Before Eve Lazarus started work on Murder by Milkshake, she had very little desire to explore the story of Rene Castellani.

“The story found me,” she recalls. “I had no interest in writing about it. I found it interesting, because I’ve always been fascinated with the forensics side of things, but it wasn’t a book. Or so I thought.”

And Lazarus had good reason to be hesitant; the events surrounding one of Vancouver’s most infamous homicides have been written about extensively in the 50 years since they first took place—the tale of a charismatic, sociopathic radio personality convicted of slowly poisoning his wife Esther in the final years of the 1960s. But a meeting at the launch of Lazarus’s last book, Blood, Sweat and Fear, changed her mind. The story did indeed find her, in the form of Castellani’s daughter Jeannine: 11 at the time of the murder, and now a mother of two, she came forward with a unique perspective on the case.

Esther, Rene, and Jeannine Castellani with Cocoa, circa 1964. Photograph courtesy of Jeannine.

“I worked with her all the way through this book,” Lazarus notes. “I found it such a compelling story from her point of view—and Esther’s. Esther’s story has really been hidden in all of this, because Rene was such a bizarre, over-the-top guy that everyone wanted to write about him. I wanted to give her a voice, and Jeannine was able to help me do that.”

The result is a book that is at turns heartbreaking and harrowing, maximizing the Vancouver-based writer and historian’s skills as a researcher and interviewer to chronicle the story of the Castellani family in intimate detail—Jeannine’s childhood, Rene’s affair with CKNW secretary Lolly Miller, and the often-gruesome details of Esther’s murder as, over the course of two years, her husband spiked her vanilla milkshakes with increasing doses of arsenic.

“I shared an early draft with Heather Burke, a forensic psychologist who works with prisoners,” Lazarus says. “And she was able to read it and say, ‘God, this guy ticks off every box on the psychopath checklist.’ He was charming, he was manipulative, he was smart. And he didn’t let anyone get in his way.”

Castellani and Esther were married at 21 in Holy Rosary Cathedral, with a reception in Stanley Park. Castellani worked alongside legendary street photographer Foncie Pulice, and later began appearing as a guest on Jack Cullen’s hit CKNW radio show Owl Prowl; alongside Cullen, Castellani covered the infamous Beatles concert at Empire Stadium. By all accounts, Castellani was a charismatic man, a gifted singer and performer; and despite an unhappy childhood, Esther was described as a positive, upbeat woman with a winning laugh.

During Jeannine’s childhood, Castellani worked a variety of odd jobs such as washing machine repairman, and became embroiled in several get-rich-quick schemes that failed spectacularly and expensively. Eventually, he began work at CKNW doing live sketches (often with Cullen), the most well-known of which was a Jerky-Boys-style prank-call series named “The Dizzy Dialer.” It was at CKNW that he met Adelaine Anne “Lolly” Miller. She was recently widowed, and the two quickly began an affair—one that was not only obvious to everyone at the station, but eventually to Esther as well. Then, in late 1964, after finding a letter from Miller addressed to Castellani, Esther confronted her husband. And shortly afterward, as Lazarus writes, Esther began to experience stomach problems.

Lolly Miller after the inquest into the death of Esther Castellani. Photograph by Dan Scott, courtesy of the Vancouver Sun, December 1966.

“When Esther first started getting sick, it was when she first found out about the affair,” Lazarus says. “Heather [Burke] thinks it wasn’t to kill her at first, it was just to keep her from nagging him when he’d go to see Lolly. But over, time, he kept getting away with it, and this just made him more and more emboldened.”

In the beginning, friends didn’t see a problem, because Esther had a terrible diet, smoked excessively, and drank far too much coffee. She saw several doctors, but they couldn’t find any discernible reason for her gastric distress. In the meantime, Castellani and Miller’s affair carried on; in fact, both were disciplined by station management and threatened with termination if it continued. Around this time, Castellani began to discuss an impending divorce from Esther among a select few friends. But, as Lazarus explains, in the world of the late 1960s, this wasn’t a simple process.

“I always wanted to know why he didn’t just divorce her,” she muses. “But it turns out, divorce was really difficult until 1968—if you were a woman in particular. You had to prove adultery, but you also had to prove bestiality, or domestic violence, or incest. And it was published in the papers. You were publicly shamed, alongside the name of the person you were having the affair with. So, for someone like Rene, who was very likely a sociopath, a divorce would have been seen as tawdry, and tarnish the image he had of himself. He wanted to get rid of his plump, 40-year-old wife, and trade her in for a 25-year-old with money.”

But as Castellani discovered, getting rid of Esther wasn’t going to be that easy—it would take careful planning. By now, he was giving his wife regular doses of arsenic (a colourless, tasteless, easily accessible poison), often added to her White Spot vanilla milkshakes. By early 1965, Castellani had increased the dosage, and consequently, Esther’s condition deteriorated. Her stomach pains began to extend into her lower back. She spent entire days vomiting, and her hands began to go numb. Esther was now seeing two different doctors, neither of whom was getting to the bottom of her health problems but suspected they were the result of either an inflamed gallbladder or gastroenteritis.

Eventually Esther was admitted to Vancouver General Hospital and put under the care of Dr. Bernard Moscovitch. During that time, Castellani was a regular fixture at the hospital, bringing her fluids, often in the form of the vanilla milkshakes she liked so much. And although Moscovitch conducted a battery of tests, including blood work, x-rays, and an electrocardiogram, the possibility of poison didn’t occur to him until much too late.

“Every doctor who was looking at Esther said, ‘It didn’t occur to us,’” Lazarus notes. “They didn’t know he was having an affair. He was playing the role of the doting husband. They were all going, ‘Oh, he’s so nice. He’s showing up late at night to attend his wife.’”

During Castellani’s most noteworthy stunt, called “Guy in the Sky” (an auto promotion during which he stayed in a car on top of the iconic BowMac Sign on Broadway until every vehicle on the lot was sold), Esther’s health improved. But once Castellani returned, so did Esther’s symptoms. By now, her hands and feet were completely numb. She couldn’t keep water down. She had a blister-like rash all over her body, and she found even the lightest touch painful. By late June, Esther’s condition had worsened so drastically that she had to be put on oxygen. By early July, she was dead.

During this time, Castellani had displayed a remarkable lack of empathy for his dying wife. He had begun house-hunting with Miller, and even signed paperwork for a mortgage that claimed they were married. He had given Miller Esther’s fur coat. And the day after his wife’s funeral, he took Jeannine, Miller, and Miller’s son Don on a trip to Disneyland. Dr. Moscovitch, who had by then been treating Esther for almost two months, requested an autopsy. At first Castellani refused, but after consultation with CKNW station manager Bill Hughes and longtime friend Frank Iaci, he changed his tune.

“If he hadn’t given permission, he would have gotten away with it,” Lazarus explains. “If he’d had the body cremated, he would have gotten away with it. Had he gotten rid of the arsenic under his kitchen sink, he probably would have gotten away with it. But I guess he thought, ‘Oh, well. I guess I’ve gotten away with everything else.’”

Then, as now, arsenic tests aren’t routine during an autopsy, and at first, the compound went undetected. Unfortunately for Castellani, Moscovitch wasn’t willing to let it go. “He went through all the case notes,” Lazarus continues, “and he realized, ‘Oh, my God. Arsenic mimics gastroenteritis, and all of these others symptoms she was having.’ And that’s the beauty of arsenic; it’s a pretty perfect way to kill someone.”

A second autopsy found that Esther’s liver contained arsenic concentrations 1,500 times higher than normal, and that there were concentrations 800 times above average in her heart. The case was officially declared a homicide, and once police began their interviews, Castellani became their prime suspect. The investigation itself didn’t last long; after word of his affair with Miller was confirmed and a box of Ortho-Triox (a weed-killer containing high levels of arsenic) was found under his sink, Castellani was arrested and charged with capital murder. Although the evidence presented was largely circumstantial, it didn’t prevent two different juries from sentencing him to death. And during the process, Jeannine—then 13—was made to take the stand in her father’s defence.

“She was put on the stand when she was 13 years old and told what to say,” says Lazarus. “And 50-odd years later, I’m reading her the testimony from the trial and going, ‘Is this true?’ And she kept saying, ‘No, that didn’t happen. I was told to say that.’ Because she believed him right until she was in her early twenties. She believed that he was innocent. She was a 13-year-old girl, and she had no one. She would have done anything to keep him out of jail, and he was very manipulative.”

After the sentencing, Jeannine spent about five years living with Miller and Don—a situation that ended when Miller met someone new and pawned the teenager off on an aunt. In the meantime, Castellani had caught a lucky break: two weeks before his date with the gallows, Canada temporarily suspended the death penalty and commuted his case to life imprisonment. Within two years, he was doing community service playing Santa Claus in Abbotsford. Within five, he had weekend passes. Within 10 years, he was fully paroled and working at a radio station.

Castellani died in January 1982. By then, Jeannine, who had come to recognize her father’s guilt, had long since cut off all contact—though she did attempt to visit him on his deathbed, in hopes of extracting a confession. Today, in interviews with Lazarus, she contends that “he should have been hanged for what he did.” However, Lazarus says, for all its talk of Castellani’s sordid past, Murder by Milkshake is a book that also yielded positive benefits in the present. “It brought Don and Jeannine back together after 50 years,” she notes. “They’d lived together as brother and sister for almost five years. But after that, they had no idea. It was never talked about again. He had always wondered what had happened, and so had she. Now, they and their families are connected. They do Christmas together. And I thought, ‘Wow. That’s huge. It’s something other than just a book. It’s impacted people’s lives.’”

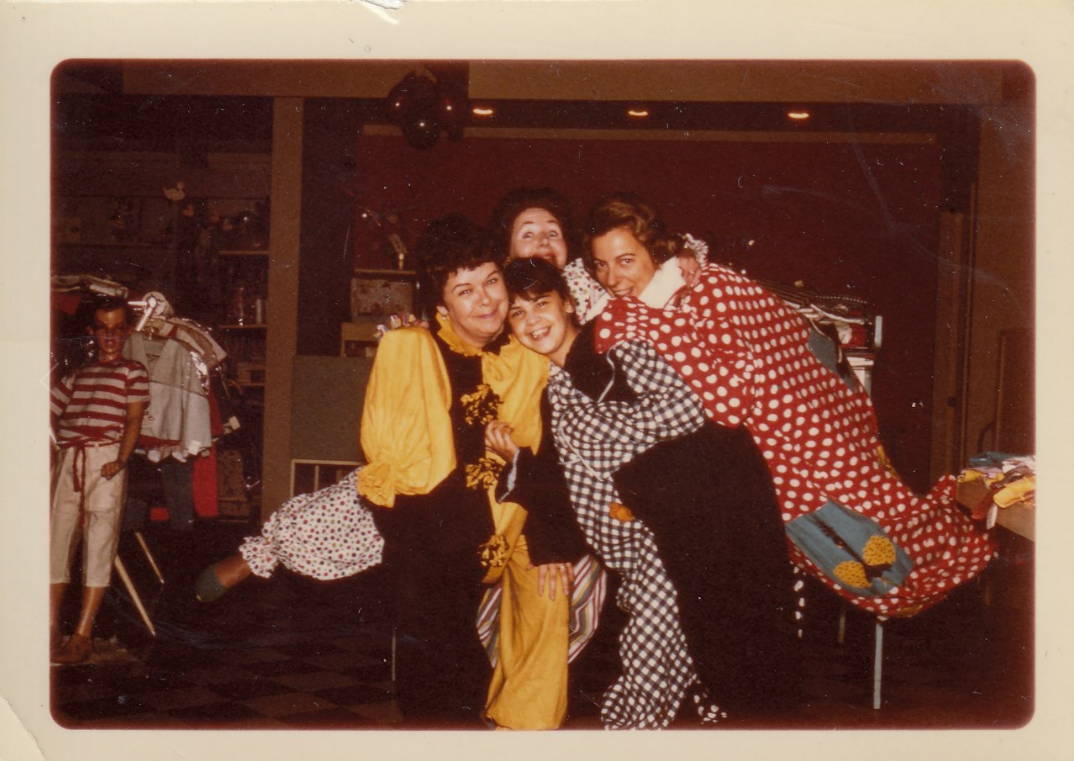

Clowning around at Joyce Dayton’s Children’s Boutique in Kerrisdale. Esther, Jeannine, Joyce, and Freda (at back) circa 1963. Photograph courtesy of Jeannine.

In the end, for Lazarus, it was one of those people’s perspectives that mattered more than any other. “When I sent Jeannine the manuscript, I started freaking out a bit,” she says with a chuckle. “I wondered, ‘What if she hates it?’ It’s no-holds-barred. She hasn’t talked about this in over 50 years, and suddenly everything is out there. I was worried what she was going to think. But when it was over, she said, ‘Now I’ve finally had a chance to grieve my mother.’”

This article from our archives was first published on November 21, 2018. Read more stories of Hidden Vancouver.