Before the age of social media, texting, and emails, there was one prime method of written communication—letter writing. Composed on delicate pieces of stationery, these thin handwritten treasures are now considered a thing of the past. But thanks to an exciting acquisition by the University of British Columbia Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections, this lost art is being rediscovered again.

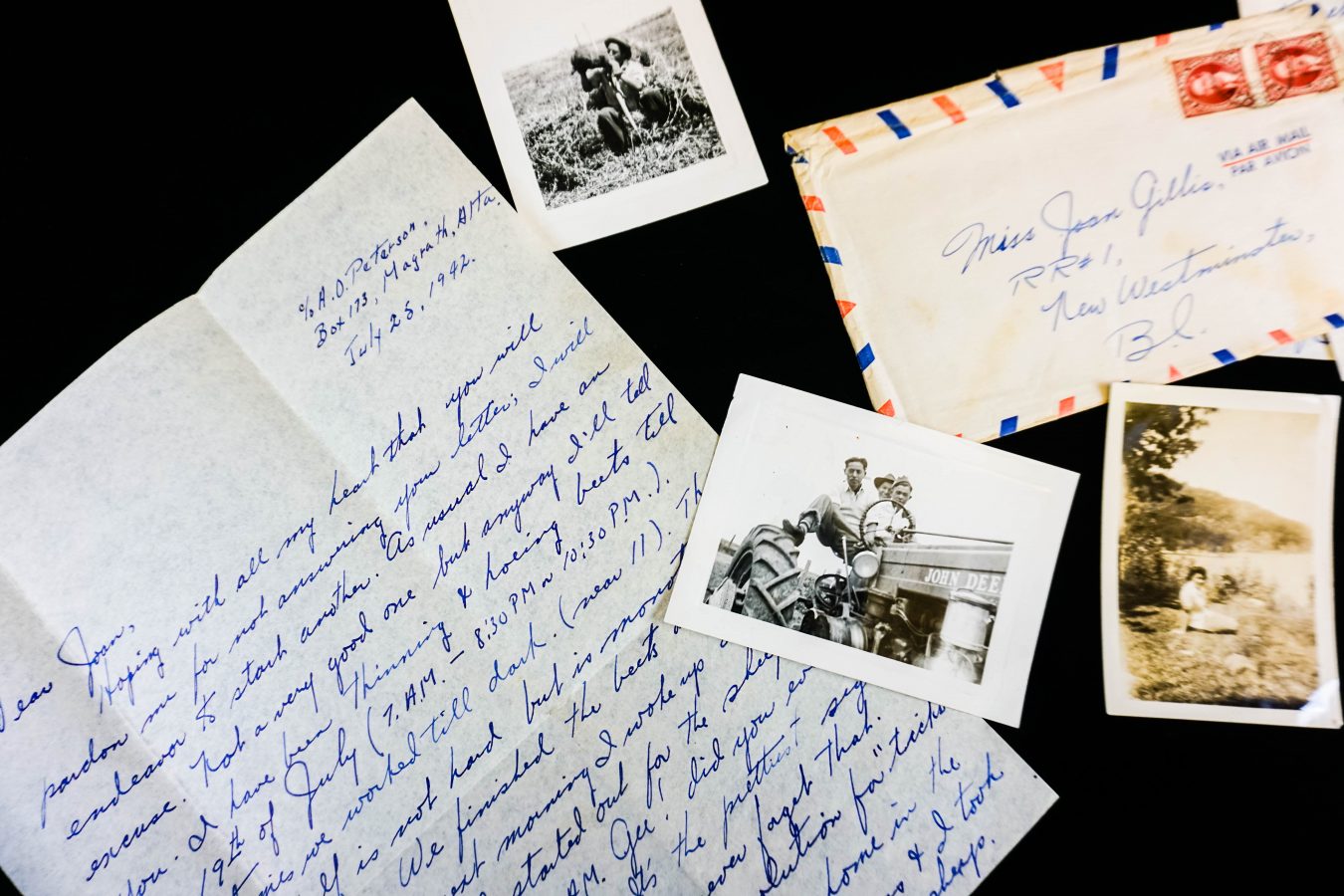

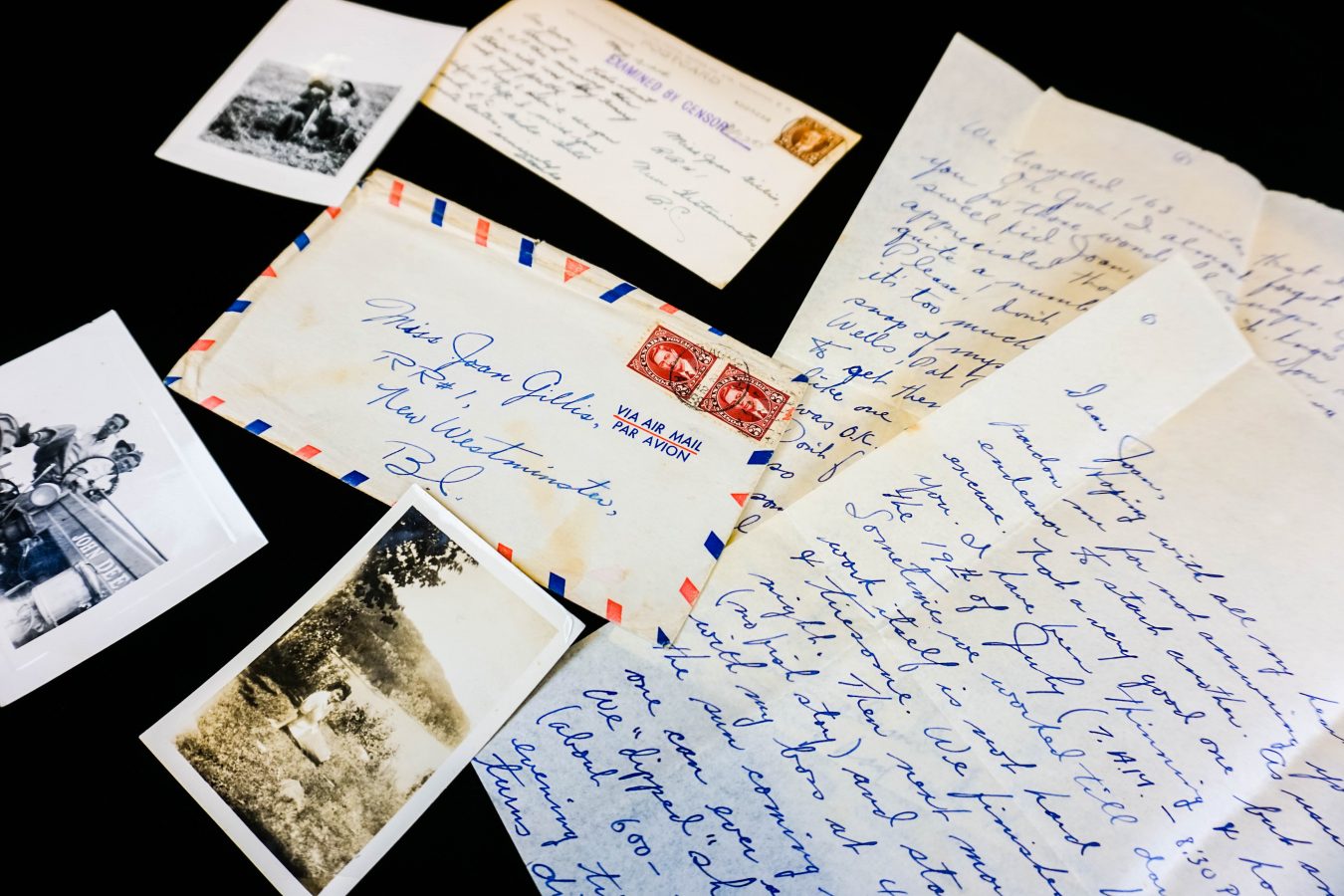

Written during the Japanese-Canadian internment period between 1942 and 1946, these letters provide insight into one of the darkest chapters of Canadian history. They are addressed to Joan Gillis, then a member of the newspaper club at Surrey’s Queen Elizabeth High School, who was 13 years old when she witnessed many of her classmates join the approximately 23,000 Japanese-Canadians banished from the West Coast following the attack on Pearl Harbour. Despite no evidence of a planned invasion with Japan, on February 24, 1942, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King ordered the forced relocation and segregation of this disenfranchised group. Most men were originally sent to work camps in the B.C. interior, with married men reunited with their families a few months later. The relatively few families allowed to remain together were sent to farming communities in Alberta, Manitoba, and Ontario. Over the next year, the Canadian government would also issue the liquidation of all Japanese-owned property to sustain the shantytowns where this population was left to reside. At the peak of such widespread racism and fear, Gillis began a correspondence with 13 of her Japanese-Canadian friends, as seen in the moving assortment of photos, birthday cards, and letters she received from them over 70 years ago.

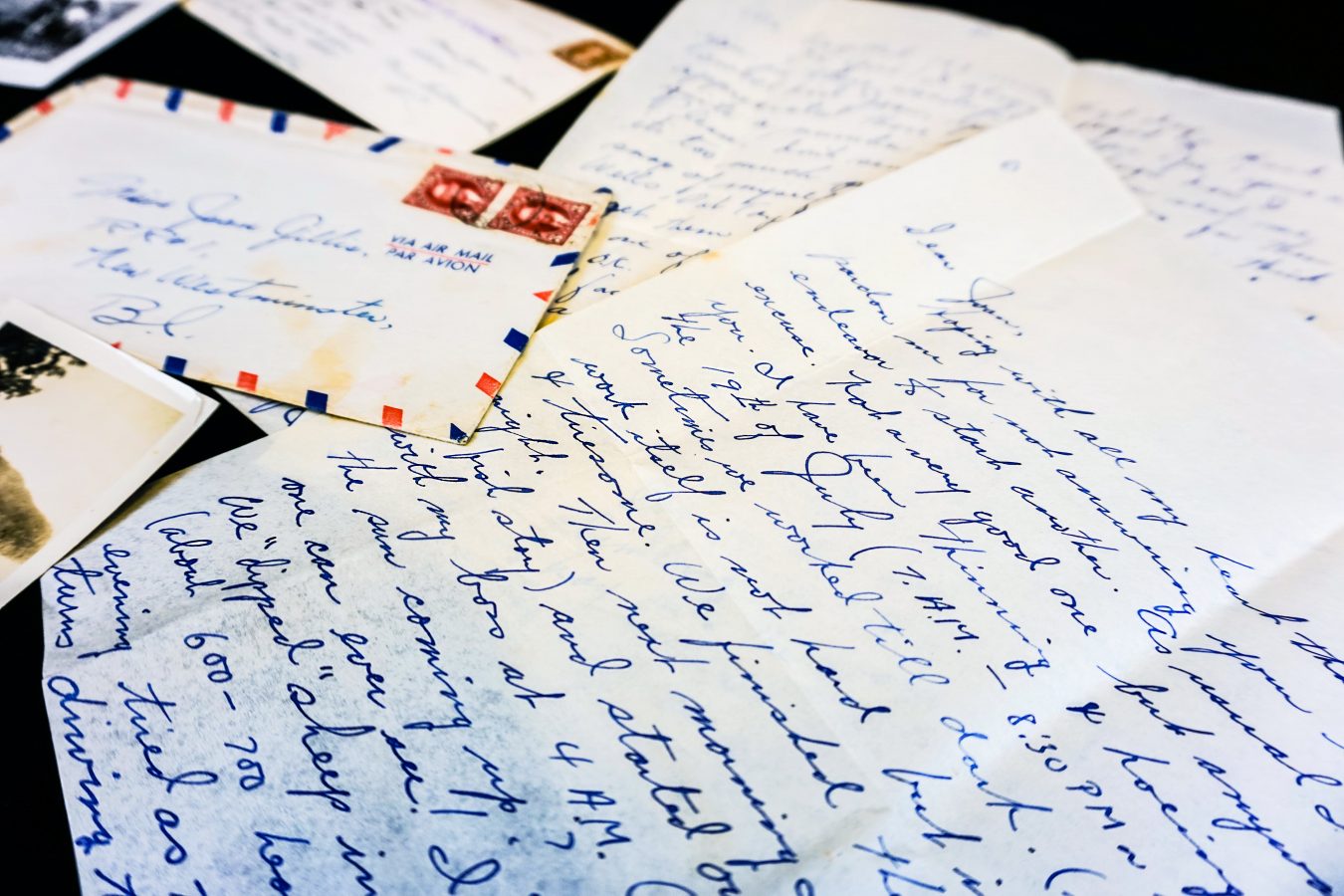

“I think some people make an assumption that those friendships didn’t happen and that people were very sort of ethnically and racially just stuck together,” says Krisztina Laszlo, archivist at UBC Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections. “We can show that people looked beyond those ethnic and racial stereotypes of the times and that they were friends.” Available for public viewing, the 147 collected letters offer an honest glimpse into the turbulent lives of these Japanese-Canadian teens. From working 12-hour days on sugar beet farms to wanting to know what the popular music was at the time, the letters portray how much these teenagers missed school, their friends, and life on the West Coast.

Inside a black case file, Lazlo reveals a sepia-tinted photograph of a young girl sitting down in a field, and another of three boys riding a tractor. Despite their situation, their expressions look cheerful. “It’s interesting when you look at the letters because the first few are so optimistic, and I think for some of the kids initially it was an adventure,” she says, looking over a letter written in perfect cursive.

Unbeknownst to them at the time, these first-generation Japanese-Canadians and their families would continue to struggle under strict regulations even after the end of the Second World War. Prohibited to return to the coast until 1949, most families began new lives by remaining in the Prairies or moving further east. For Gillis, this meant that she would never see her friends again, save for one who she reunited with later in life.

Now a 90-year-old retired schoolteacher, Gillis donated the letters and photos just in time to mark the 30th anniversary of the Canadian government’s Japanese-Canadian redress. In a formal apology, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney signed a $300 million compensation package on September 22, 1988, which included the distribution of $21,000 to each of the 13,000 survivors, as well as $24 million to establish the Canadian Race Relations Foundation (a charitable organization dedicated to the elimination of racism in Canadian society). Japanese-Canadians are one of the only groups to be disenfranchised in this way and receive monetary compensation after decades of campaigning—so the acknowledgement, and its anniversary, is of great significance.

A compelling source of research and education regarding one of the most tragic events in our nation’s past, these letters to Gillis have found a worthy home at UBC. They are bittersweet treasures waiting to be shared.

Read more about your Community.