In 2009, my sister Melissa Paget, a Vancouver-based visual and sound artist, was handed a mysterious briefcase. Found by a friend of a friend while dumpster diving in East Vancouver, the attaché case had a worn black-pleather exterior and a yellowed lining that smelled like an ashtray. Inside was tucked a collection of photos and ephemera belonging to a man named Chad who appears to have worked as an exotic dancer throughout the Lower Mainland in the 1980s.

The photos—a mix of snapshots and promotional materials—show Chad and his scantily clad friends performing, partying, and smoking cigarettes in brightly coloured leotards, legwarmers, and sky-high perms. A handful of personal notes, newspaper clippings, and doctor appointment reminders point toward a life lived in the fast lane.

The briefcase and its contents had passed from friend to friend. No one in the tight-knit community of artists wanted to get rid of the collection, but no one knew what to do with it either.

But when the case fell into the hands of my sister, who was developing an artistic collection of collages, drawings, and soundscapes at Emily Carr, she decided to turn the contents into a hand-bound, limited-edition art book. When I returned home that Christmas, I received a copy of The Book of Chad (number two in an edition of 10), which has remained on my bookshelf ever since.

Bound in a silver, holographic disco-ball cover set against a black background, the book contains photos and mementos arranged to create a narrative of sorts, an intimate look at a brief period in a stranger’s life, asking more questions than it answers.

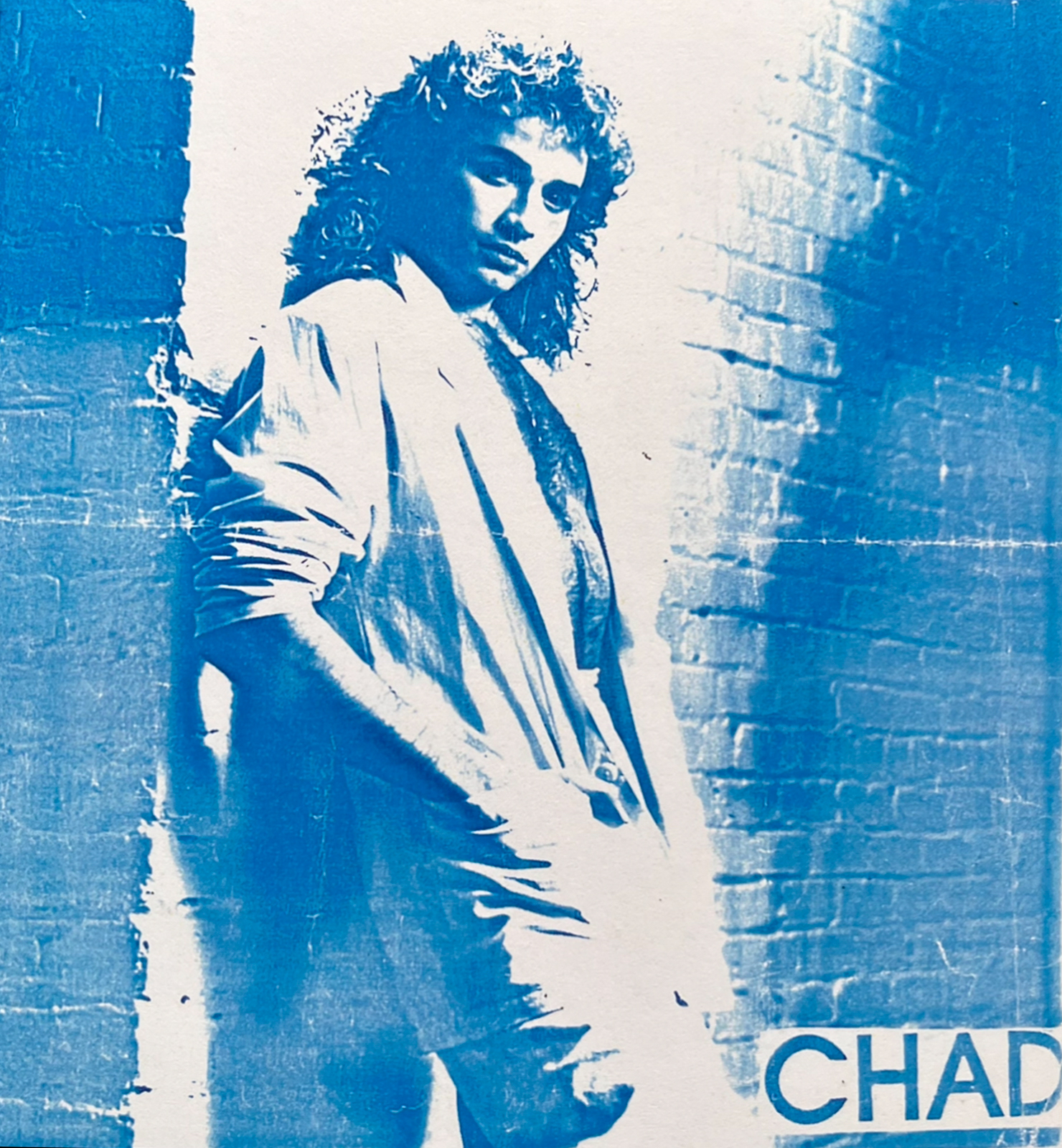

The book opens with a promotional photo taken in the late 1970s or early 1980s. Dressed in a white tuxedo with a ruffled shirt and black bow tie, Chad poses playfully for the camera, revealing his thigh and the waistband of his thong beneath white tearaway pants. Above the portrait, his stage name, “CHAD,” is printed in bold with the phrase, “YOU’LL BE GLAD” across the bottom. A line below notes he’s represented by Choice Entertainment (1500 Alberni Street), a talent agency I’ve been unable to track down. He appears to be in his early twenties, with dark brown hair, brown eyes, pronounced eyebrows, and a slight but athletic frame.

The Book of Chad is an intimate look into an exotic dancer’s life in 80s Vancouver. But it asks more questions than it answers.

The photos follow Chad’s evolution through hairstyles from a blow-dried David Cassidy mullet to an over-the-top perm with bangs straight out of central casting for a White Snake video.

The collection then jumps forward in time, ending with a prescription for Tylenol-Codeine No. 3. While there’s no issue date attached, the expiration date is 2009, suggesting it was written sometime in the mid to late 2000s.

The photos suggest a loose timeline about what may have happened in Chad’s life in the years in between.

Chad was the stage name of Glenn, a young man who worked as an exotic dancer for a period in the ’80s and possibly the early 1990s. He was a fan of rock music and saved a 1982 copy of the Georgia Straight with the Who’s Pete Townshend on the front page. He liked live music and had several photos from rock shows—one of an undisclosed band that looks as if it may have been taken in the early 1990s at Richard’s on Richards. Dressed like Axl Rose in a baggy white shirt, red shorts, and black Doc Martens boots, the lead singer’s expression is defiant as he gives two middle fingers to the photographer.

Chad’s female friends wander through the photo collection, including in promotional materials for fellow exotic dancers. A twentysomething woman with a sky-high blond perm lounges on the bed of a seedy motel. Wearing skin-tight cow-print pants, she smiles at the camera while casually smoking a cigarette.

In another photo, a woman with dark brown hair seductively peels away a zebra-print unitard. In the next, Chad dances in front of a band all wearing identical zebra-patterned leggings. It’s impossible to know the relationships between the women and Chad, but I’m curious about their stories. Were they lovers, friends, or simply coworkers?

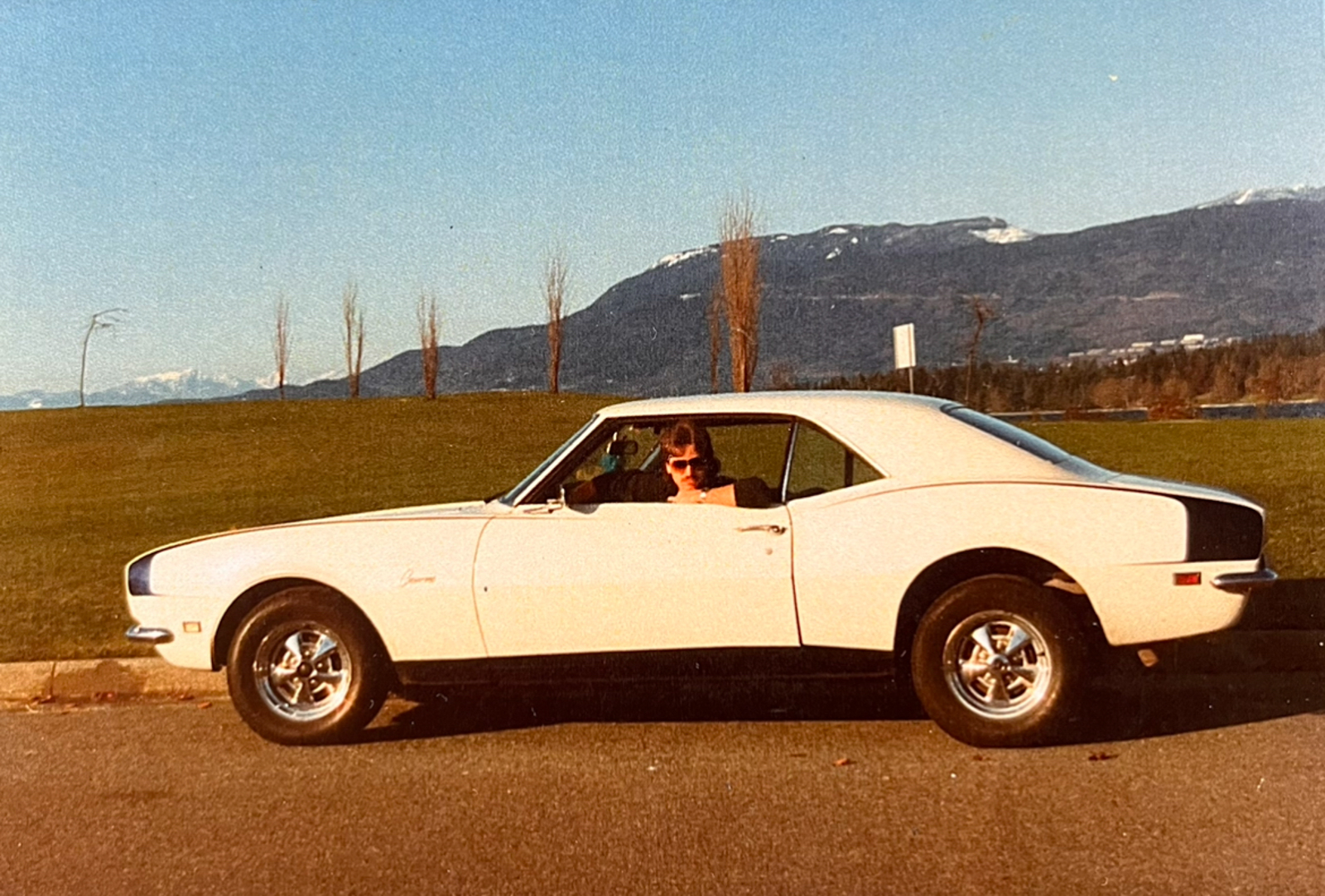

Mixed in with rock and roll decadence are photos of quieter, familiar Vancouver moments. Chad poses against a car, the snow-capped mountains of the North Shore rising in the distance. Chad embraces a female friend while enjoying a sun-soaked day at English Bay, a tipped-over Orange Julius cup and container of Kentucky Fried Chicken near the edge of the frame. Chad’s Expo ’86 season pass reveals his legal name on the back. In his photo he looks young and optimistic. His curly hair is now past his shoulders, taking up most of the frame.

Amidst the windows into his exotic dancer life, slices of normalcy also appear.

Midway through the book there’s a photo of Chad standing next to a woman. He’s wearing mirrored aviator glasses and sporting a curly mullet. They are clutching a baby, the woman smiling widely at the camera while Chad’s expression is blank and unreadable. On the following page is a love letter and a photo of a woman looking off in the distance. Written in 1984, it says:

“Dearest Glen, I would like to thank you for the way you make me feel. You have brought out a part and feeling in me that I didn’t know was there. I love you for that. I hope the future will allow me to share this with you more. With love, Sandi”

Did Chad have a child? Was Sandi the mother? Or was she “the one that got away”? What, really, can we know about someone from a collection of photos and pieces of paper?

It’s these moments of tenderness that I find the most compelling and haunting. Because of the ambiguity, but also because they subvert a stereotyped image of sex workers’ lives—an image that doesn’t include trips to Expo and days on the beach.

Over the years, I’ve returned to The Book of Chad in search of clues I might have missed. Sometimes I notice a new detail—a reflection in a pair of sunglasses I hadn’t picked up on before. More often I’m simply left wondering: who was Chad, or Glenn, and why do I feel so compelled to find out?

Everyone who interacts with the collection feels a similar pull. Living in a world where nearly any question can be answered with the tap of a screen, it’s hard not to be seduced by a mystery that can’t easily be solved.

Plus there’s the ’80s kitsch factor. Chad’s photos are an archive of Vancouver nightlife history. They harken back to when Richard’s on Richards, Luv-a-Fair, and the Town Pump were the go-to spots for the hottest rock, alternative, and new wave bands, as documented in Aaron Chapman’s book Vancouver After Dark: The Wild History of a City’s Nightlife.

Ultimately though, I think our attachment to Chad’s ephemera comes from a place of self-preservation. We don’t want to imagine our own personal effects being unceremoniously tossed in a dumpster. By preserving Chad, we almost feel as if we’re safeguarding our own memories.

Over the past few weeks, I’ve done everything short of creating my very own war room, complete with thumbtacks connected by red strings, to try to learn more about Chad’s life. I’ve searched public court records, Googled ad nauseum, and even sent his photo to my friend Brent, who lived and partied in Vancouver around the same time, on the off chance he might recognize him. While I didn’t learn anything new, I heard about partying at the Odyssey, Vancouver’s iconic (and now-defunct) LGBTQ+ club, which regularly featured male exotic dancers in the 1980s. Brent suspects Chad may have performed there but can’t be sure.

An unknown woman in a neon swimsuit basks in the sun—friend, lover or coworker of Chad?

Over coffee last Saturday, my sister told me the briefcase originally contained several more photos, along with a collection of Narcotics Anonymous materials, scattered piecemeal amongst friends as it changed ownership. Someone had once been in possession of Chad’s Narcotics Anonymous sobriety keychain.

How many months or years did Chad have sober? What does this mean about where he ended up in life? Did he dispose of the briefcase, or did someone else (perhaps an ex or a landlord)? Is any of this even my business?

I’ve even considered reaching out to my cousin, a private investigator, to dig deeper into Chad’s whereabouts, but always abandon the idea. Although I have multiple photos of Chad in a G-string, investigating him somehow feels like a violation of his privacy. If Chad is out there, he may not want to be found.

In the meantime, I’ve made peace with never solving this mystery. That would mean the end of the story, which I’m not ready for. Instead, I prefer to appreciate the photos for what they are—vivid snapshots of a life with infinite possibilities.

Read more Community stories.