From 911 operator to air traffic controller to high school principal, the jobs that form the backbone of our country share the spotlight in How Canada Works: The People Who Make Our Nation Thrive, a new book of illuminating first-person stories collected by Peter Mansbridge and Mark Bulgutch.

So you think your job is challenging? Spare a moment for Craig Houghton. He’s the principal of the Fort St. James Secondary School in north central British Columbia. His is no easy job. But just like school principals in big cities and small towns across the country, Craig helps make the country work by leading a team that fosters the next generation.

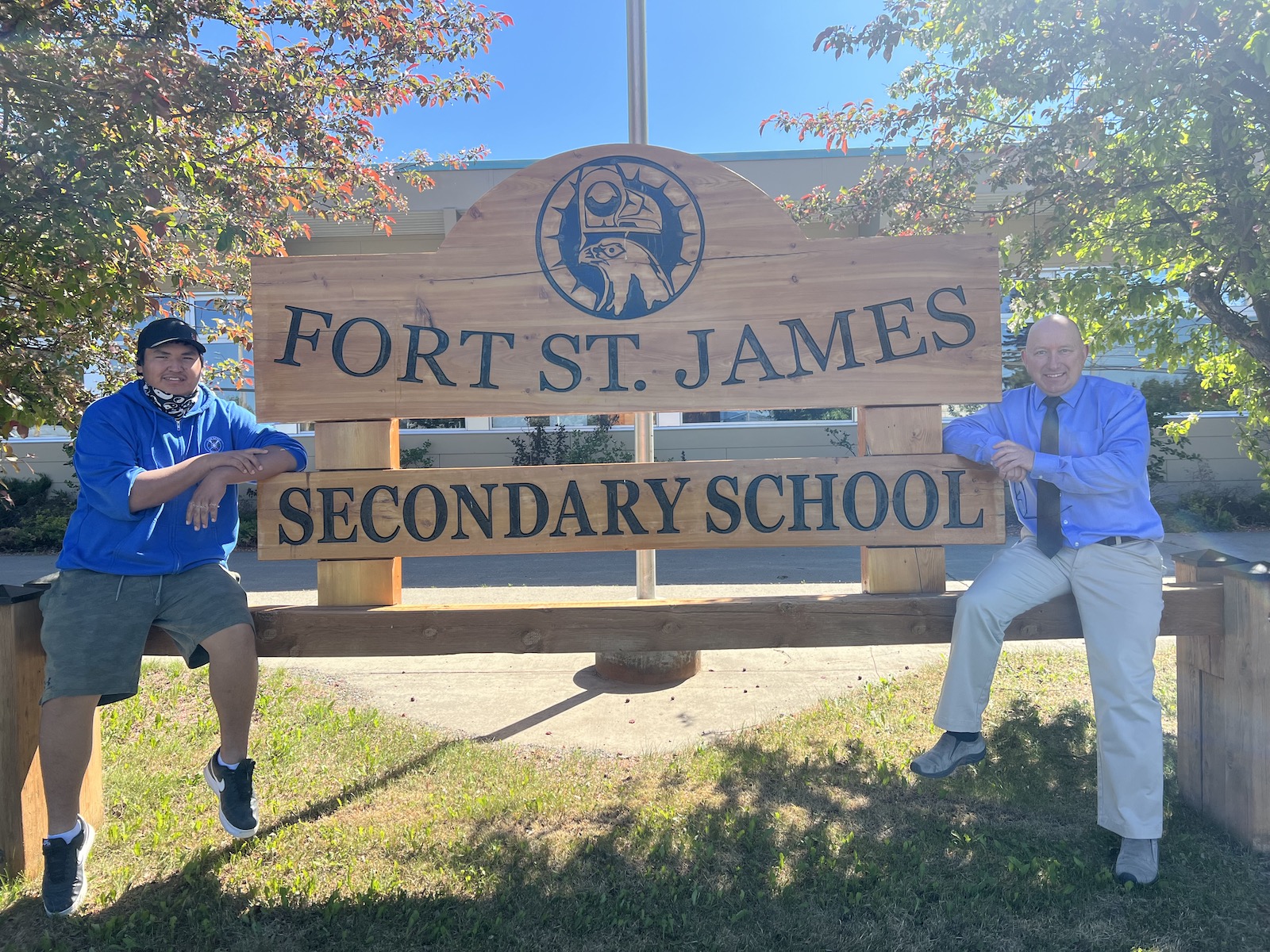

The Principal: Craig Houghton

When you’re the high school principal in a small town, you become a community leader by default. That’s because the school isn’t just a school. It’s a gathering place for the community.

Situated on Stuart Lake, our town of Fort St. James is a former fur trading post about a two-hour drive northwest of Prince George, British Columbia. Many of the more than 1,300 people who call this place home work at one of the major sawmills in the area, and their kids attend our school, Fort St. James Secondary School, which has also become the rec centre for the community. It’s hosted wedding receptions and even funerals too. And when we have wildfires in the area—which is often in north central BC—the school becomes a haven for people who are forced from their homes. So I’m here working all the time. I’ve got to be.

Fortunately, I know my way around these halls because I was once a student here myself. My father also taught at this school for many years. I knew I wanted to be a teacher too, so after I studied at the University of Victoria for six years, I came back to northern BC to teach at Eugene Joseph, an on-reserve, band-operated elementary school serving the Tl’azt’en First Nation community. Later, I returned to Fort St. James Secondary as a teacher, and then in 2013, I was made principal.

At that time, the school had a low ranking in the province according to the Fraser Institute, a nonpartisan research organization. But they’re looking at straight academics, and while those are important, I look at a number of other factors. One being the resources available to us as a small school. And two being the individual student’s progress when it comes to engaging with their studies and their peers.

In a small school, the timetable reflects what we value most. There are only so many minutes to work with. There are only a certain number of teachers, and they have certain talents. For example, I may want to have a music program, and the parent advisory committee may want a music program, but if I don’t have a music teacher or the money to hire one, then we have to focus our efforts elsewhere. For the size of our school, we have a phenomenal athletic program because we have a passionate athletic teacher who’s really good at motivating students. About 44 percent of our kids are directly involved in school sports, and on top of that, we have more kids involved in refereeing or scorekeeping and those kinds of things.

That’s the nature of a small school. We can’t be great at everything, but we can be great at certain things.

“Here I am with Javon Felix, one of our 2023 shop class students who loves woodworking, in front of our school sign, which was made by a group of our students.”

As the principal, I try to be as innovative as possible, and while academics are important, I support programs that prepare our students to contribute in a meaningful way to day-to-day life in BC. For example, we have a small sawmill at the school, and we get wood for the students to cut and make things with. We also have a metal shop and an automotive shop. We have a firefighting program too, where students can train at our local fire hall and go out on real calls. I’ve seen cases where three people have gone to a house fire. One is an adult and the other two are my grade-11 students.

We also have a grade-12 class that combines environmental studies and geography, where the kids do a lot of learning on the land at a research centre about half an hour away. The centre partners with one of the local First Nations and the University of Northern British Columbia and allows our students to work with professors who may be researching hummingbirds or pine martens, giving them an incredible opportunity.

When it comes to our students’ progress, I take into account where our students are starting from and what they might be facing. For example, around two-thirds of our 270 students come from one of the four First Nations located along the lake, and I work very closely with the bands to ensure that we’re providing Indigenous kids with the same opportunities as all the other kids.

What I’ve learned is that when grandparents come in, I need to listen. They are there to talk about their grandchild, but often they get to talking about their own lives, and I’m humbled by what they have endured.

In speaking with the bands, I’ve heard firsthand how the parents want their kids to do well. Some have had bad experiences in public school themselves, and as a result, aren’t necessarily able to tell their kids what it takes to be successful academically. Others may be dealing with substance abuse or in and out of jail. Many of our kids are being raised by grandparents who may have survived a residential school, and so sometimes, the grandparents are nervous about coming to our school. I’m not a big man—I’m 5′ 6″—but I recognize that as a white guy with a tie, I might make them uncomfortable. I do my best to address that. What I’ve learned is that when grandparents come in, I need to listen. They are there to talk about their grandchild, but often they get to talking about their own lives, and I’m humbled by what they have endured. Their grandkid may be acting out or falling behind, and the teachers may be at their wits’ end, but when I hear what the family is going through and how they are trying to help their grandchild, I feel for them.

And then I try to come up with a very specific plan for that student, whether that’s seeing a counsellor or making a homework schedule. I might say, “Block one is math. Block two is history. And so on.” In two weeks, we can go over what’s been happening, hour by hour. It’s a good exercise for everyone to see how the student’s time is spent. Do they need more sleep? Do they need to block off more time for homework? And how can the school and the family work together to make those things happen?

These are the cultural nuances that we need to be mindful of if we’re to truly bring about reconciliation. Because the federal government funds education for Indigenous kids who live on reserves, the bands contract us to teach those children. Given the historic relationship between government educators and Indigenous communities, the bands are very watchful. They want to make sure there’s no systemic racism. They want to make sure their kids are being treated equally. And they’re right to have these concerns.

There’s no doubt in my mind that twenty-five years ago, we had systemic racism at the school. I know that for a fact. I was part of it. I was part of the system. But now I’m part of the system to change things for the better. Reconciliation isn’t just a word. It’s action.

Take, for example, our senior girls’ soccer team. After we have try-outs for the team, I look at who made the team and who didn’t. And I ask, do we have a fair representation of First Nations and non–First Nations? And if we don’t, I ask why. I want to be sure we’re giving everyone a fair chance to succeed.

The First Nations community has been vocal and said, “That’s not okay anymore.” And it isn’t. So, we’re making progress. The town is changing, the province is changing, and the country is changing with regard to how we treat First Nations people. For me, that starts at our school, and it starts by meeting the students where they’re at.

We do our absolute best to hire as many Indigenous people as possible at the school. We have only one First Nations certified teacher, but we also have learning-support workers from the community to assist the teachers. And we have a great system of bringing in knowledge holders, elders, and hereditary chiefs to work with our kids.

The hardest part of my job is trying to motivate our students. We see kids who are playing video games or watching Netflix all night. In the morning, they get on the school bus, and they arrive at school exhausted. We also have children from very traumatic homes, who find it hard to come to school and get excited about it. When that happens, we let them go to what we call our calming room, where there are some couches and food. We don’t ask why they’re there; we just invite them to sit, release some anxiety, get themselves together before they go to class.

One of our youth workers created a critical food program so every person in the school gets free breakfast every day, and if they need it, a free lunch too. Any time during the day, they can get bagels, toast, cheese, and a variety of fruit. That’s part of our caring process and how we help the kids in our community.

And I think the students understand we’re here to protect them because they protect the school. Fort St. James has some crime, but we have almost no vandalism at school. Sometimes a student will have a bit of a temper tantrum and punch a window or a wall, but generally in the summer and on the weekends, this place is not targeted.

We’re never going to be like every other high school in the province. That’s just the way it is. We can’t have stuck-in-the-box thinking.

So what the Fraser Institute doesn’t see is the gains that the kids have made from grade 8 to grade 12. They don’t see the kid who arrives here with his hoodie over his head and is afraid to look at you. Or the kid who has substance abuse issues. Or the unfortunate fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Or those with learning disabilities. They don’t see that. They don’t see the poverty, the intergenerational trauma, the isolation. When a student has all that working against them, we can’t pretend they’re like every other student in the province. But it doesn’t mean they can’t be successful in life.

We’re never going to be like every other high school in the province. That’s just the way it is. We can’t have stuck-in-the-box thinking. We can’t be thinking that Vancouver does something one way, so we have to do it the same way. No, we have to meet the needs of the kids in front of us. Sometimes, that means going back to the basics. Because we can’t teach fractions to someone who doesn’t know their times tables. We have to build that knowledge in them so that when they reach grade 12, they can graduate with a legitimate diploma they’ve earned and the skills to do well.

Which is why every graduate is a success story for us, and really for everyone in town. Our graduation ceremony is important. It’s a community weekend celebration. We have a formal ceremony in the gym on Friday night, where the grads walk up in their caps and gowns and get their diplomas. Then on Saturday, they dress up in nice clothes and parade through the town. Everyone comes out to see them. Fort St. James comes to a standstill because it’s grad weekend.

We’re proud that almost everyone does graduate. We find that many of our students take six years instead of the standard five years, but then 95 percent of all our students earn a diploma.

Over the years, we have had some wonderful success stories. Two years ago, we had a First Nations kid from one of the outlying communities who loved to play basketball. He had family support, but not what you would see in a larger town or city, where a parent can drive him around and pay for him to be in tournaments. This kid found a place to stay in town so he wouldn’t have to ride the school bus every day and could play basketball. He worked hard, became the class valedictorian, and went off to a college in Manitoba.

But the reality is, sometimes the kids break your heart. We work so hard with these kids, and we think they’re excelling, and then in a year or two later, we might see one downtown asking for money, sometimes drunk or under the influence. That’s hard. Because I know they have potential. I know they’re capable of so much more.

Do I blame myself? Partially, yes. I’m not perfect. I have lots of flaws. But our school is all about opportunity. We try to open doors for kids who have not seen too many open doors. And that’s all I can continue to do. Because it’s personal for me. I’m part of this community and I know all the kids by name. I’ve even taught some of the parents. I know most of their families and they know me, so I would never go to a larger centre because this is my home, and I want to do what I can to make it a better place.

Excerpted from How Canada Works: The People Who Make Our Nation Thrive by Peter Mansbridge and Mark Bulgutch. Excerpted by permission of Simon & Schuster Canada. All rights reserved. Read more stories about community.