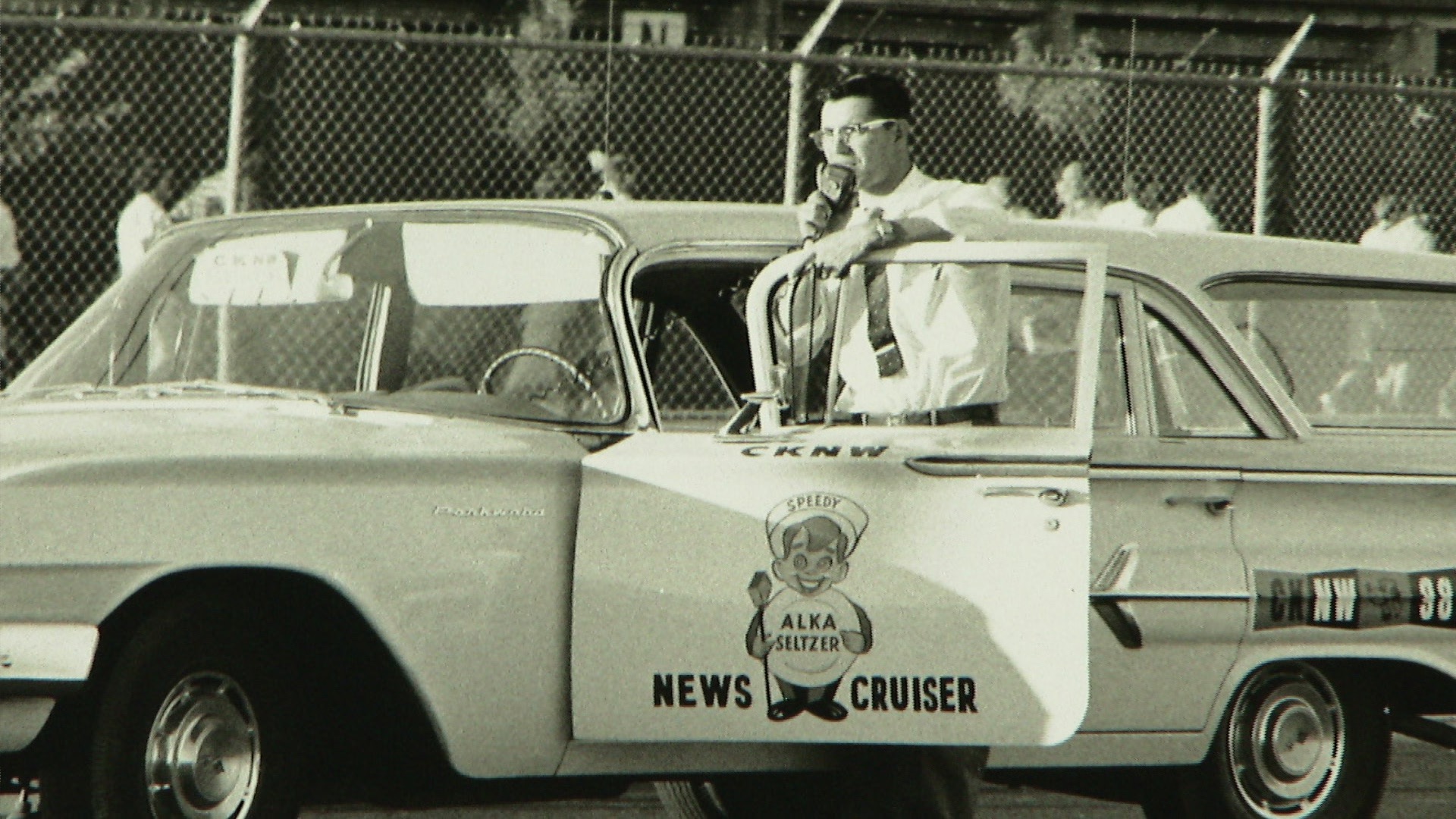

In his four decades as a reporter for CKNW, George Garrett broke countless stories and earned a reputation as an intrepid, trustworthy reporter who wasn’t afraid to go undercover in search of the truth. In this story from our archives, we sat down with Garrett after he finally decided to uncover his own story, in his 2019 autobiography.

“I’ve always been insatiably curious,” writes George Garrett in the opening to his autobiography.

And over the course of his 43-year career as a reporter for CKNW, that curiosity served him in good stead. During those four decades Garrett was on the scene at murder trials and prison riots, protest actions and crime scenes, gaining access to cops and criminals alike.

He covered protest actions, including the 1993 standoff at Clayoquot Sound, which ultimately resulted in 85 per cent of the rainforest being legally protected. He reported on the O.J. Simpson trial and the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles—the latter landing him in the hospital with a broken jaw. During the trial of serial killer Clifford Olson, he was among the first to learn of the controversial “money for bodies” deal. Dubbed the “intrepid reporter” by the late politician and pundit, Rafe Mair, he was known as much for his discretion as for his relentless pursuit of a story. But now, after nearly a half century on the radio, and almost 20 years of retirement, the 84-year-old Garrett realized that he had one more story to tell: his own.

“I started thinking about leaving something for my grandchildren,” he tells me. “When they were teenagers, I thought they might want to know what their Papa had done during his life. I started writing it that way, and then I thought: ‘Gee, there’s a lot of information here that might be of interest to the broader market, too’.”

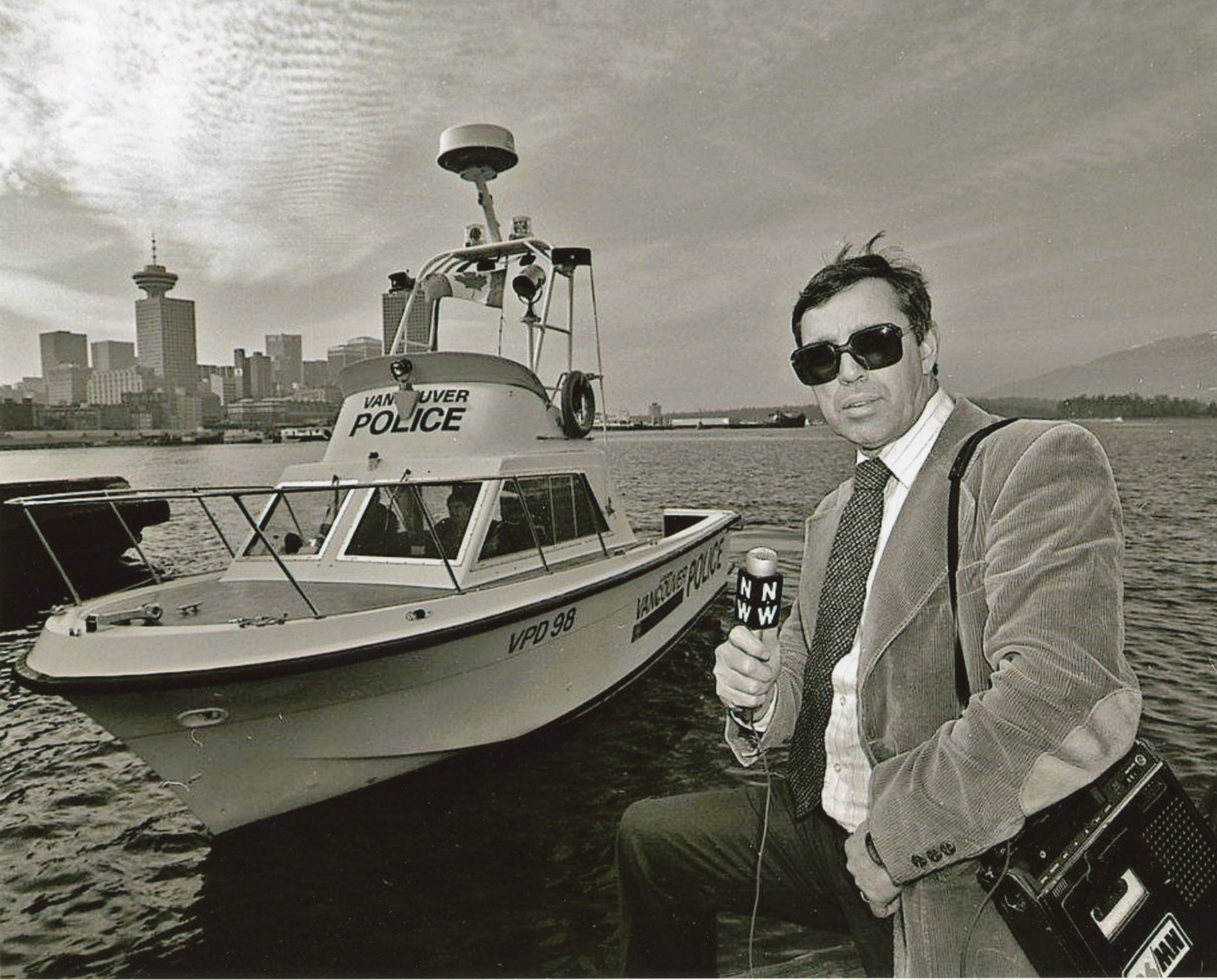

The result is George Garrett: Intrepid Reporter (Harbour Press, 2019). At turns funny, harrowing, and engaging, it’s the story of Garrett’s journey from Moose Jaw farm boy to one of the most respected reporters in the business. It’s also a fascinating behind-the-scenes glimpse of a bygone era—not just for journalism, but for the police departments and courtrooms Garrett regularly covered. It’s a look back at notable moments in B.C. history, and at the impressive list of contacts he managed to cultivate—criminals and judges, beat cops and homicide detectives (after reporters were barred from the VPD’s Major Crimes Unit in the 1990s, Garrett was given his own key).

Clayoquot Sound, 1993. Photo by by Mark van Manen/The Vancouver Sun.

“I got to know the team of traffic accident investigators and the motorcycle cops,” he writes. “I knew detectives and their supervisors in all squads. I knew the names of bootleggers, pimps, prostitutes, gamblers, and burglars. I was given free access to police information for years, because I was trusted.”

His radio debut came in 1952 at just 17 years of age, when he was ostensibly hired off the street by a station in North Battleford, Saskatchewan. Having grown up on a farm during the Depression, he had no formal radio training, and in fact, didn’t even graduate high school (“Up until then, I’d had pretty good marks, but I got interested in girls,” he laughs). Nonetheless, within four years, he had landed a job at CKNW, moving with his new wife Joan to far-off Vancouver. During the early years, he worked the 4pm-midnight shift, which involved regularly calling hospitals and police stations in search of a story and, as a result, he began to build the relationships with police personnel that would come to define his career.

“Cultivating contacts is so incredibly valuable,” he notes. “And gaining the trust of the police community was the most important thing. It wasn’t just the VPD: once the word spread that you were a trusted reporter, it went all the way through the police community, the RCMP, and the municipal departments. And word was, you could trust George. But it could also go the other way. I know some reporters who abused their trust, and the word would get out that way, too.”

Police boat, 1980s. Photo courtesy of Alex Waterhouse Hayward.

Garrett sat in courtrooms, and befriended judges, some of whom would later provide information impossible to get by any other means. A number of sensational stories, including the impaired-driving arrest of a Supreme Court justice, came about from ride-alongs with police. He documented the city’s sex-trade, both on the street, and in more upscale venues such as The Penthouse. Through a source at the Main Hotel, he uncovered a handful of crooked cops dealing in stolen goods.

And, as his career progressed, Garrett was given carte blanche to cover whatever he wanted—a privilege not extended to many other reporters—and he began working undercover to expose corruption and criminal activity. He took a job as a tow-truck driver to uncover fraud at a local towing company. He infiltrated a secret meeting of the Bill Bennett Social Credit government at Government House in Victoria. He covered the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, during which he was assaulted and ended up in the hospital. He posed as an accident victim to reveal a personal injury lawyer’s illegal practices (as evidence of his commitment to a story, Garrett’s claim, for a soft-tissue back injury, required a digital rectal examination).

“I was fascinated with the job from day one,” he says. “I loved doing it. And a story was a story. We were always careful about accuracy, of course, but the thrill was in beating the other guy. I loved doing that, and I think every reporter wants to have an exclusive. With CKNW, our policy was: if you have a story, put it on the air. Make sure it’s right, but get it out there. You didn’t have to vet it with anybody, unless it was something sensitive.”

Owing to the nature of his work, many of those stories would prove to be sensitive indeed. During the manhunt for, and trial of, serial murderer Clifford Olson, Garrett led the pack on radio coverage. Not only was he the first to hear of Olson’s controversial “money for bodies” deal with the government (in which the Crown paid Olson’s wife for the location of his victims) but he was one of the first reporters to publicly acknowledge that B.C. had a serial killer at all.

King Island with Gary Hanney. Photo credit by Hanney Collection.

“I was among the first people to say that there was a serial killer at large,” he recalls. “I talked with my boss, Warren Barker about it. We had to make a judgement call. And we realized that it would shock the community, but that this person was still at large, so people needed to know, so they could keep an eye on their children.”

Outside of his work, Garrett’s book also explores the ups and downs of his personal life—his marriage to Joan McIntyre in 1956 (they met, suitably, at a radio station when she and some friends came in to request a record,) Joan’s later battle with Alzheimer’s disease, and the tragic loss of their son Ken, in a canoeing accident at the age of 24. Today, Garrett’s curiosity remains undiminished. For the past three years, he has been developing and fundraising for a volunteer society for cancer patients, picking them up and driving them to treatment. And while he’s no longer chasing down exclusives, he continues to watch the development of the city’s media landscape, and the stories it produces, with fascination.

“I think it’s much more difficult now for reporters,” he muses. “There’s so much pressure on them to be flexible. For instance, a radio reporter now has to take a camera. They do a shot for online media, and have to sometimes do video, and take a still camera, and think about how it’s going to look, as well as what it’s going to sound like on the air. They have to be even more talented.”

He laughs.

“That said, when I hear stories from Victoria these days—entitlement expenditures for questionable purposes, for example—and everything coming out of Ottawa, I wish I was a reporter again.”

This article from our archives was originally published on March 29, 2019, and updated on May 11, 2021. Discover evocative stories from the Community.