This story is the fifth in our series on the hidden history of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. Read more here.

The morning of July 18, 1910, a group of Italian workers hired to lay sidewalk on Venables Street for a private contractor refused to continue until they were paid the $2.70 daily rate given to city workers doing similar labour (about $70 in today’s dollars). These unhappy workers proceeded downtown where they persuaded other Italian labourers to join their strike. As the demonstration stretched into a second day, Grandview-Woodland author, historian, and activist Jak King notes, the “reporting… was decidedly dramatic, featuring ‘gangs’ of Italians systematically intimidating workers on city sites.”

This was back in the days when Italians were considered a racial minority, and newspaper coverage reflected their not-yet-elevated status. “The great difficulty with which the police have to contend is the fact that they do all their talking to their fellow countrymen when inducing them to quit work in their native language,” reads an article from the Vancouver Daily News that King quotes. “If their threats could be understood by a white man they could be promptly arrested.” The job action proceeded peacefully for four days until police intervened and arrested two participants, scaring the remaining strikers back to work.

It’s apt that the first participants in Vancouver’s Italian Labourers’ Strike were helping to build a sidewalk in Grandview-Woodland, not only because the area is, along with Strathcona, the historic home of the city’s Italian community, but also because its business artery, Commercial Drive, is one of the city’s liveliest and busiest thoroughfares, intersecting with Broadway and East First, the east-west avenues that connect the city to the suburbs. Maybe it’s because of this combination of energy and location that newcomers to Grandview often end up sticking around. As Charlies Demers writes in his essay collection Vancouver Special, “No group has really left the Drive after settling there, no matter how incongruous the next wave of settlers.”

Up until it was logged at the end of the 19th century, the hilly area, populated by elk and bear, was described as Khupkhahpay’ay, the Squamish word for “cedar tree.” Soon after the region became part of Vancouver, two skid roads that would later become Commercial Drive and Victoria Drive were used to haul felled trees north to Burrard Inlet and the mills in Cedar Cove, where the Columbia Brewery and slaughterhouse were also located. The name Grandview has been attributed to area landowner Edward Odlum, a geologist and city alderman who is said to have installed the city’s first telephone lines, after overhearing the area’s vistas extolled in 1904.

After a streetcar line linking New Westminster and Vancouver started running in 1891, land speculators bought lots in the hopes of developing a posh new neighbourhood around the stop at what is now Venables Street and Clark Drive. Construction, however, didn’t start to boom until the first decade of the next century. Although the hopes that this area would become Vancouver’s new primary elite district were not realized, some prominent bigwigs’ homes—including Odlum’s 1905 turreted Queen Anne at 1774 Grant Street, and Australian Canadian rancher and PNE founder JJ Miller’s sprawling 1908 Kurrajong mansion at 1098 Salsbury Drive—live on as stratified apartments, giving Grandview-Woodland a more distinguished heritage vibe than the rest of East Vancouver.

The Edwardian architecture found on Commercial Drive (renamed from Park Drive in 1911) was also built at this time, tracing a distinctive skyline for its many independently owned businesses. One establishment that remains is the hardware store off Graveley Street, which began as Magnet Hardware in 1915 but is now a Home Hardware.

But Vancouverites don’t trek across town to Grandview-Woodland to buy a bag of nails. The Drive’s magnetism derives from the waves of immigrants from Italy, Portugal, the Caribbean, and East Asia who arrived after the Second World War. In the area long known as the city’s Little Italy, businesses such as Nick’s Spaghetti House, Fratelli Authentic Italian Baking, and Lombardo’s Pizzeria have popped up over the years. For those who’ve eaten their fill of biscotti, there’s goat curry at Riddim and Spice and banh mi at Paris Bakery. Live music and theatre are found at the Cultch and York Theatre, which hosted bands like DOA and Nirvana before an extensive renovation. It is now the home of the beloved East Van Panto.

Further east, on Nanaimo Street, one can buy porchetta and steaks at Columbus Meat Market and cannellini beans and deli meat at Renzullo’s. The recent obituary of the market’s founder, Carmello Renzullo, who arrived from the old country after the Second World War and launched a family-run business, could serve as a template for the stories of many of the Italian families in Grandview-Woodland.

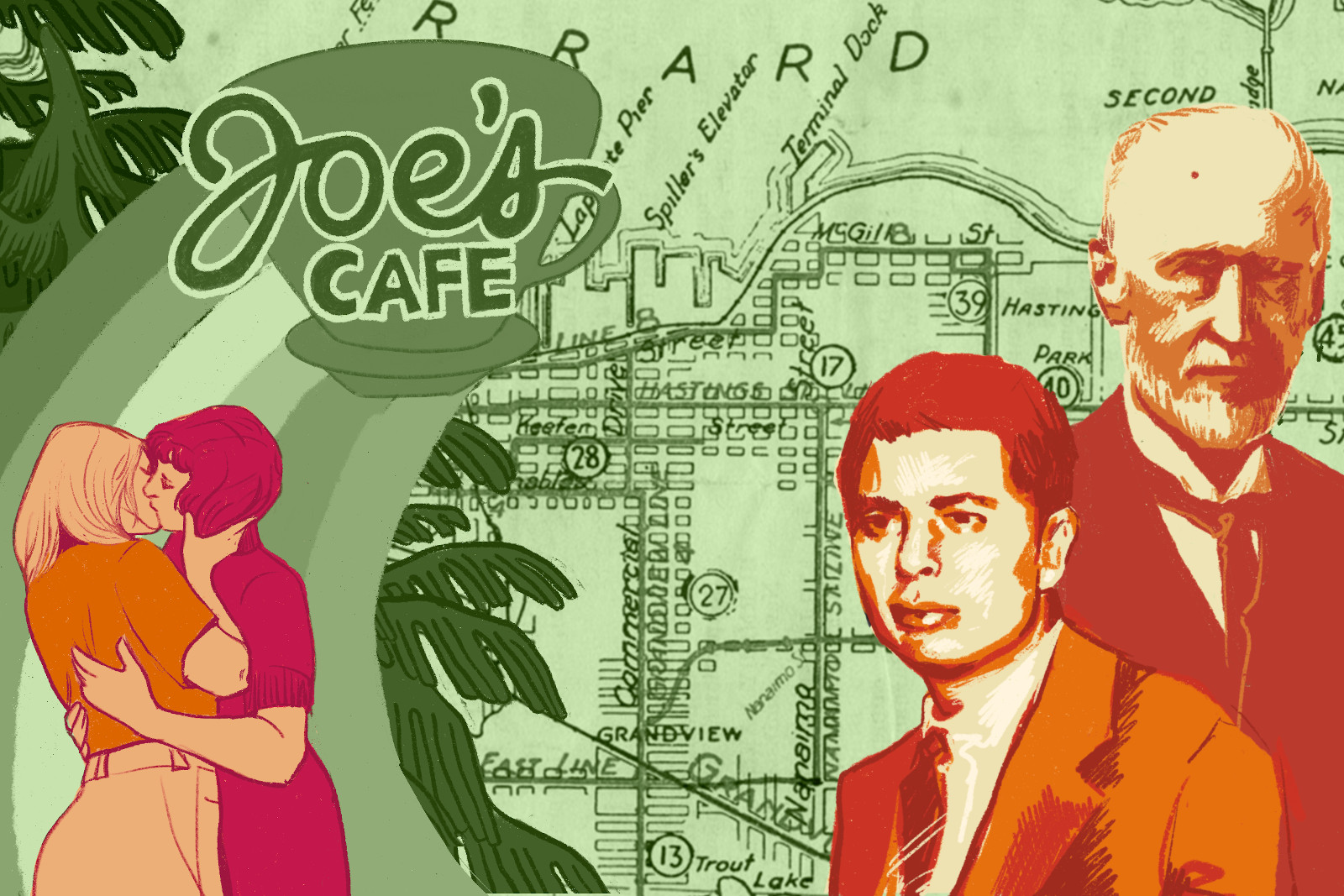

Although there are partisans for Caffe Calabria and Turk’s, it’s Joe’s Cafe, with its pool hall and old men sitting outside in folding chairs under awnings painted with the colours of the Portuguese flag, that is the iconic Drive coffeehouse. Joe’s, alongside the Portuguese Club of Vancouver, is the best spot in town to root for the Portuguese and Brazilian sides during the World Cup.

Charles Demers describes the Drive’s three big groups as “the Italians, the Lesbians, and the Leftists,” the last of whom have congregated, over the years, at Grandview Park, People’s Co-op Bookstore, and the now-defunct La Quena Coffeehouse, which was founded by exiles from August Pinochet’s Chile. These groups coexist peacefully, except when they don’t. On September 16, 1990, the sight of two women kissing at Joe’s Cafe enraged the owner so much he kicked them out. According to James Loewen, protesters “picketed the café. They staged a kiss-in. They mooned customers.” Loewen also quotes Harry Grunsky: “Some hetero guys who worked for Joe quit over the incident.” Grunsky, a former president of the neighbourhood area council, went on to open Harry’s, a competing and proudly LGBTQ-friendly Drive coffee shop off Charles Street in the nineties.

Due to its heritage architecture and the city’s unfriendliness toward those without intergenerational wealth, the Drive and its long-lingering subpopulations now face existential threat from moneyed yuppies, as the area grows whiter and richer. In a short story from Zsuzsi Gartner’s 2011 collection Better Living Through Plastic Explosives, the protagonist, a longtime Drive resident, muses that after “a period of intense gentrification, a mini baby boom, and the opening of three overpriced florists and a string of restaurants with daily fresh sheets listing boutique beers, there was a sense of emptying out. Her friends … fled to the suburbs where they had sworn they’d never go.” Recently, local activists, including members of the Grandview Heritage Group, have fought against city plans to build a trio of residential towers by the SkyTrain station on Broadway.

Still, welcoming community events such as Italian Days, Car-Free Days, and the Parade of Lost Souls bring out the best in the neighbourhood, a thoroughfare built for logging trucks and streetcars, and updated for commuters and cars, that is still best experienced on foot.