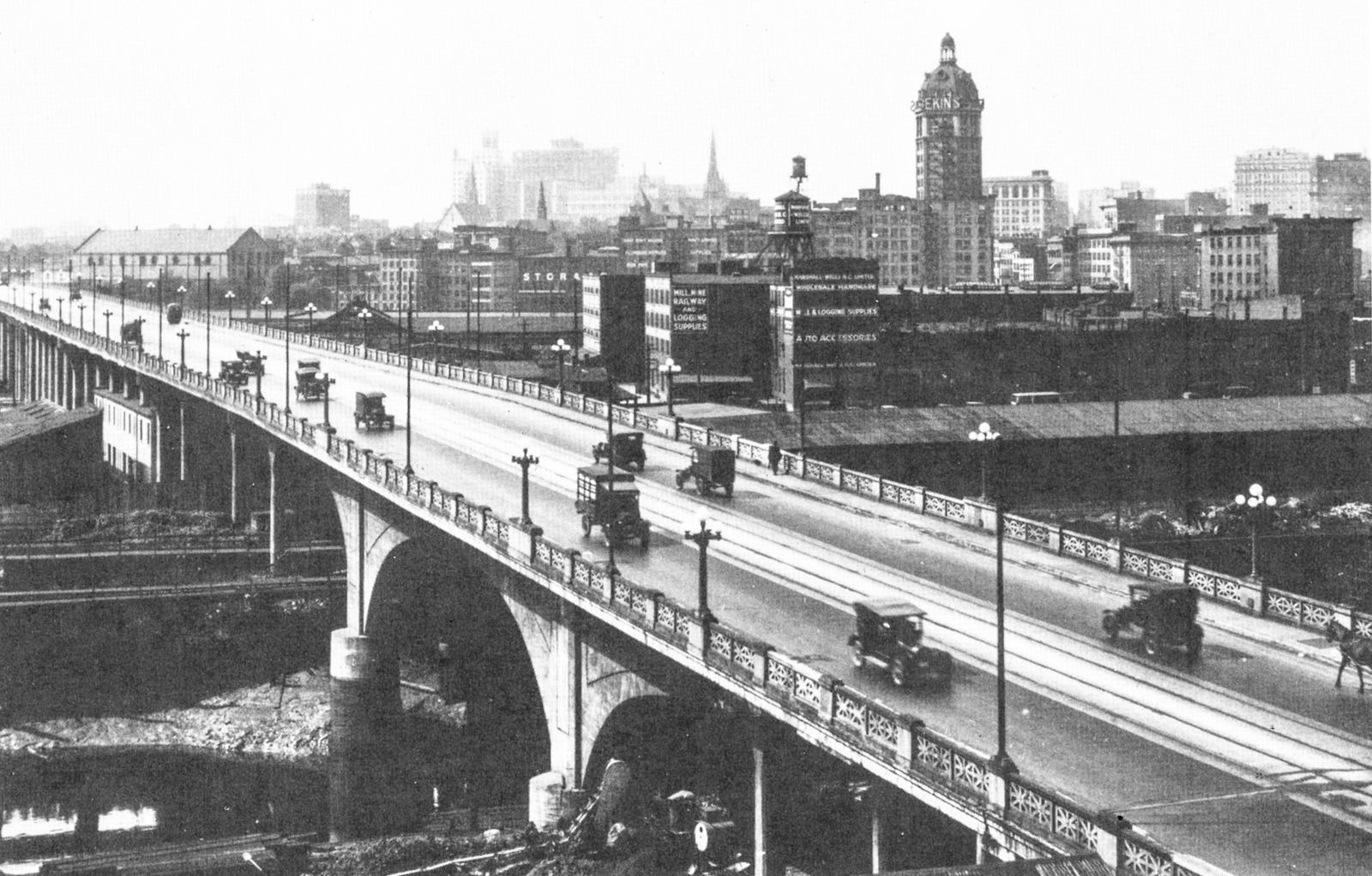

Georgia Viaduct

The Georgia Street Viaduct, including unused streetcar tracks.

The first Georgia Viaduct was the city’s answer to Downtown access across the marshy flats surrounding False Creek. Opening in 1915, it was at first named the Hart McHarg Bridge after Lieutenant Colonel William Hart-McHarg, killed that year in World War I action, but it was commonly called the Georgia Harris Viaduct, because it connected those two streets. However, Harris Street was renamed East Georgia Street after the viaduct’s completion, so simply Georgia Viaduct made more sense.

The design was initially considered to be an engineering marvel because it included a 25-metre-long reinforced concrete span over an arm of False Creek and some of the GN tracks, thought at the time to be the longest in North America. (The other part of the bridge was a steel-truss design.) It was also hailed as “incombustible,” which, in an age where many bridges were made of wood, seems to have been a big deal. Unfortunately, it turned out that too much sand had been included in the mix, and the bridge almost immediately suffered from structural safety concerns. Every other street light was removed to reduce weight, and streetcar tracks laid across the viaduct were never used.

The viaduct was demolished in 1972 and replaced by a more robust concrete structure that had been intended as a part of the Downtown freeway system, advanced by the Vancouver Transportation Study of 1968. Despite freeways being thoroughly rejected in 1972 by Vancouver voters, the new Georgia Viaduct had somehow survived, perhaps because work on it had already begun by 1967, including the leveling of 15 blocks in the Chinatown area, including Hogan’s Alley, a Black neighbourhood. The twin, one-way viaducts opened on 9 January 1972 amid protesters who tried to prevent Mayor Tom Campbell’s limousine from driving across the structure.

The southernmost viaduct leads east from Georgia Street, while the other is for westbound traffic and leads onto Dunsmuir Street; for this reason it is often referred to as the Dunsmuir Viaduct. It seems, however, that the anti-freeway activists will finally win the day, 50 or so years later, for in 2015 Vancouver City Council voted to tear down the twin viaducts and replace them with groundlevel roads, having discovered from traffic surveys that only about 10 percent of the traffic entering or leaving Downtown actually uses the viaducts, probably because the east ends merge onto normal city streets.

Read more local history stories.