There’s a reason why Major James Skitt Matthews has been dubbed The Man Who Saved Vancouver.

Irascible, endlessly energetic, and passionate about his adopted hometown, Matthews not only wrote, interviewed, and collected the city’s past, but also terrorized decades of mayors and councils in the name of his self-appointed mission: establishing—and later expanding—its archives. As a result of his efforts, Vancouver was the first city in the country to have its own civic archives, and the breadth of what he collected provides an invaluable glimpse into the city’s growth, stretching all the way back to the mid-1860s.

“Every British Columbian owes James Skitt Matthews an incalculable debt,” writes historian Daphne Sleigh in The Man Who Saved Vancouver, her biography of the archivist. “Had it not been for his extraordinary interest and persistence in searching out any item relating to the earliest history of Vancouver (and peripherally other parts of the province as well), we would have a much less graphic picture of the unique period when the city was born.”

Born in Wales and raised in New Zealand, Matthews’s early life reads like something out of a turn-of-the-century dime novel. At 17, he was essentially abandoned by his parents; before he was 20, he had successfully courted the daughter of an aristocrat—much to the chagrin of both sets of parents. Matthews and his partner, Maud Boscawen, arrived in B.C. in 1898, and he soon talked the Canadian government into allowing them to be wed, despite the fact that he wasn’t yet of legal age (at that time, the age of majority was 21). They had three kids and began establishing a life together, but when the First World War broke out, Matthews enlisted in the military, for which he had always had a fascination; owing to his zeal, he swiftly rose to the rank of Major. During his single active deployment, outside the French city of Ypres, he was shot through the face while leading his company in taking a German trench, and had to be dragged a half-mile to safety. Due to the heavy number of casualties sustained during the battle, he didn’t receive medical attention for nearly five days, and as a result was left permanently deaf in his right ear. When he returned home, Maud announced she was leaving him, and in order to “convince” her otherwise, Matthews held her captive until she forced him to release her by going on a three-day hunger strike.

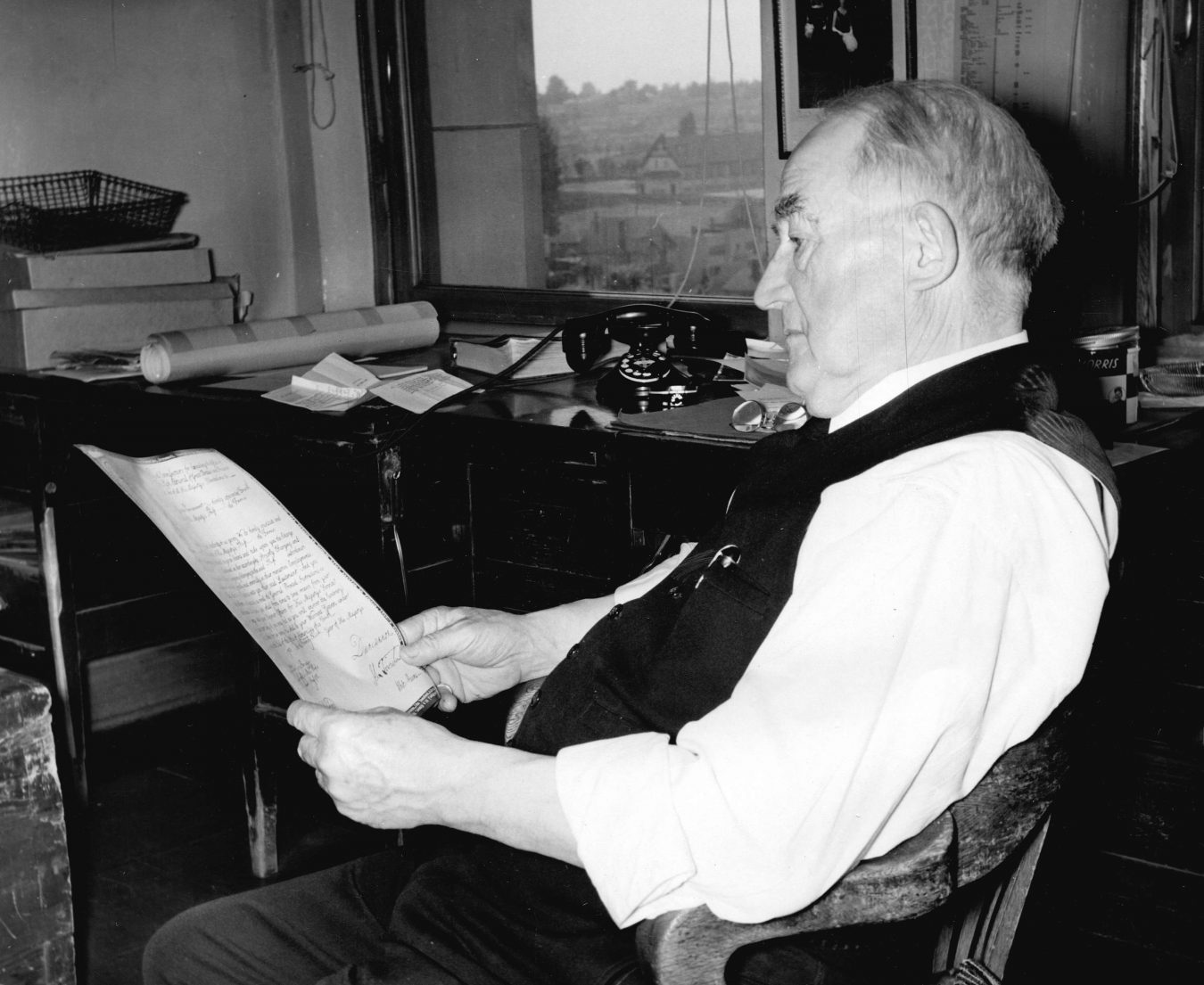

Matthews in 1961. Image Courtesy of the Vancouver Archives.

Despite his reputation as a gruff, cranky (and at times abusive) man, Matthews was also a guy ruled by his passions, and chief among those was the city of Vancouver. When he arrived here with Maud, he fell in love with it almost instantly, describing it in later writings as “the magic city” and “an earthly paradise.”

During his early years, he and Maud lived with their children in a variety of circumstances, spending time on a farm property in Fairview before settling on Pacific Boulevard, near the current foot of the Burrard Street Bridge. He worked as a clerk, and later as a district manager with Imperial Oil. By most accounts, he wasn’t the most dutiful husband or father, largely leaving Maud alone to mind the children while he indulged some of his other passions—in this case, history and the military. In 1903, his (uncredited) first piece about B.C. history appeared in the pages of the Vancouver Province. He became friendly with the paper’s staff, including its circulation manager, a man named LD Taylor; the friendship would prove particularly valuable in ensuing years (Taylor went on to become Vancouver’s most-elected mayor, known as much for his signature red tie as for his numerous corruption scandals).

One of Matthews’s earliest attempts at recording city history came on Armistice Day, 1918. Although he had dabbled in military history and begun to collect various random artifacts (which he stored in his basement), this was his first attempt to catalogue a place and time; when awoken in the night with the news of the peace accord, he sat at his desk for close to two hours to set the experience down for future generations. “I got up, and recorded for the benefit of those who follow me,” he later wrote, “the first impressions of one mind at the receipt of the news that the greatest of all wars had ended.”

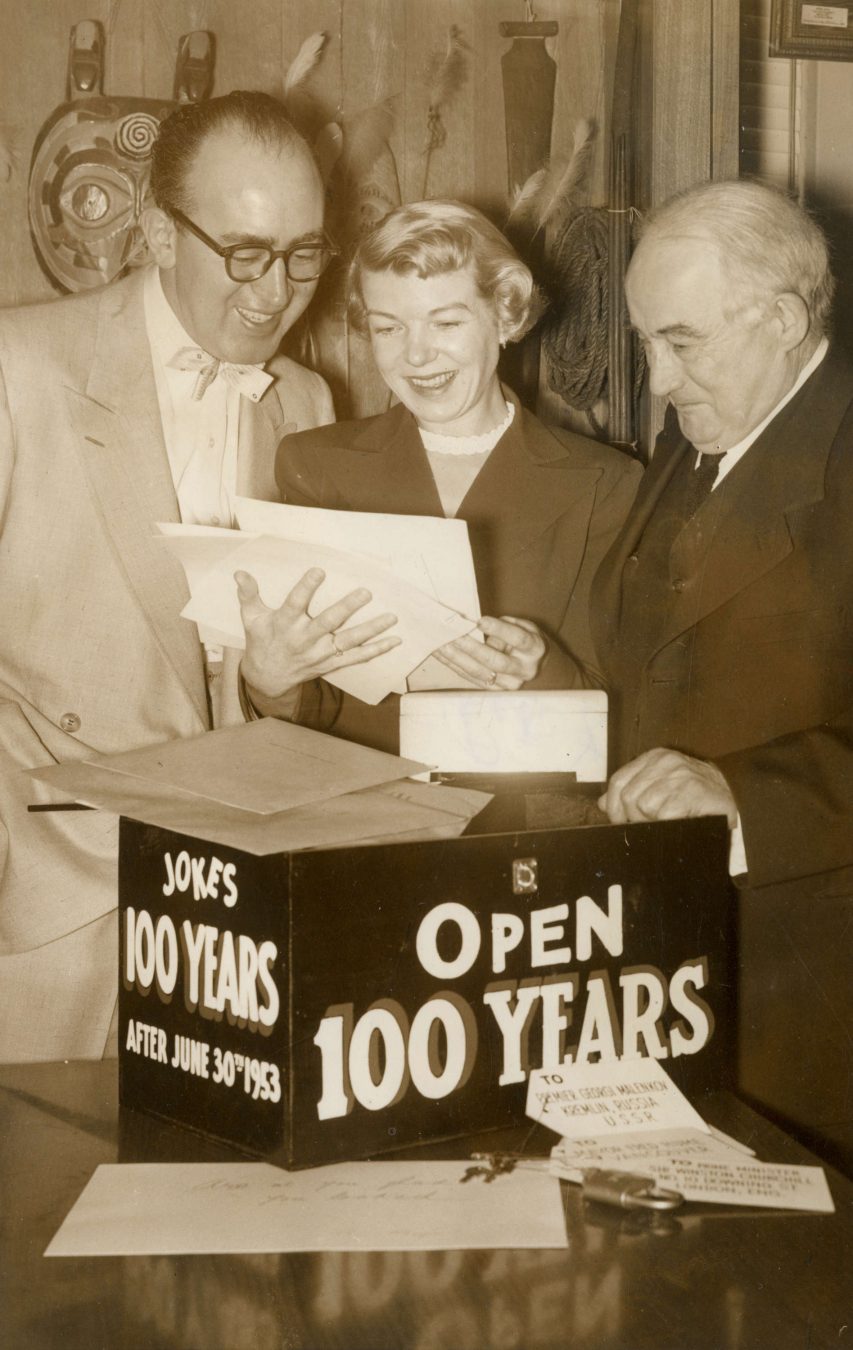

Matthews with Premier WAC Bennett and Mayor Tom Campbell, 1968. Image courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives.

At that point, collecting and recording city history was a hobby, but it wasn’t yet a vocation. In fact, while Matthews is remembered today as the city’s archivist, he didn’t find his calling until remarkably late in life. He spent the postwar years searching for direction; after his divorce from Maud, he sank into a deep depression, and while he had little aptitude for fatherhood, he had a deep, abiding friendship with one of his children: his son Hugh, who nursed his father through this trying period—made worse when Matthews discovered he had been demoted by Imperial Oil, from district manager to a lowly clerk.

“He was my helpmate, my friend, my companion, my advisor,” Matthews wrote of Hugh. “Together we lived in comfort and loneliness, doing all our own housekeeping in that big house, sleeping in the same bed, cooking our meals together.”

His life improved measurably after he met Emily Eliza Edwards, who would go on to become his second wife. The pair had first connected in 1902, when Matthews was admitted to Vancouver General Hospital with typhoid, and had established an easy rapport (Edwards being the only nurse in the building willing or able to manage his difficult personality). By the time they became reacquainted in 1919, she had gone on to a prestigious career in medicine, and served as a nurse during the war, earning a number of medals and commendations. They were married within a year at a military service at Christ Church Cathedral downtown.

The Matthews family in 1949. Image courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives.

But their happiness was only temporary. In 1921, just a year after the marriage, the family suffered what Matthews would later call the greatest loss “I have suffered, or ever shall suffer”: Hugh was involved in a fatal (and grisly) workplace accident, breaking his neck after his head became trapped between a freight elevator and the floor above.

“We had been chums almost from birth,” he lamented in writing. “I think he would have made a bright, clever, and good man. God bless his dear memory. Perhaps the Almighty in His infinite goodness had some good reason for taking him. His work perhaps was done. I have expressed gratitude many a time for having him spared to me for so many years.”

In 1923, Matthews lost his father, who lived in Wales. In 1926, he lost his mother, who, for reasons unknown, disinherited him of all but 200 British pounds. He quit Imperial Oil and spent time in charge of a tugboat company. In 1927, he finally dove into a project about which he was passionate: a history and genealogy of the Matthews family. And then, one morning, at the age of 50, while putting on his boots, he “suddenly ejaculated to Mrs Matthews: ‘I know what I’m to do.’” In 1929, he began the monumental task of organizing the historical artifacts that filled the basement of his Kitsilano home. In the same year, he began a regular correspondence with John Hosie, B.C.’s provincial archivist in Victoria. And then, not long afterward, he took his case to the government.

At Matthews’s urging, Hosie appealed to the province for funds to establish Vancouver as an arm of the provincial archives program. When this gambit failed, Matthews made a presentation to Vancouver City Council, where he passionately argued the merits of archives as unique as the city he had grown to love. Unfortunately, his timing was less than perfect. The stock market crash of 1929 had sent the world economy into a tailspin, unemployed workers were causing massive civil unrest, and civic governments were already being forced to cut services.

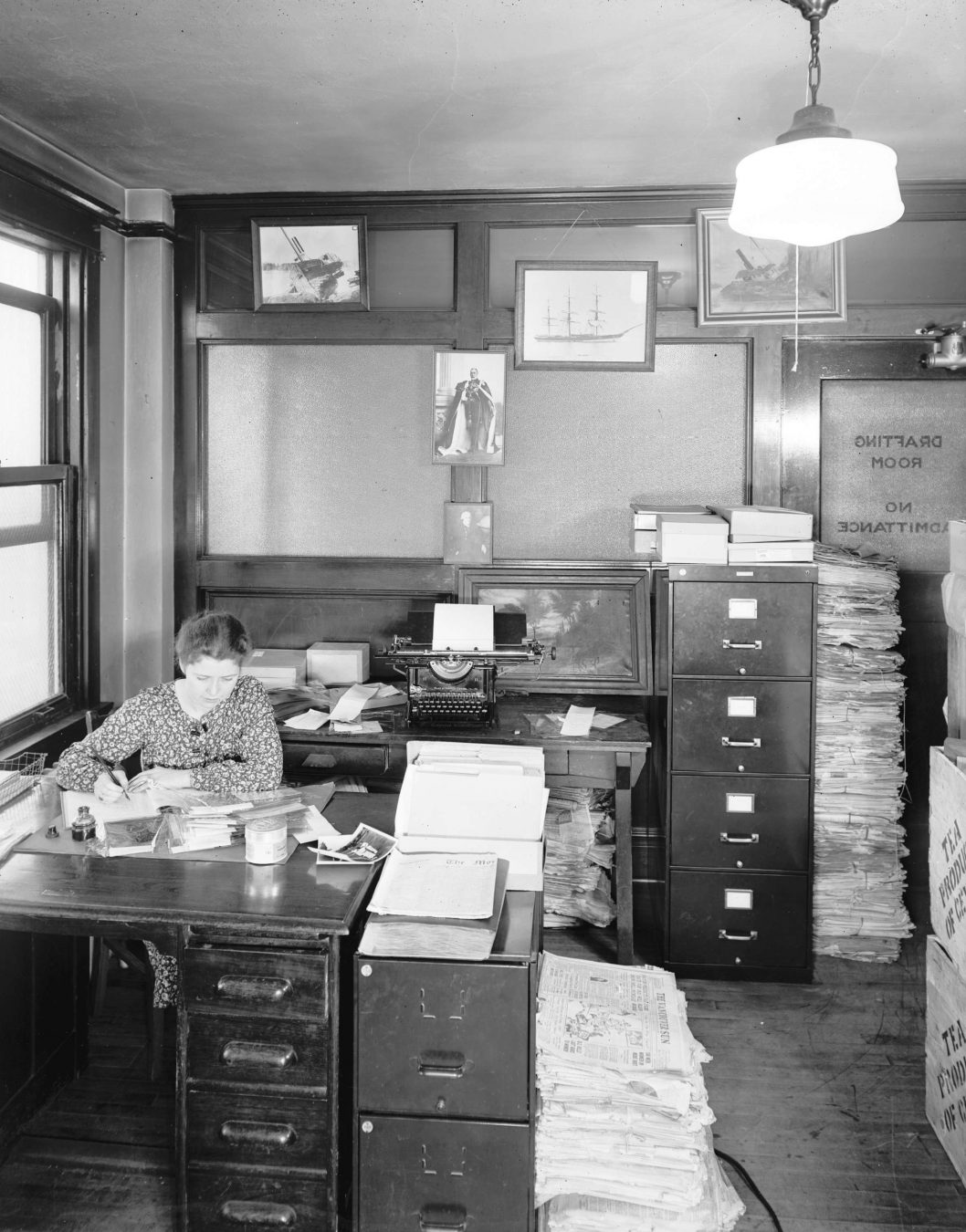

The first City Archives, 1931. Image courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives.

Luckily, in the interim, Matthews’s longtime friend, LD Taylor, had been elected mayor, and was sympathetic to his cause. And, on June 15, 1931, following a lengthy campaign, Matthews was given an office in the drafty attic of the city’s library annex. There was only one catch: owing to the state of the city’s finances, the position was unpaid. Matthews had no formal training as an archivist or historian, and before this point, had only dabbled in the area. But for him, it represented a win—one he would spend the next 40 years building upon.

“It was an even more significant decision than [Council] realized at the time,” Sleigh writes in her book, “for once the Major’s foot was in the door, there would be no dislodging him. Any attempt to influence his style of management would be warded off with ease; any hint that he might retire would prove futile. However many battles would be fought over the next 40 years, Major Matthews would always emerge victorious, the protector of his beloved archives.”

The attic room Matthews had been given was drafty and poorly maintained: it had no heat, electricity, telephone, or typewriter, and it could only be identified by the handwritten sign tacked to the door. But, thanks to the boundless energy of Matthews, it quickly grew in scope to include hundreds of photos (some of which were commissioned by him personally), a painting of the first meeting of city council, and a history book that contained hours upon hours of interviews with city pioneers (later published as Early Vancouver, it remains an invaluable source for local historians).

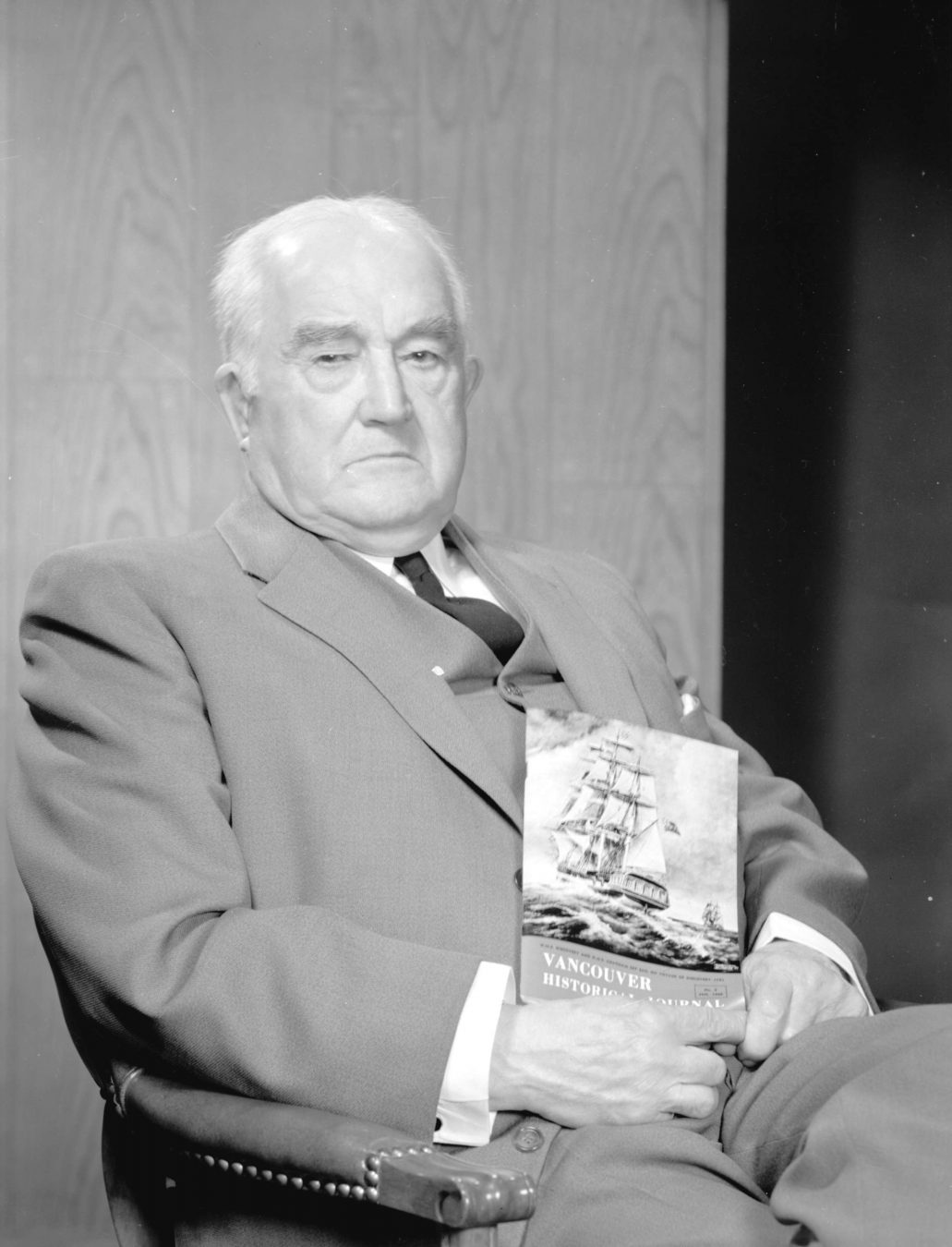

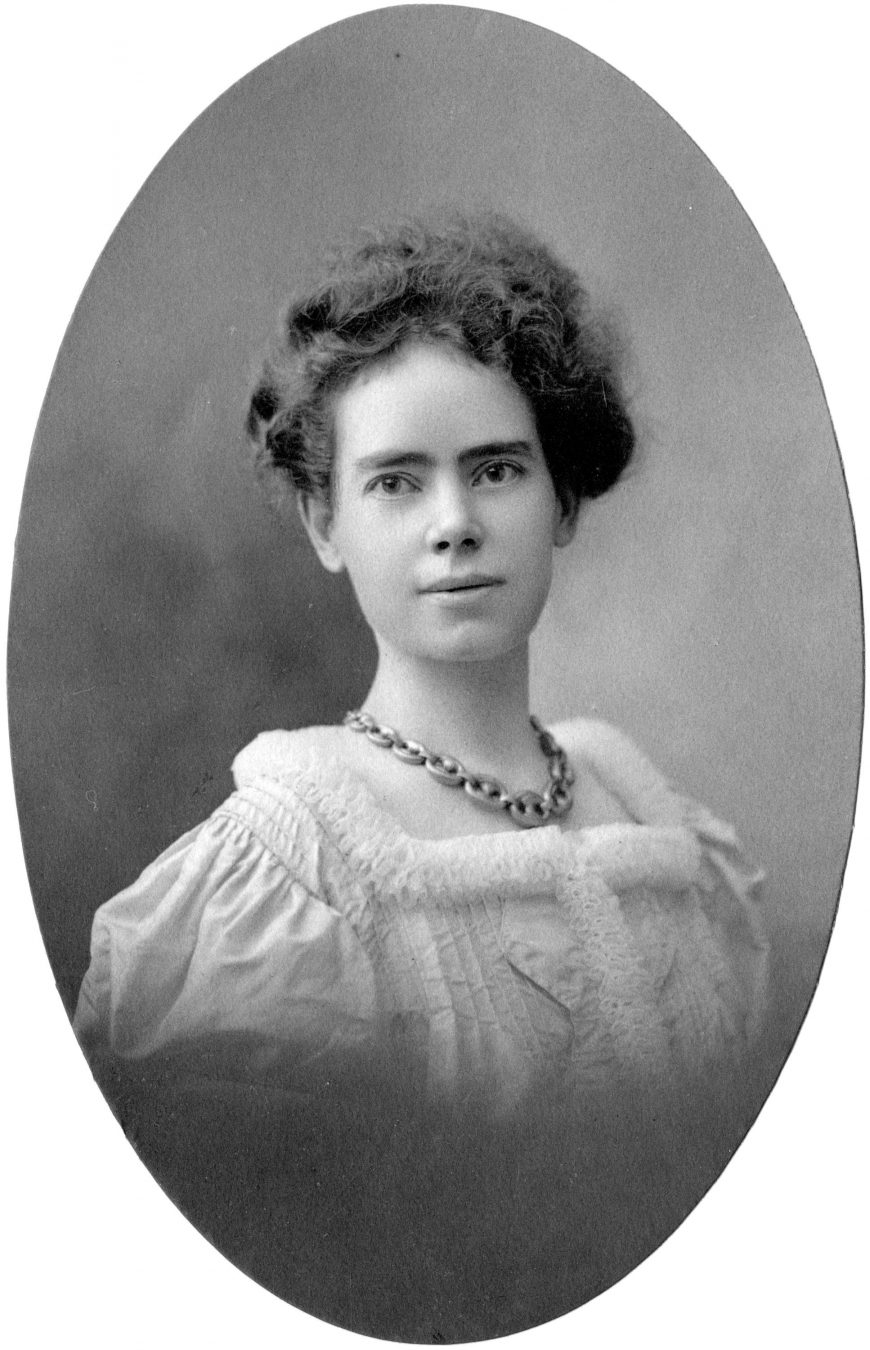

Emily Edwards, Matthews’s second wife, in a portrait taken shortly after they met, circa 1902. Image courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives.

For a year, Matthews begged, pleaded, and pressured council, until finally he was granted a monthly salary of $30, and an annual acquisitions budget of nearly $400. However, while his relationship with council had improved, his relationship with the Library Board (to whom he technically answered) began to deteriorate rapidly.

A dispute with chief librarian Edgar Robinson soon escalated to the point where Matthews had moved all archival material back to his basement. By November of 1932, Robinson was threatening termination. By early 1933, the city solicitor had become involved. Luckily, Matthews had a staunch defender in provincial archivist Hosie, and Hosie (along with other supporters, including timber baron William Malkin) managed to convince city council to create a separate archives department, with a budget, facilities, and Matthews at its head.

The archives would ultimately be housed on the 9th floor of city hall itself, but all the same, Matthews continued to grumble, bellow, and plead his way forward, demanding more material, a better salary, and a bigger budget. These things he received, although in 1938 he was convinced, against his better judgement, to gift the entirety of the collection to the city—a decision he would complain about for the rest of his life. During the years in city hall, he continued to do battle with successive mayors and aldermen, and was regularly gruff and impatient with the academic researchers who used the archives (he once physically removed a Swiss postgraduate student who had the gall to accidentally drop a folder).

But into the 1950s, his work began to be recognized citywide, and provincially; in 1953, he was awarded The Freedom of the City (the top civic honour), and in 1959, he was made Kitsilano Citizen of the Year. Despite successive councils’ attempts to unseat him, he never retired. He commissioned and raised the money for the statue of Lord Stanley that stands in the entryway to Stanley Park. He worked with city council to purchase the St. Roch schooner, now on display at the Vancouver Maritime Museum. During those years, he remained as irascible as ever (a staunch patriot, he once fell out of his chair with rage upon glimpsing Canada’s new maple leaf flag), continuing into his nineties to obtain a dedicated home for his collection.

Then, in 1968, he finally got a letter announcing that a permanent structure would be built in Vanier Park, as part of a centennial project that would also include the Vancouver Museum (now the Museum of Vancouver). Unfortunately, Matthews didn’t live to see its completion; he died a month after his 92nd birthday, by then completely deaf, and having never stopped working. Today, the facility at Vanier Park bears his name, and features a collection that contains 4,000 maps, more than one million photographs, 2,000 works of art, and extensive newspaper clippings dating back to the 1920s. It’s a place where, after more than 40 years of fighting, Vancouver was finally (and permanently) saved.

This story from our archives was originally published on February 15, 2019. Keep up with our Hidden Vancouver series.