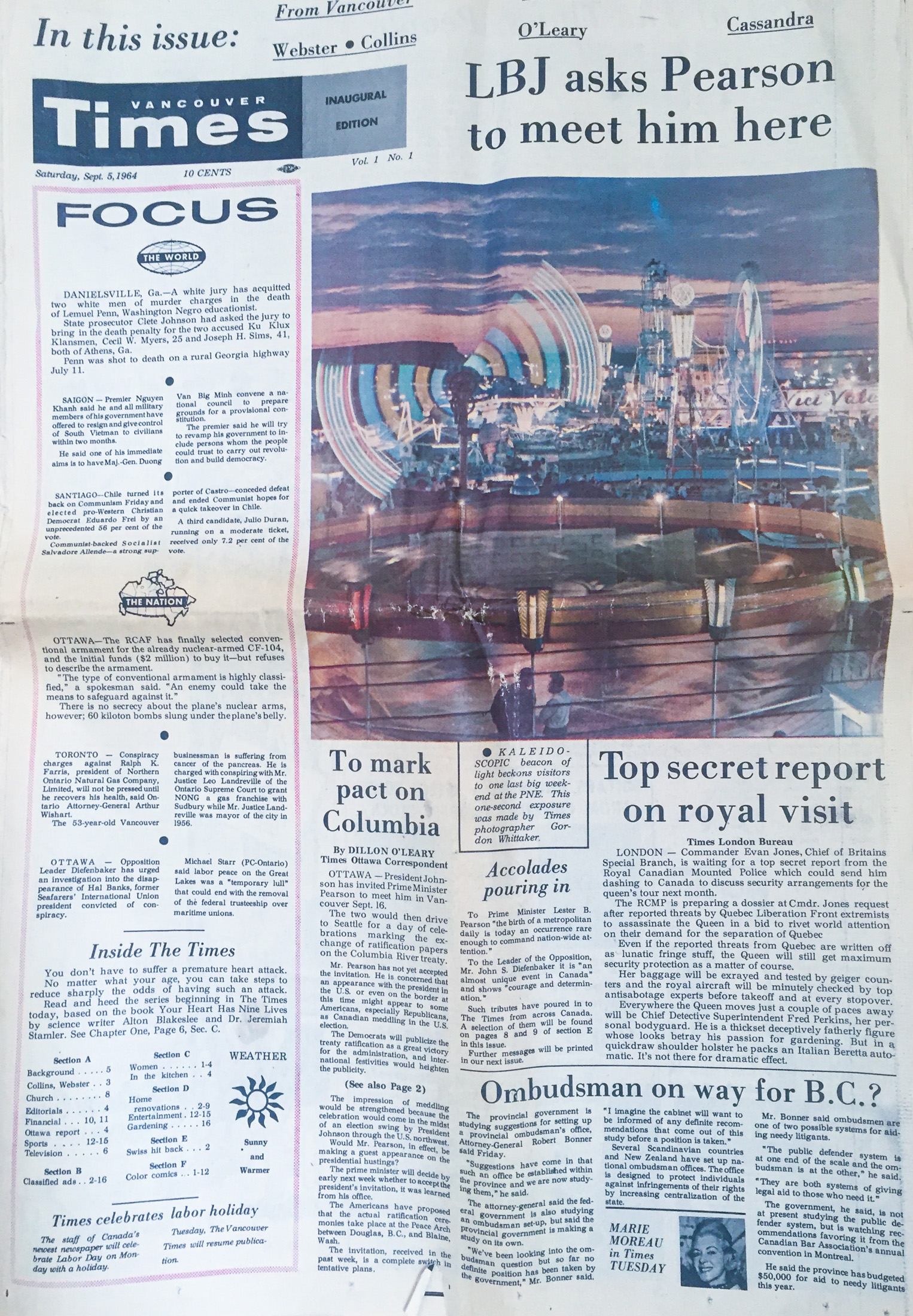

On September 5, 1964, a new daily newspaper appeared on Vancouver doorsteps. The broadsheet boasted a snazzy design, a news scoop about a pending visit by the U.S. president, and, most remarkable of all, a kaleidoscopic, full-colour photograph of the Ferris wheel at the Pacific National Exhibition taken at night with a one-second exposure. It was like a magazine on newsprint. No one had seen anything like it.

After more than four years of planning, raising millions of dollars from ordinary investors, and a steady drumbeat of publicity, the Vancouver Times hit the street. The launch was shaky. The presses were slower than promised, interrupting afternoon deliveries, as trucks were stalled in rush-hour traffic and schoolboy carriers went home for supper. Too few were printed, so copies were unavailable at corner stores. So great was the demand, an industry publication later reported, copies were pilfered from doorsteps, and one hapless carrier had an entire bag stolen when he momentarily left it unattended on a sidewalk.

The newspaper was the brainstorm of William Val Warren, “a hard-driving and humorless adman,” as he was described in a 1963 profile by Maclean’s magazine. Warren had served in the Royal Canadian Air Force during the war and worked as a newsreel cameraman for the National Film Board on his discharge. He was on his way to Hollywood when he stopped in Vancouver to visit relatives. He decided to stay, getting into the advertising business. He bought Time O’Day Advertising Ltd., a telephone service to which a caller dialling MU4-6131 would get the time after listening to a brief advertisement. The service claimed about 500,000 monthly calls.

He also published the Metro Times, an advertising shopper distributed for free. Many of the mom-and-pop shops who were clients complained about the high cost of advertising in the city’s two daily newspapers, the morning Province (circulation about 110,000) and the afternoon Vancouver Sun (250,000).

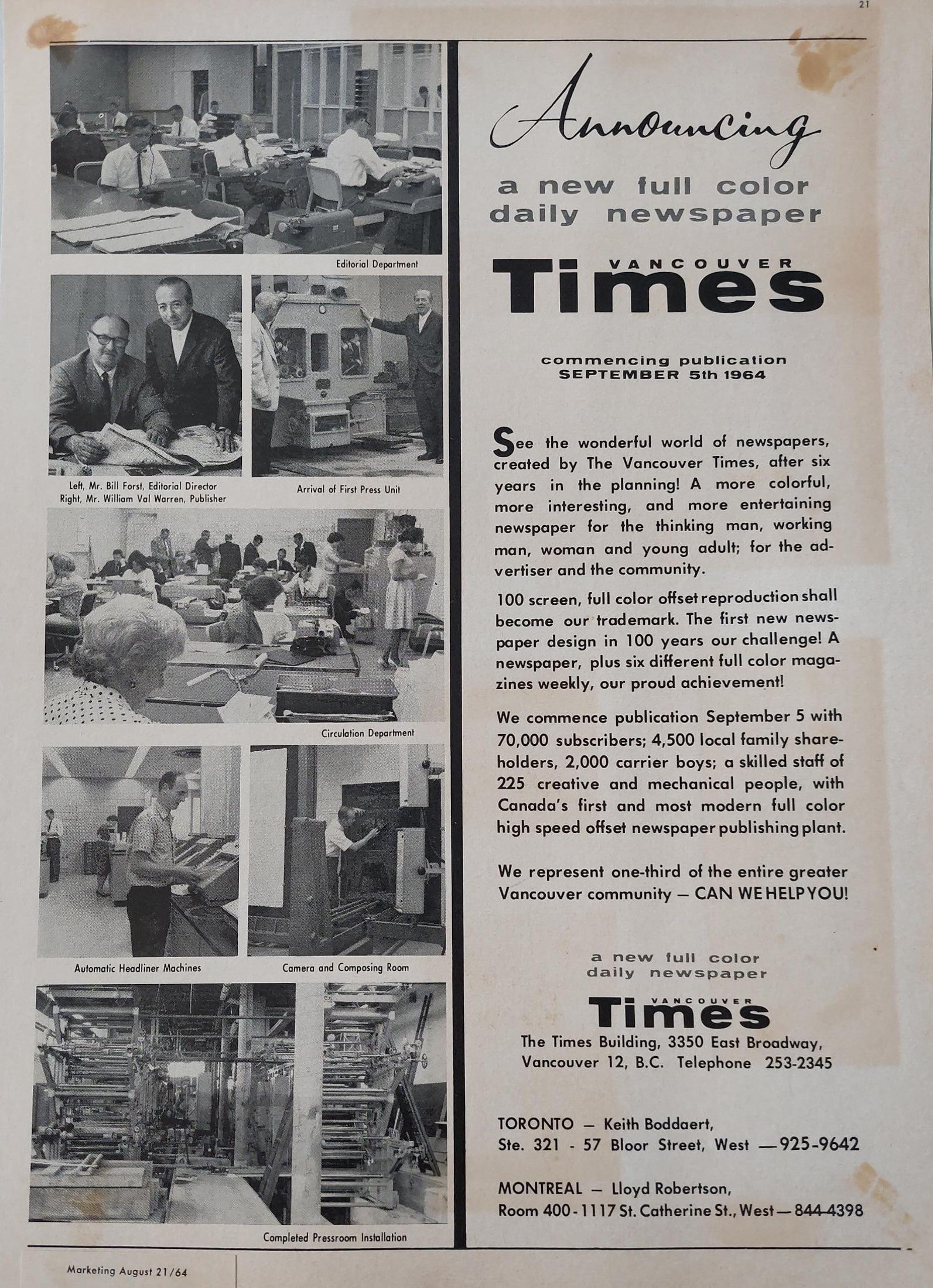

Warren spotted his future at the end of an article in a trade publication. An advance in offset printing technology meant it might be possible to print a daily newspaper with colour photographs. Advertisers could also be enticed to offer their wares in a more distinctive presentation than black and white.

The offset process was cleaner, and it offered crisp images and bold colour reproduction. It also meant a newspaper could be produced without a massive investment in expensive linotype machines and hiring skilled operators. Warren bought the Canadian rights to use the presses and began raising money to launch a newspaper. From the start, he imagined creating a chain of such newspapers across the country.

Announcement of the new full colour daily. Image courtesy of Diane Warren.

The directors of the fledgling Vancouver Times included prominent lawyer Walter S. Owen, a future lieutenant-governor, while the board chairman was Major General Victor Odlum, the former editor-in-chief of the Vancouver Daily World and publisher of the Vancouver Star, who had commanded the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division before becoming a diplomat. A prospectus raised $2 million from small investors excited by the prospect of sharing ownership of a daily newspaper.

Warren took a booth at the PNE and sold 30,000 subscriptions by giving away a slick, 12-page preview edition. “I know we can’t miss,” he told Maclean’s, his optimism verging on cockiness. “I can smell what people want.”

The newspaper bought a former Volkswagen dealership building at 3350 East Broadway just east of Rupert Street, far from the downtown core but closer to the suburbs where Warren anticipated circulation and advertising growth. Two state-of-the-art, six-unit Lithomaster presses were installed.

The inaugural edition. Photo courtesy of the author.

The editorial staff worked under the direction of Bill Forst, who had risen from newsboy to become Province managing editor before quitting to take a gamble on this upstart. The managing editor was Geoffrey Molyneux, an English-born journalist who got his start at the Daily Sketch in London.

It proved harder than expected to lure reporters from the downtown dailies, where union wages and seniority proved a powerful incentive. The Times wound up recruiting flotsam and jetsam from the journalism world, many of them young and willing to take a risk.

Among them was Peter Wilson, a 22-year-old reporter from the Winnipeg Free Press who found himself the number two man on the City Hall beat, though he knew nothing about local issues.

“The big thing we prided ourselves on was having colour,” he says. “Every day on any page. The problem with the offset presses was they turned out to be considerably slower than expected, so our deadlines were hours earlier than the Sun’s. We were always running behind what we could get in the paper.”

An ambitious sportswriter from Victoria finagled a job interview with Forst, as he later recounted in a memoir.

“Have you edited copy?” Forst asked.

“Sure,” Jim Taylor lied.

“Laid out pages?”

“Of course,” he lied some more

“All right, we’ll give you a try.”

The editors and reporters were outnumbered by their downtown rivals and hobbled by early deadlines. Circulation dropped when it was expected to rise. Advertisers failed to materialize, and the Times tried to embarrass a department store by publishing a full page blank except for a few words indicating the space was reserved for Woodward’s. The stunt failed to win over Woodward’s while annoying other advertisers who wondered why the Times was offering free space to a rival.

Wilson remembers potential investors touring the building. He pitied those “honest, hard-working people putting their money in” when he suspected they would never see a dime back. At the same time, he knew his next paycheque depended on their kicking in.

Payments were delayed. When paycheques were issued, the staff stampeded out the door.

“Warren was everywhere, putting on a brave face and predicting expansion to other Canadian cities,” Taylor wrote in his 2008 memoir Hello, Sweetheart? Gimmie Rewrite! “Meanwhile staffers learned to grab their cheques and rush to the bank across the street because if you got there later there might not be enough left in the account to cover yours.”

One day, half the newsroom staff was fired. “The reason they were letting us go,” Wilson recalls, “was because we had no dependents. They should have let go those with dependents, so they could find jobs.” Those who were fired got a head start on finding new work.

Nothing seemed to staunch the bleeding. The Times trumpeted the hiring of radio hotline host Pat Burns as a columnist. His acidic approach did not translate well to print, and he, too, soon quit. Eleven months after the launch, the Times announced it was suspending publication.

WE’RE TAKING A PAUSE, read the banner headline on the front page.

The newspaper promised to return after finding financing, but it had already blown through about $5 million. Jack Webster, who had been a columnist for the newspaper, conducted a post-mortem published by the Sun, calling the demise “a pathetic end of a bold experiment.”

Warren had been pushed out before the final day of publication. He resurfaced a decade later in Palos Verdes, California, where he was promoting his latest invention—a water heater he called the Insta-Hot beverage bar for brewing instant coffee inside cars, boats, and small airplanes.

He later returned to Vancouver where he invented an ultraviolet water purification system, held financial seminars, and raised venture capital. He reached a nadir when he was charged with fraud in a failed restaurant franchise business. A judge in New Westminster dismissed the charge in 1978.

“He was an entrepreneur,” says his daughter, Diane Warren. “My mom said life with him was a financial roller-coaster. He was full of ideas. Sometimes they’d do well, and sometimes they’d flop.”

Though all but forgotten today, the Vancouver Times was a blueprint of the daily newspaper of the future: printed by offset, in full colour, with tabloid supplements, a single union representing all the crafts, produced in a building not downtown but closer to the growing suburbs.

At the time, the afternoon field seemed more profitable, though the long, slow decline of afternoon newspapers had already begun. (In New York in the mid-1960s, the Journal-American merged with the Herald Tribune and New York World-Telegram and Sun to publish as the World Journal Tribune, which lasted eight months before folding.) Television was killing the afternoon daily. In retrospect, a morning Vancouver Times would have placed it in competition with the weaker Province while also providing an overnight buffer for missed deadlines and slow presses.

The biggest losers in the venture were the 5,000 shareholders, whose nest eggs disappeared in a sea of red ink. Most of the journalists found employment elsewhere in the industry. Wilson worked for the Canadian Press wire service before being hired by the Sun, where he was a long-time arts and technology writer.

“For us, it was a ride,” he recalls. “It was fun.”

In his memoir, Jim Taylor remembered Warren as “equal parts entrepreneur, hustler and wheeler-dealer.” The sportswriter returned to Victoria after the paper folded, only to be lured back to the big city by the Sun, where he became one of the best-known—and funniest—sportswriters of his generation.

Taylor kept a framed front page of the final edition of the Vancouver Times on his office wall at his home on Shawnigan Lake on Vancouver Island. He also kept his copy of the inaugural edition, which the family passed on to me after his death two years ago.

Another keepsake from his time with the Times was a letter from the chartered accounts handling the bankruptcy, assuring him that if any assets remained after debts were retired, he would receive $55.87 owing. He never collected.

Read more local history stories.