Deas Island Park is a special place. Walking the perimeter path lined with tall grass, river views, and cool breezes silences the mind. It feels isolated despite being a part of Delta, and has an element of wildness in the craggy rocks and small footpaths that lead to the water. Poplar trees make the air sweet, and other than a lone Queen Anne-style house and a single rusted boiler, it is practically wild. Peace and quietude are found in abundance here.

But 145 years ago, the island was the site of the bustling cannery belonging to John Sullivan Deas: a British Columbia canning pioneer and one of the province’s first prominent businessmen of colour.

Deas was born in 1838 in South Carolina, in a small community of black people free from slavery. By the time he was a teenager, he was a trained tinsmith and was looking to leave the South, so he headed to California in 1860 but found the state hostile to the presence of African Americans. The Fugitive Slave Act had decreed at the time that former slaves found to have escaped could still be returned to their owners from free states like California, and frequently, claims on free black people could be upheld by the courts despite little to no evidence they had been enslaved. In addition, California did not allow black people to vote or participate in juries or civil processes. It was a temporary stop for Deas, who stayed with family and worked his trade, made some business contacts, and eventually found his way to Victoria on Vancouver Island in 1862. He later married Fanny Harris from Hamilton in what is now Ontario, and together they had eight children.

As he was beginning his family, Deas worked in Yale, operated a hardware store in downtown Victoria, and participated in community life. By the time the Gold Rush was beginning to die down, he came upon a different opportunity for making money: fish canning.

Shannon King, manager of audience engagement at the Gulf of Georgia Cannery Society, points out the tone of the times. “The 1870s to 1890s is sometimes referred to as the Salmon Rush because anyone with enough capital could start a venture and spring up a cannery,” she says via phone. In 1871, English ship captain Edward Stamp had his eye on fish canning. Efforts in the 1860s had not been successful, but Stamp was an entrepreneur—one of many convinced that the enormous stocks of fish in the Fraser and Columbia rivers could turn a profit with the right approach. Stamp hired Deas to make the cans for his venture in B.C. Their first season together went well, and Stamp left for England to raise more capital; while abroad, he died suddenly and unexpectedly of a heart attack.

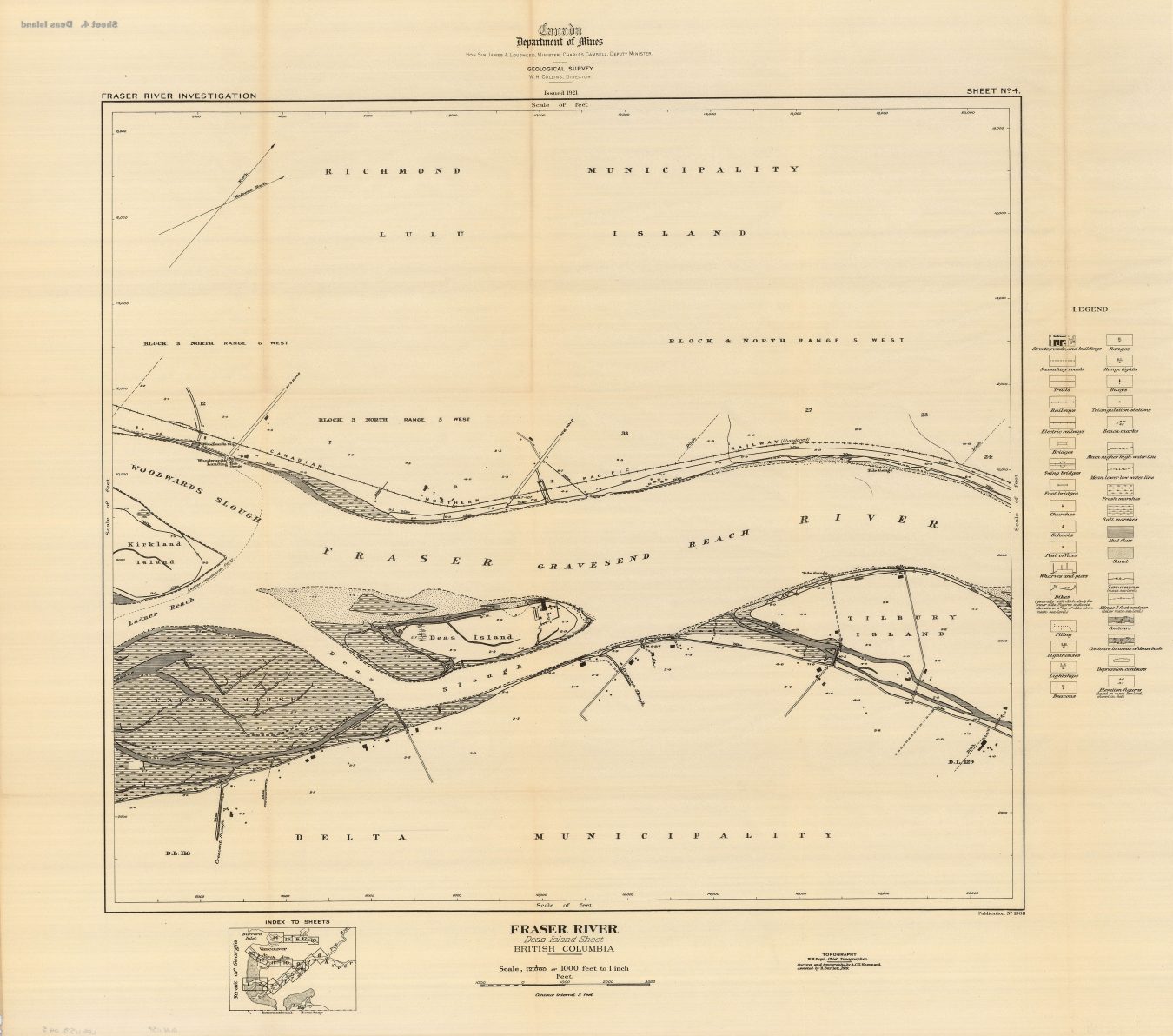

There were a trio of investors who acted as agents for Stamp, and they took over his business dealings after his death and continued the relationship with Deas. Operations were set up at Cooperville, land just opposite of what is now Deas Island. But the location was not without its problems: in particular, the shallow water of the shore made it hard for ships coming in to load cans. Then, in 1873, Deas realized that the deep water surrounding the island near their operation would eliminate those issues. Through the process of pre-emption, a term used to describe a settler’s rights to purchase public land by developing it, Deas acquired the island and quickly set up a large-scale project. Construction of a wharf, outbuildings, warehouses, and even living quarters were built over seven acres. Deas was now the face of the operation—he owned the land and the buildings, and his name appeared on the cans of salmon he exported.

He was one of the first in the industry, but certainly not the last; the next four years saw increasing encroaches on his land as well as heightened competition for profits and of course for the precious runs of salmon, which fluctuated wildly between seasons. Outnumbered and with dropping sales, and after exhausting legal battles over fish runs and land, Deas finally had enough, and in 1877 sold his business to the same trio of investors who had done dealings with Stamp. His family purchased a home in Portland and moved back to the United States.

In July 1880, Deas suddenly died at age 42; while the cause of his death remains unknown, it was speculated to be due to his former toxic occupation of tinsmithing. During his lifetime, he was remarkable for not only being a pioneer, but for emigrating from the slave-holding South and becoming a land and business owner, and a full citizen of his adopted country.

That boiler in the park is the only remnant of the bustling enterprise it must have once been part of, and is a reminder of the ambition and dreams of immigrants coming from around the world to B.C. Deas may not have ended up staying here, but his contributions to the province sure have.

Read more from Community.