Nestled amongst the trees on the eastern shore of Indian Arm are two gothic-looking buildings that have been weathered by more than a century of rain and damp.

Patrolled and off-limits to the public, they are little more than curiosities today, a favourite of urban explorers and film crews looking for somewhere appropriately creepy (most notably used as Pennywise’s lair in the 1990 miniseries It); but when they were first constructed at the dawn of the electric age, the Buntzen Lake Powerhouses were big news. Not only were they the first of their kind in North America to be created in a very specific way (more on that to come), but they were also at the centre of a major controversy—one that involved corporate skulduggery and corruption at the highest levels. It was an epic power struggle between the company who built them, the federal government, and the City of New Westminster.

“Prior to 1905, electricity in the Greater Vancouver area was run on steam power,” explains Will Koop, who has extensively researched the history of British Columbia’s watersheds. “This was the big transition. BCERC [the BC Electric Railway Company] set up this hydro plant. And then there was a bunch of intrigue around them and the other companies who were vying for control in the area.”

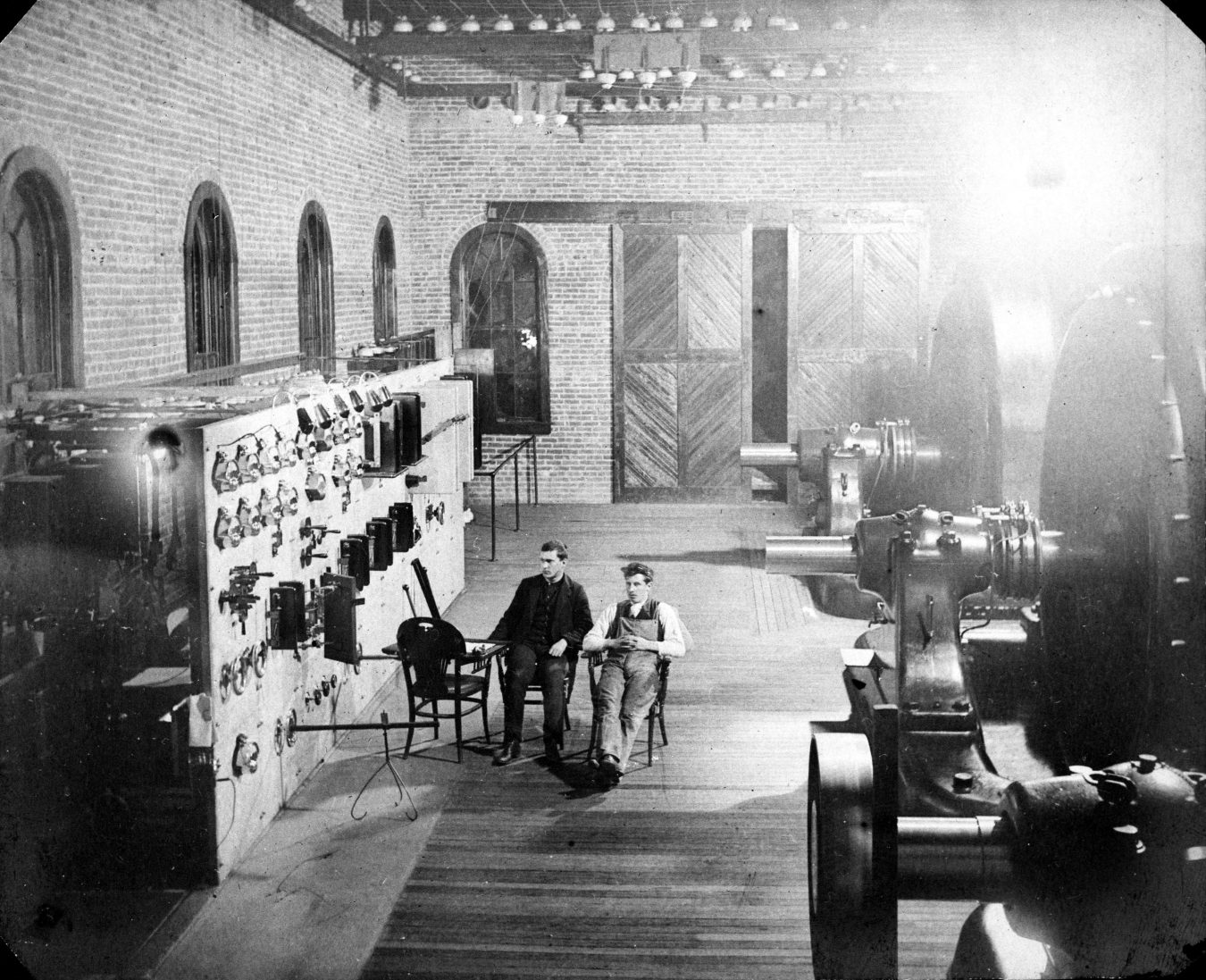

At the time of its completion in 1904, Powerhouse #1 was considered a technical marvel—not just because it electrified Vancouver, but because of the source of its power: what advertisements of the day called “white coal” (melted snow rushing through a 2.4-mile tunnel drilled between Coquitlam Lake and what was originally known as Lake Beautiful, later dubbed Buntzen Lake). Near the turn of the century, electricity was still a relatively new technology. Electric street lights had begun to appear in Vancouver as early as 1887, but they were less than inspiring; drawing power from a steam plant on Pender and Abbott, they required constant maintenance and were usually so dim that city archivist JS Matthews remarked in Early Vancouver, Volume Seven: “The joke at the time was that one needed a candle to find the electric light.”

But the advent of hydro-electric power changed all of that. Suddenly, the movement of mighty waterways could be harnessed to electrify entire cities, and in a place like Vancouver, surrounded as it is by lakes and mountains, that meant the potential for untold profits. “White coal is the greatest of all British Columbia’s great assets,” announced an ad in a September 1909 issue of the Financial Times that was uncovered by Koop, “the most plentiful of all its resources.”

Interior of Powerhouse #1, circa 1907. Photograph courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives.

It was back in 1897 that the BCERC—the predecessor of BC Hydro—was born. And while the company’s board and shareholders were based in London, the task of supervising North American operations was handed to a Danish-born immigrant named Johannes Buntzen. Later dubbed the granddad of electricity in British Columbia, Buntzen was seen as level-headed and forward-thinking, a man popular in the city and among his employees. Behind the scenes, it’s unclear how much control Buntzen actually had over the BCERC’s operations—all major decisions came from London—but in any event, he was a man unafraid to push the company’s agenda. It was under his watch that the site for Powerhouse #1 was selected in the fall of 1901, and an ambitious scheme was hatched to power it: diverting water from Coquitlam Lake into nearby Lake Beautiful via a tunnel drilled through 13,000 feet of solid granite.

“It was quite a feat, what they did, to go through 2.4 miles of solid granite from two separate ends,” Koop says via phone. “It had never been done anywhere in the world. And they met in the middle. Back in those days, the technology was kind of crude. They were reliant on instrumentation, but the engineers that drilled the tunnel on either side were only off three-quarters of an inch when they met.”

From Coquitlam Lake, the water would hit the dam and then travel an additional 400 feet to drive the turbines in Powerhouse #1 waiting below. But the BCERC had a problem: Coquitlam Lake was also the water supply for nearby cities like Coquitlam and New Westminster, and those municipalities weren’t eager to share. The Coquitlam Water Works Company, which was responsible for the reservoir, had thus far been successful in protecting its drinking water from other corporate interests, but it had reckoned without the seemingly endless supply of cash the BCERC (and its subsidiary, the Vancouver Power Company) had flowing in from London—and in 1902, the BCERC simply bought the Water Works charter. Anticipating local opposition, the company kept its initial proposal small in scale: a 19-foot dam that would, the team insisted, divert only a small amount of water from both lakes. Work on the tunnel commenced later that same year, and while it was a technical marvel, it was also a workers’ rights nightmare. Conditions were harsh, and there were frequent accidents and fatalities. “A lot of people died,” says Koop. “They were on three shifts, going 24 hours, and even when men died, they had to keep on working. They couldn’t grieve, because the bosses just kept cracking the whip. They were slave-drivers.”

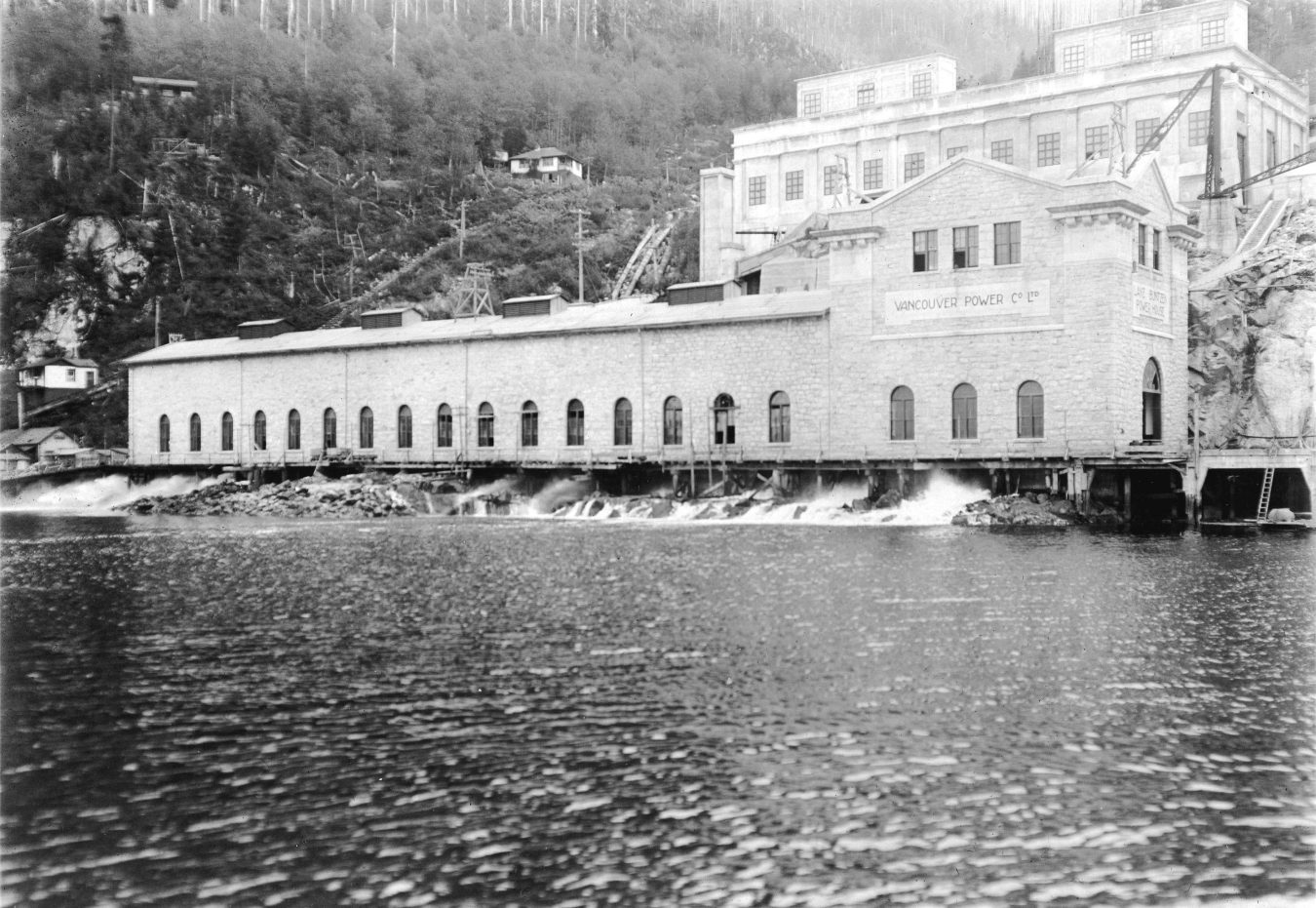

Powerhouse #1, shortly after completion in 1905. Photograph courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives.

The tunnel and powerhouse were completed in an astonishingly short period. In June of 1905, at a lavish ceremony attended by more than 200 people, the water was switched on for the first time, and Lake Beautiful was rechristened in Buntzen’s honour. Come December, the city of Vancouver was running on hydro-electric power; but the original dam—and the company’s promise of having a minimal impact on Coquitlam Lake’s water—didn’t last long.

By 1908, the dam was leaking so badly that as much water was being lost as was running through the tunnel. By 1909, there were thousands of dead, rotting salmon on its surface—so many that men with pitchforks were regularly sent in to clear them out. On top of that, the entire project was illegal under federal law, which stated that any water diverted from one watershed had to be returned to its original source. But rather than step back from a challenge, the BCERC ratcheted up its plans. Demand for electricity in Metro Vancouver was increasing faster than anyone had expected; two years after construction on Powerhouse #1 was completed, the company was forced to install additional generators—something they continued to do at a rate of almost one per year until 1912. In order to keep up, they argued, they would have to build a second powerhouse, and raise the dam to a whopping 98 feet, thus tripling the water flow from Buntzen Lake.

When they caught wind of the proposal, Coquitlam City Council members were horrified. Not only were they worried about what might happen if the dam burst, but they knew that such a move would decimate their water supply. They sent a petition to Victoria protesting the idea, and shortly after, other political entities joined the fray. In 1909, the Justice Department argued that such a move would destroy local fisheries, and New Westminster City Council sent its own engineering consultant to investigate. But the BCERC wasn’t backing down, instead buying off local newspapers to keep dissent out of the press and bribing politicians (Interior Minister Frank Oliver was so completely in the BCERC’s pocket that he provided the company with confidential government documents during a Supreme Court challenge launched by the City of New Westminster); even a former MP named Andrew Thompson was hired to take the company’s interests directly to the federal government.

Thompson was startlingly successful. Not only did he get the government to pull the water licenses of both New Westminster and Coquitlam (thus granting the BCERC virtually all of the water in Coquitlam and Buntzen lakes), but he also convinced politicians to change the legislation that required water to be returned to its source, thus fully legalizing the dam project.

By the time the new dam was completed in 1914, Johannes Buntzen was out of the picture. Whether he retired or simply moved on is unclear, but the lake that bore his name continued to serve the Greater Vancouver region, thanks in part to the construction of Powerhouse #2, which was finished that same year. Among historians, there is some disagreement over who actually designed the iconic structure—some attribute it to Francis Rattenbury, the architect behind the B.C. Legislature and Victoria’s Empress Hotel (who, in a sensational twist, was later murdered by his wife’s 18-year-old lover), but a more likely explanation is that it was the work of Robert Lyon, a lesser-known architect in the employ of the BCERC.

Powerhouse #2, July 2017. Photograph courtesy of Eve Lazarus.

Originally, the two powerhouses were operated manually by a small community of workers who lived in the hills above Indian Arm. Until 1953, when the facilities were finally automated, families inhabited the remote wilderness, sending their children to school in a building attached to Powerhouse #1 and receiving weekly deliveries of groceries by boat.

Today, the operation only supplies around 0.4 per cent of Greater Vancouver’s electricity. Powerhouse #2 was shut down in the 1950s; Powerhouse #1, which still retains some of its original hardware, remains B.C.’s oldest functioning hydroelectric power plant. The BCERC and Vancouver Power Company have long since been absorbed by BC Hydro, and their archives (some 200-plus boxes of correspondence) are housed at the University of British Columbia. But for those kayakers and urban explorers who are able to catch a glimpse of the lonely structures, they are a reminder of the white coal that the BCERC so coveted, and the lengths to which it went to get it.

This article from our archives was originally published on October 9, 2018. Read more from our Hidden Vancouver series.