On September 8, 1911, as the Empress of Ireland slid away from the Mersey quayside, the Union Jack and CPR flag fluttering overhead, a 32-year-old tailor named Helena Gutteridge took leave of England, travelling second class with 10 dollars in her pocket. She had short, dark wavy hair and a striking serious face—a stranger once asked her on a bus if he could sketch her mouth for inclusion in a painting he was working on. When asked if she intended to stay in Canada permanently she lied and said “Yes.”

In fact, Gutteridge was something of a missionary. A veteran of London’s women’s suffrage movement, she had given speeches on a soapbox at Hyde Park and joined a pitched battle with police in front of Westminster Abbey where she was arrested along with 115 other women and four men. Disillusioned with the growing violent tactics and hierarchical leadership within the suffrage movement, and its dismissal of working-class women like herself, Gutteridge was now on her way to Canada for what she intended to be a four-year mission to bring the gospel of women’s suffrage to the colonies.

Gutteridge would, however, spend the rest of her remarkable career in Canada, fighting for women voters in British Columbia, winning a seat as Vancouver’s first woman city councillor, igniting a social housing movement, and building the British Columbian arm of the Co-Operative Commonwealth Federation, the precursor to today’s NDP.

The story of Helena Gutteridge is a valuable reminder of the true origins of International Women’s Day. Today, the yearly celebration on March 8 is embraced by governments, the United Nations, skincare brands, and fast food chains. But the history of the day is not just about recognizing powerful women, or even celebrating womens’ right to vote; International Women’s Day is the story of a long, difficult struggle for legal rights but also housing, equal pay, health care, and dignity.

Helena Gutteridge in 1911, the year she arrived in Vancouver.

International Women’s Day began with a protest, but exactly which one is up for debate. One common story places the origin in 1908, when 15,000 women, members of the Socialist Party of America, took to the streets of New York City to demand better working conditions, higher wages, and the right to vote. A year later, in 1909 the same group declared a National Women’s Day in the United States. Some historians theorise the 1908 march was itself to honour the anniversary of another march by textile workers 50 years earlier, while others argue that this story was invented later to separate the day from its socialist roots.

In 1910, Clara Zetkin advocated for a Women’s Day at a Conference of Working Women in Denmark, which unanimously agreed. The following year the day was recognized in Austria, Denmark, Germany and Switzerland, with over a million women rallying on March 19 for the right to work, vote, be trained, and hold public office. A week later the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City took the lives of more than 140 working women, most of them Italian and Jewish immigrants. The disaster raised scrutiny of working conditions and labour legislation, which became a focus of future Women’s Day events.

The March 8 date of Women’s Day may have arisen from a group of Russian women, led by feminist Alexandra Kollontai, who went on a four day strike demanding “bread, peace and the right to vote” on March 8, 1917. The strike set off a chain of events forcing the Czar to abdicate and igniting the Russian revolution, leading the provisional government to grant women the vote. Russia’s Communist Party later declared Woman’s Day an official Soviet holiday, with communists in Spain and China following suit.

Mrs. Susie Lane Clark and Alderwoman Helena Gutteridge examining a C.C.F. annual picnic brochure, 1938. Courtesy of the Vancouver Archives.

In British Columbia, many of the same ideas that drove the rise of International Women’s Day played out in the life of Helena Gutteridge. Her story, along with many of the details included in this article, is recorded in her biography The Struggle for Social Justice in British Columbia by Vancouver historian and English professor Irene Howard.

After arriving in Vancouver on September 21, 1911, an election day that saw Wilfrid Laurier defeated and replaced by Robert Bordon’s Conservatives, Gutteridge threw herself into organizing, at first for women’s suffrage but soon also for higher wages, employment, and better working conditions. In the years between her arrival and her final victory securing votes for women in British Columbia in 1917, she not only fought politically but also organized a toy and doll-making cooperative that employed hundreds of women.

With the vote won, Gutteridge was far from satisfied. While living and working for a decade on a poultry farm in Mount Lehman—present day Abbotsford—with her husband, she continued to organize for equal pay and workers’ rights for women. After separating from her husband, she returned to Vancouver and joined the nascent CCF. In 1937, she became the first woman elected to Vancouver City Council, where she fought for married womens’ right to work and formed a committee to tackle the growing problem of unaffordable housing in the city.

She served on the city council until she was defeated in 1939, possibly because she objected to the city paying for a visit from King George VI when the money could be better used to help the poor (despite being a committed monarchist, she was quoted in the paper as saying that Vancouverites “shouldn’t be responsible for putting on a circus from which others benefit.”)

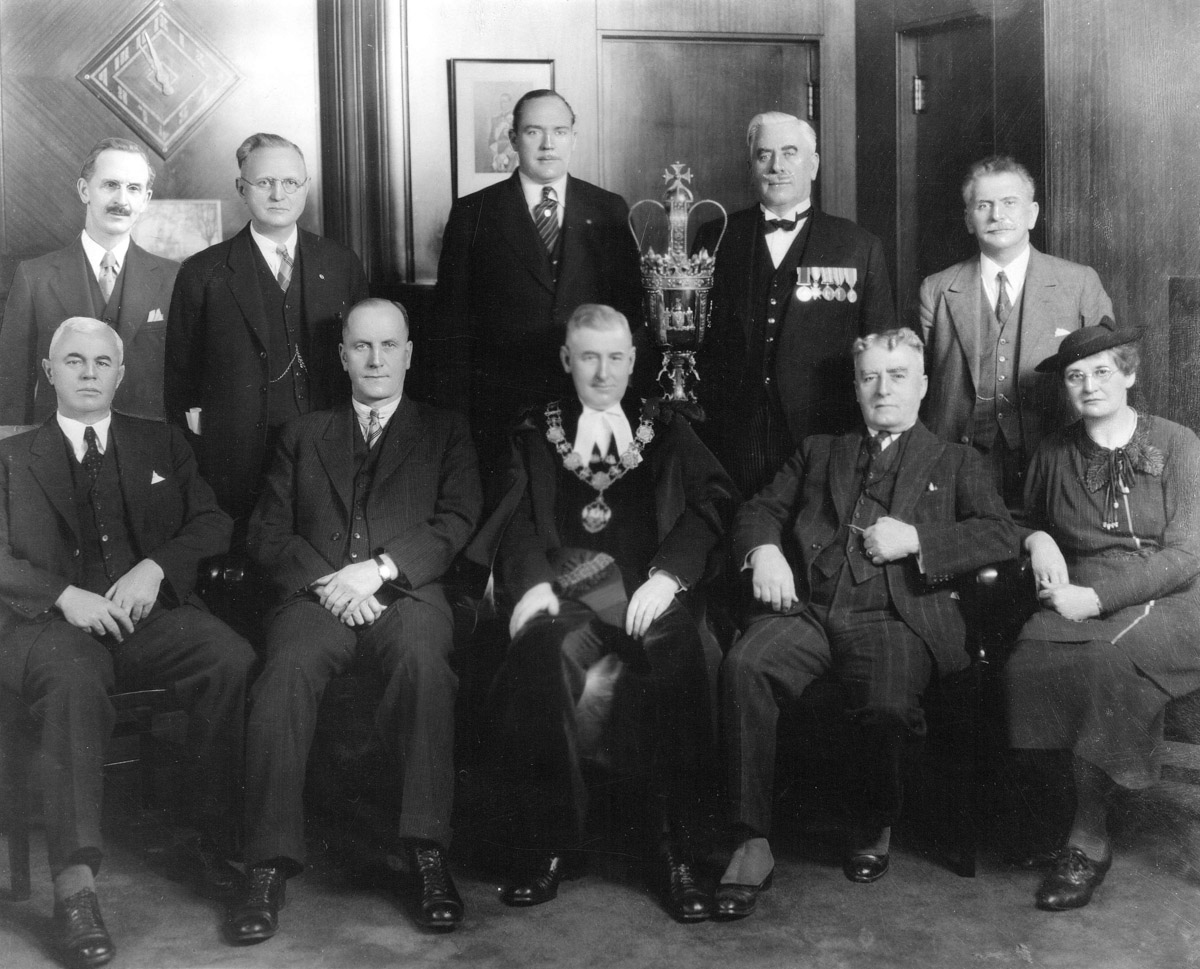

Gutteridge with the city council in the mayor’s office, 1937. Courtesy of the Vancouver Archives.

Like many suffragettes of her time, Gutteridge at first prioritized the rights of white women over Asian and other non-white people. In her later life, and with exposure to anti-racist activism in the CCF, however, her attitudes shifted. By the outbreak of the Second World War, she was fighting city councillors to defend the rights of Asian Canadians to hold business licences. After leaving city council, she finished her career as a welfare worker with the interned Japanese population at Lemon Creek.

Gutteridge’s outlook is well represented in a column she wrote in August 1918, a year after white women had won the right to vote in British Columbia, and a few months after they had won the vote federally. She bemoans how, after the long fight for women’s suffrage, many now expected women to vote as a unified block to solve all of society’s problems. Women, she argued, were a diverse group with diverse needs and interests, just like men, and it would take education as well as economic and social change to fully empower them.

“The general condition of society at any time is determined by the economic structure of society, and if a permanent change is desired, then the economic structure of society must be changed. We cannot expect freedom and democracy, if the economic basis of society is founded on human slavery,” she writes. “If a sane reconstruction of human society, together with the abolition of war, it will need the votes of an educated public opinion in the majority, of both men and women.”

Until 1975 when the United Nations officially recognized International Women’s Day, the holiday was primarily celebrated in socialist countries. Since then, however, it has grown in popularity and recognition, with the UN releasing a yearly theme from 1996 (“Celebrating the past, Planning for the Future”) to this year (“Gender equality today for a sustainable tomorrow”). Today it is recognized all over the world, often as a day to recognize the accomplishments and contributions of women to society. The stories of campaigners like Helena Gutteridge, however, are a reminder that International Women’s Day was first a rallying cry by working women for equality, fair wages, and the right to bread and peace.