These days, the property at 525 Sixth Street in New Westminster barely warrants a second look. But for more than 50 years, the site—now a mixed-use commercial block featuring strip-mall staples like Subway and Save-On Foods—was home to one of British Columbia’s most famous (and notorious) private hospitals.

It was a place that attracted high-profile clientele like Andy Williams and Cary Grant—a sprawling white mansion that, by the late 1950s through the ‘60s, had become known nationwide for its pioneering work in the controversial field of psychedelic therapy.

“When I started looking into it, I had no idea that it would lead to anything,” explains local author and historian Lani Russwurm, who wrote about the facility, called Hollywood Hospital, in an article for his website Past Tense. “But then I realized, ‘Wow, Vancouver has some serious psychedelic history—and not only that, but a pre-hippie psychedelic history.’”

The estate itself was previously the residence of one Charles Major (a stagecoach operator whose route ran between Barkerville and Ashcroft), and was first opened as a hospital in 1919 by Dr. E.A. Campbell. Named for the holly bushes on the property, the 55-bed facility is thought to have been home to the first formally-planted garden in mainland B.C. Prior to 1956, it was best-known as a place for alcoholics to kick the habit, and was recognized for its innovative (if unusual) treatment approaches, including doing away with straitjackets and introducing an open-door policy for patients.

Family photograph showing the future Hollywood Hospital in the background, 1915. Photograph courtesy of the New Westminster Archives.

In a 1980 issue of Vancouver Magazine, former Province journalist Ben Metcalfe (who spent considerable time writing about the hospital in its heyday) described it as “an enormous, rambling, white-painted cedar and stone mansion that stood much obscured by the great holly trees for which it was named.”

And as unorthodox as Hollywood Hospital’s methods might have been in the beginning, things took an even sharper turn with the arrival of two men: Dr. J. Ross MacLean and Al Hubbard. MacLean purchased the facility in 1956, following the death of founder Campbell; and between 1957 and Hollywood’s closure in 1975, MacLean and Hubbard supervised more than 6,000 acid trips—not just for alcoholism, but for anxiety disorders, depression, and marital discord—with a success rate of 50 to 80 per cent.

“Hubbard’s whole thing was disseminating LSD to influential people,” Russwurm explains, seated at Matchstick Coffee in Vancouver’s Chinatown. “That’s what he was best known for: just going around, spreading LSD all over North America. To him, it was like spreading the gospel. And he was quite the zealot about its benefits.”

Labelling Hubbard a zealot is hardly an overstatement. Known colloquially as the Johnny Appleseed of LSD, he had such a pervasive influence on the drug subculture of the 1950s and ‘60s that, during a Beverly Hills party for the early acid generation’s gurus (later recounted by journalist Metcalfe), psychologist Timothy Leary turned to him and said “Al, I owe everything to you.”

Described by Metcalfe as “squat, slightly rumpled, wryly jocular, and extremely confident gnostic,” Hubbard had led a fascinating life prior to his arrival at Hollywood Hospital, including stints as a rum-runner for George Reifel and a period working for the OSS (the precursor to the modern CIA).

He had also helped ship uranium for the Manhattan Project, spent time in prison, and claimed to have personally “turned on” author Aldous Huxley. Having taken his first acid trip in 1951, Hubbard was among the earliest North Americans to do so, and thereafter, had crisscrossed the continent attempting to sell the medical establishment on its potential.

In 1953, he convinced Dr. Abram Hoffer, head of the Canadian government’s psychiatric research facility in Saskatoon, to begin exploring the possibilities of LSD. He also helped Dr. Donald Ewen Cameron of McGill University set up a similar program in Montreal (which, thanks to the CIA, had much more sinister results). And in 1957, a year after MacLean’s purchase of the Hollywood Hospital, Hubbard arrived on his doorstep.

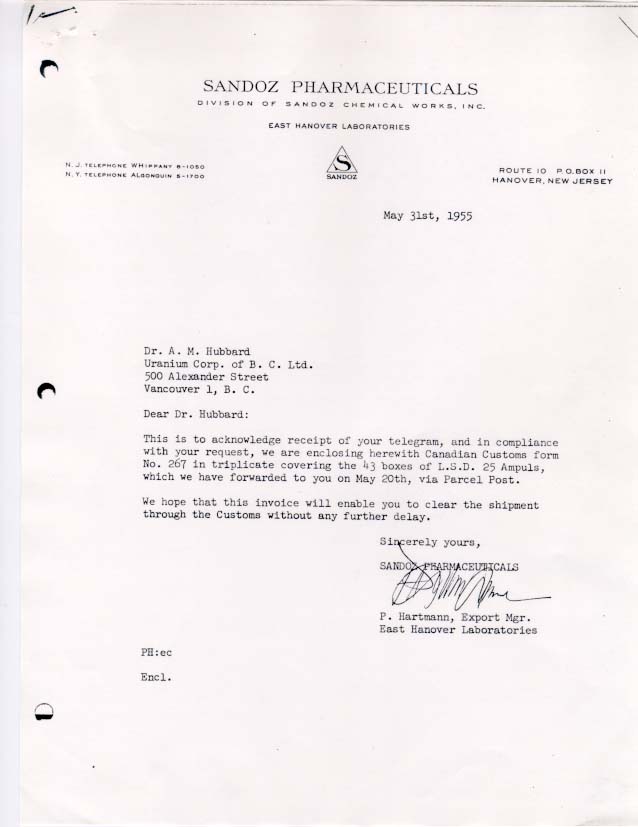

In the late 1950s, psychedelic therapy came without virtually any of the social stigma it carries today. For starters, it was legal; Hubbard—the only licensed importer in Canada—obtained his acid (known then by its more formal name LSD-25) directly from Sandoz, the Swiss company that had first manufactured it back in the 1940s. The drug had also yet to become associated with the counterculture elements that would later lead uneasy governments to declare it illegal.

A letter between Al Hubbard and Sandoz Pharmaceuticals, 1955. Photograph courtesy of the New Westminster Archives.

In fact, as Russwurm points out, it was developed during part of the same wave of innovation that led to the creation of the first psychiatric medications. “There were two very distinct periods when it came to LSD: the ‘50s and the ‘60s,” he says. “And during the ‘50s, there was a bunch of serious research going on with pharmaceuticals in general—that was when the first pharmaceuticals came along that had any positive psychiatric effect at all. Drugs like antipsychotics and antidepressants. And LSD was part of all that.”

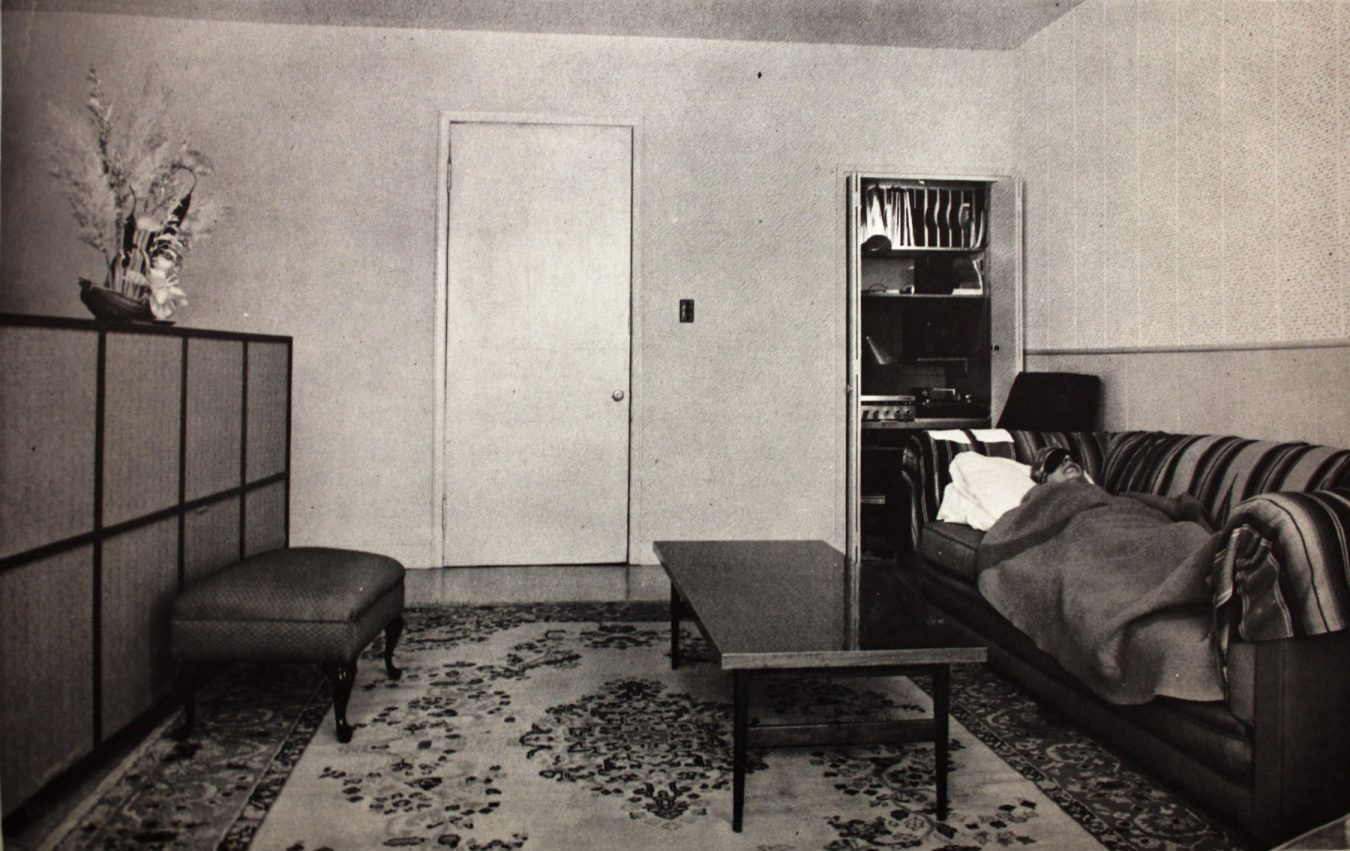

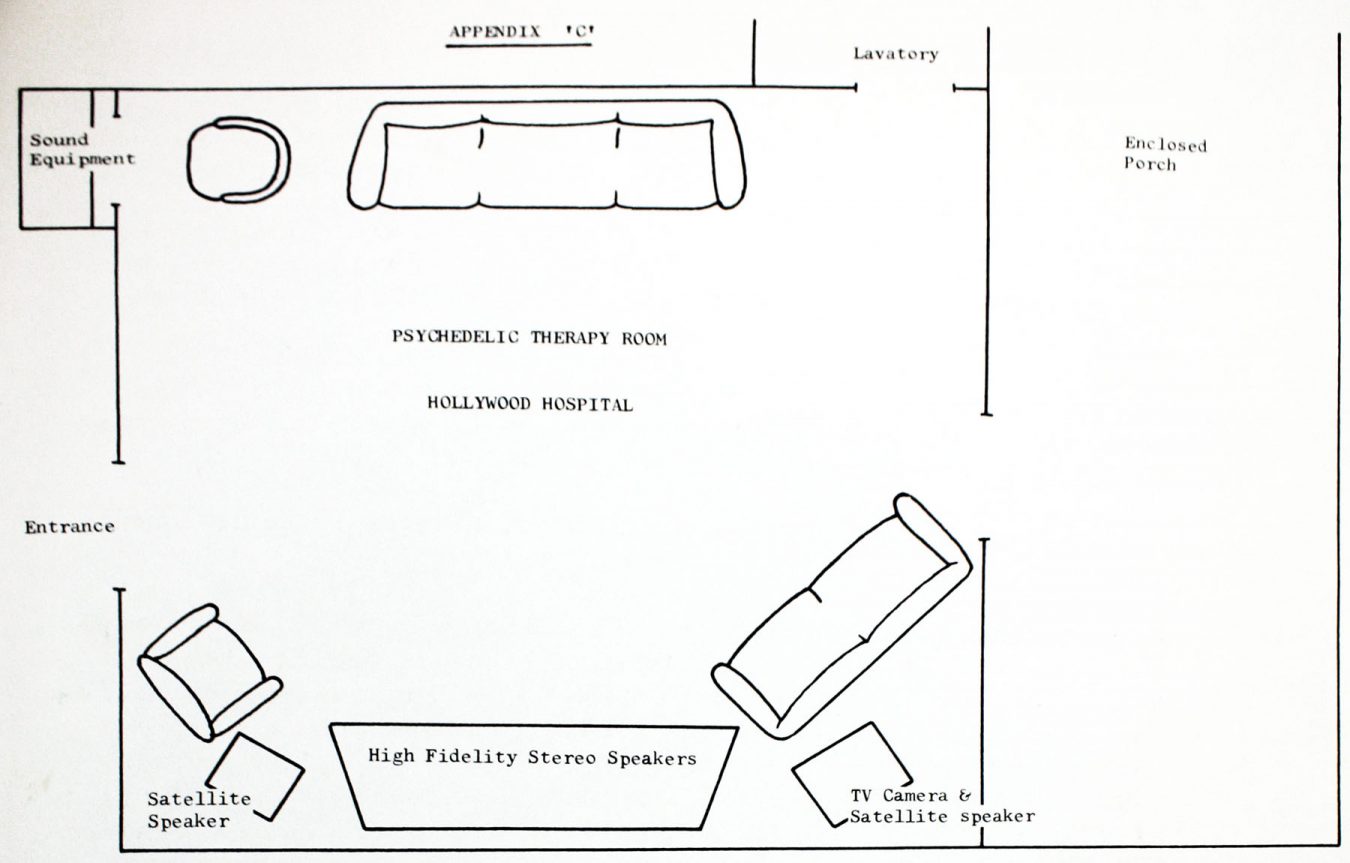

Hollywood Hospital charged its patients on a sliding scale; usually between $600 and $1,000 for psychedelic treatment (although some received it pro bono). Sessions took place in a specialized Psychedelic Therapy Room, which featured Hi-Fi speakers, plants, and several visually stimulating paintings, including Salvador Dalí’s Last Supper and Crucifixion, and Paul Gaugin’s Buddha.

The sessions were as clinical as possible under the circumstances, each one being presided over by Hollywood Hospital staff including MacLean, Hubbard, and a nurse. Notes were taken in the room, and employees were on hand both to prepare patients before treatment and to discuss the experience with them in real-time. Each participant in what was dubbed “The Experience” was asked to draw up an autobiography, including details of childhood, family, and sexual and religious experiences, as well as reasons for wanting to take part in the process.

As MacLean wrote in a 1965 report entitled LSD-25 And Mescaline As Therapeutic Adjuvants: Experience From A Seven-Year Study, this exercise “undoubtedly orientates the patient to self evaluation, and otherwise sets the stage for much of what will be experienced. This facet of preparation is also viewed as an integral part of the total therapy.”

By mid-1959, MacLean and Hubbard were rich men. MacLean had used his largesse to purchase Vancouver’s iconic Casa Mia on Marine Drive, and Hubbard drove a two-tone Rolls-Royce, owned a fleet of airplanes, and had a lab on one of the Gulf Islands. In Hubbard’s case, it’s unclear exactly where his money came from; Russwurm contends that it was through work as both the scientific director of the Uranium Corporation of BC and head of a company called Marine Manufacturing, while other historians have suggested that he never fully retired from clandestine government work.

But while he may have been wealthy, there’s one thing Hubbard was not: a doctor. His credentials had in fact been purchased from Taylor University, a degree mill that was little more than a Chicago post office box. When confronted by Metcalfe on the subject, his response was characteristically glib: “Hell, Ben—I never had a pair of shoes ‘till I was 12 years old and left Kentucky! When would I find time to become what you call a real doctor?”

Despite its financial and medical success, the therapy conducted at Hollywood Hospital wasn’t viewed favourably by the medical establishment. Vocal opponents included Vancouver General Hospital psychiatry head Dr. James Tyhurst, and the BC Physicians College, which threatened to withdraw the hospital’s subsidies if it couldn’t demonstrate the program’s effectiveness.

Hollywood Hospital Psychedelic Therapy Room floor plan. Photograph from “LSD-25 And Mescaline As Therapeutic Adjuvants” by J. Ross MacLean, 1963, courtesy of the New Westminster Archives.

It was this demand that led to the hospital’s most high-profile moment when, in the fall of 1959, journalist Metcalfe wrote a six-part, front-page series on psychedelic therapy for the Province. The pieces were an attempt to improve the hospital’s image, exploring the drug’s history and efficacy, and climaxing with a firsthand account of the LSD experience. “The first men to return to Earth from outer space will have much less difficulty convincing you of what they saw than those few people who have had ‘The Experience’ with the drug LSD-25,” Metcalfe wrote in the Sept. 2, 1959 edition of the Province. “But within hours after taking the drug myself I had been there and back several times and to many other places besides.”

The series was a sensation. Even today, Metcalfe’s analysis of the drug, and the patients it affected, is remarkably levelheaded, having been written in a world before the scaremongering of the 1960s had taken hold (“toxically, it is less harmful to the body than an aspirin compound,” he notes at one point). And even the therapeutic process—recorded by nurses and transcribed later by Metcalfe—was surprisingly progressive for 1959; after looking at his own hands and remarking “what wonderful things the hands are,” Metcalfe spent a solid six minutes weeping. “This is all repressed masculinity,” Hubbard had said, consoling him. “This is what we bury to become men.”

While its primary use was in treating alcoholics, LSD-25 was also employed for a less ethical purpose: to try “curing” homosexuality. Although, as MacLean explained in his 1965 report, this ended up having an unexpectedly positive effect: “Few homosexuals in our group have attained a satisfactory heterosexual adjustment, yet many have derived marked benefit in terms of insight, acceptance of role, reduction of guilt and associated psychosexual liabilities.”

It was during this period that Hollywood Hospital attracted its most famous guests, including Williams, Grant, and Vancouver Sun publisher Don Cromie. But for the facility, and for the drug that had become its star attraction, the moment of fame wouldn’t last.

As the 1950s turned into the 1960s and LSD became more and more associated with North American counterculture, the American government moved to ban its use. In 1965, Sandoz stopped making the drug; in 1966, the American government made it an illegal substance, and in 1968, Canada did the same (two vocal champions were Tyhurst and University of British Columbia researcher Pat McGeer, who claimed, baselessly, before the legislature that LSD was “every bit as hellish as heroin”).

By the early 1970s, Hollywood Hospital had fallen on hard times. New Westminster City Council tried, unsuccessfully, to shut it down in the spring of 1970, and around the same time, it ran into trouble with fire inspectors over the condition of its buildings.

Without psychedelic therapy as its flagship, the hospital introduced other things, including multivitamin injections. In December of 1974, the government announced it would no longer continue providing bed subsidies, and in July of 1975, Hollywood Hospital closed its doors. In the July 8 edition of the Province, owner MacLean called the closure “inevitable,” bitterly citing a number of issues, including crumbling facilities and a treatment program suffering from “government indifference, obstruction, and bureaucratic myopia.”

At this point, Hubbard had already gone on his way. By 1980, when Metcalfe tracked him down for a follow-up story in Vancouver Magazine, he was living a markedly different life from his Hollywood Hospital tenure, instead spending his days in an Arizona trailer park and working as a security guard. “By then, he had blown through his fortune,” Russwurm says. “And that was largely because he didn’t believe in commercializing LSD at all. For him it was more of spiritual thing.”

Today, Hollywood Hospital is long gone, but the research it pioneered has been taken up by a new generation of medical professionals, who have been testing its effect on everything from increasing creativity to alleviating depression and anxiety. And, true to Metcalfe’s assessment in 1959, LSD has since been recognized as among the safest recreational substances by the Global Drug Survey (third after magic mushrooms and cannabis). The drug has also gained some degree of mainstream acceptance; micro-dosing is reportedly common in Silicon Valley, and the late Steve Jobs, in a 2005 interview with author John Markoff, claimed it was one of the most important things he had ever done.

Put another way, as Metcalfe wrote back in September of 1959: “Not every experience is the same. Not everyone who has The Experience necessarily benefits dramatically from it. But all are agreed that it is the only really fantastic experience accessible to the ordinary mind in our time.”

From the Archives: This story was originally published on April 10, 2019. Learn more about local history in our Hidden Vancouver series.