This story is the 11th in our series on the hidden history of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. Read more.

In the 1970s, Vancouver city council set in motion a plan to develop the last untouched area of the city. The 614-acre expanse of forested terrain, which also included a landfill, was a blank slate to create a neighbourhood that welcomed various income levels near to amenities, transportation, shopping, and—um—a golf course. “It’s the most imaginative use of land.… It’s the first attempt to provide a balanced approach to the housing problem,” city planner Dan Graham told The Province in 1970.

The biggest challenge was coming up with a name. Sparsbrook and Fraser View were bandied about, but after two secret ballots, city council settled on a different name: Champlain Heights.

Spoiler alert: the problem of housing in Vancouver was not solved by Champlain Heights. It is natural, however, that this first attempt took place in Killarney, an east-side neighbourhood (bounded by Vivian and Earles Streets to the West, Boundary Road to the east, East 41st Avenue elbowing into Kingsway to the north, and the Fraser River to the south) that became the city’s final frontier. Without drawing much notice from the city’s history books or attention from folks elsewhere in town, Killarney has acted as a laboratory for Vancouver’s demographic challenges and a battleground for the city’s future.

Since time immemorial, most of the area that would become Killarney consisted of hemlock and cedar forest. The area’s largest salmon stream was Still Creek, which rose where Killarney Park is now found. One of its earliest European settlers was a British land surveyor turned saloonkeeper named William Rowling, who, in 1868, was given a riverfront land grant. Rowling travelled from his previous home in New Westminster on a barge along with his wife, five children, some furniture, and a goat. A decade later, in 1878, engineer George Wales purchased a parcel of land in the north end of present-day Killarney.

In 1891, the construction of the Central Park interurban line—equivalent in route to the SkyTrain’s Expo Line today—spurred development in the city’s bottom-right quadrant. Part of the District of South Vancouver from 1892 until 1929, when it was merged into Vancouver, the area remained largely bucolic farmland through the first half of the 20th century.

Although experts are now calling for Fraserview Golf Course (valued at over $700 million) to be converted into much-needed public housing, while others prefer it as park space, it originated as a Depression-era public works project. Before it opened as the city’s first public golf course in 1936, locals were invited to use the land for vegetable gardens and firewood. After the golf course was built, it became a respite for Second World War veterans who had moved into housing projects in the Victoria-Fraserview area. “Fraserview is where the Common Man comes to play golf,” Pete McMartin opined in a 2001 column in the Vancouver Sun. “[Its] wide, lush fairways are bordered by dense galleries of big, cloud-like trees.… You tee up, you look down the fairway, and there, before you, is another pastoral Eden stretching away between a chute of towering trees.”

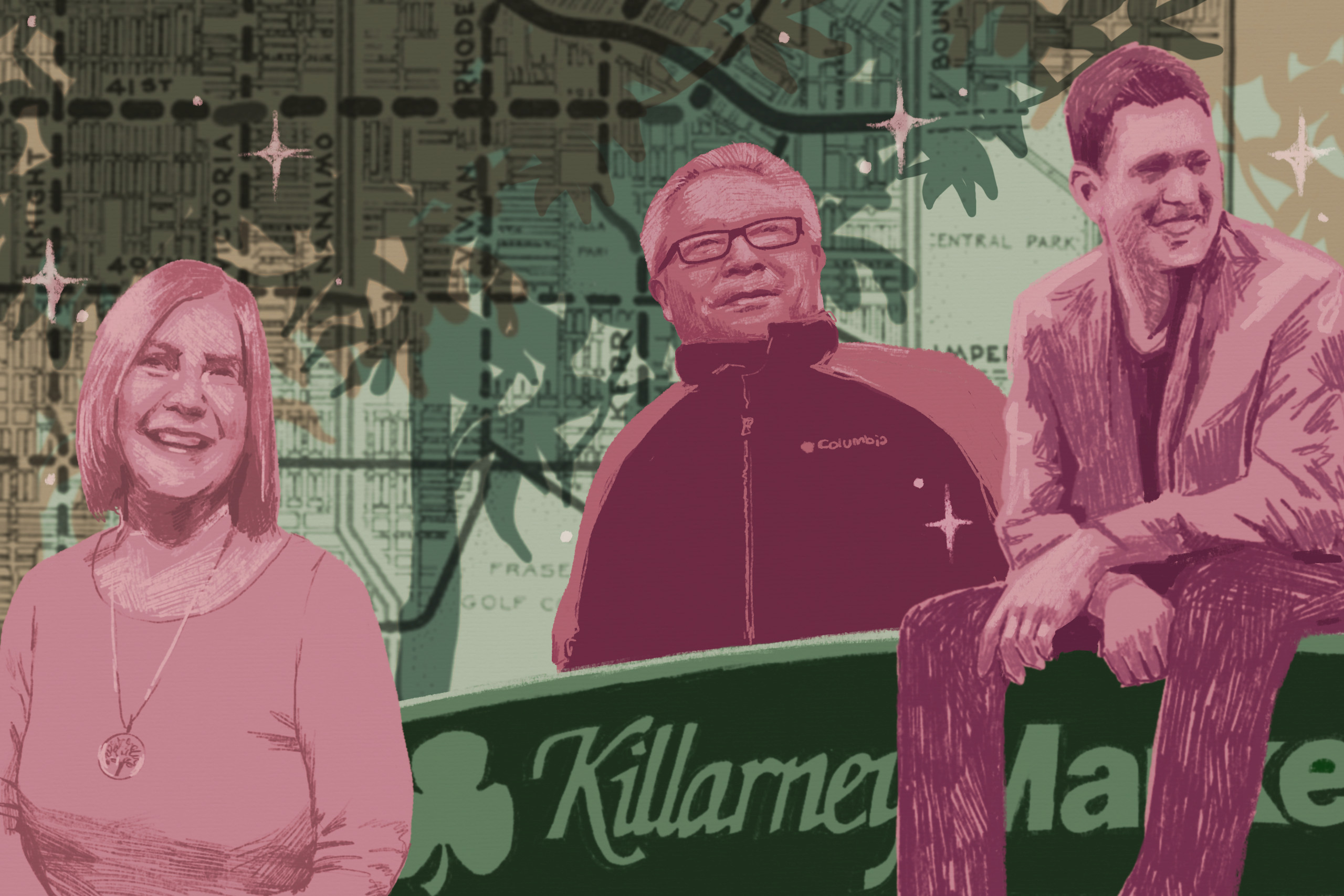

It was likely in the postwar period that the neighbourhood, its population swelling with Irish Canadians, acquired its name. In 1957, at the opening ceremony for Killarney Secondary School on newly drained bog land, a plaque embedded with a stone from the district of Killarney, Ireland, was placed in the school’s foyer. Later, in the 1990s, the heart of the neighbourhood was also fed by the Killarney Market. Tended by Tito Chiang, who has Chinese Peruvian roots, the market boasted food from over 40 countries and, in 2009, served as a setting for a Michael Bublé video. “There’s no ‘ethnic aisle’ here,” Christopher Cheung wrote in a 2018 appreciation commemorating Chiang’s retirement. “International goods are everywhere.”

When it was introduced in the early 1980s, Champlain Heights evoked the suburbs with its cul-de-sacs and winding streets, which were meant to slow traffic. Along with public and co-op housing for lower income residents, leasehold properties allowed homeowners a lower price point of entry. When it opened in 1987 bordering Champlain Heights, Everett Crowley Park encapsulated garbage 49 metres high that made up the old Kerr Road dump. The park celebrates its namesake, a parks commissioner who once served three days in jail in protest of the poll tax, a second time with Avalon Pond—named after his family’s long-running southeast Vancouver farm, Avalon Dairy. The area’s junk-streaked natural splendour is seen through a child’s eyes in Pam Galloway’s poem “El Dorado: Champlain Heights”:

“…inside these straggling tracts

of woodland behind the housing co-op

under the cans, the plastic milk jugs

and a rusted, sad-eyed rocking horse—

all kinds of treasure is buried,

when you’re young enough,

you want to spend each day

going tree to tree looking

for signs.”

Meanwhile, the part of Killarney attached to the city’s grid beckoned new homeowners who had recently emigrated from Asia in the 1980s and 1990s—and became one of the heated battlegrounds over “monster homes.” The relatively affordable area allowed for new construction of so-called max-sized homes, which irked longtime residents, who were also displeased that these residences often accommodated multiple families (or generations). One 1987 Vancouver Sun article by Carol Volkart quoted a resident who described his neighbour’s newly built home as “the monstrosity,” blocking the sunlight from the grapevine on his own property. “If the grapes don’t have sunshine when they blossom,” he complained, “they don’t bear.”

More recently, the Fraserlands of Killarney south of Marine Drive, an area previously devoted to lumber processing, has seen the development of the River District. Again, social housing was promised and packaged alongside more developer-friendly real estate holdings. In 2021, Maryse Zeidler of the CBC reported that revenue shortfalls have limited public transportation routes to the area and delayed long-promised amenities such as a community centre.

Half a century after the housing problem was first tackled, Killarney is still being touted as the frontier where imaginative solutions might be found.

Read more Vancouver Neighbourhood stories.