This story is the 16th in our series on the hidden history of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. Read more.

One of the youngest neighbourhoods on Vancouver’s west side, Oakridge emerged only in the second half of the 20th century. Perhaps for this reason, the area bounded by West 41st and 57th Avenues to the north and south, and Granville and Main Streets to the west and east, is closely affiliated with the signature urban development of that era: the indoor shopping mall.

The original Oakridge Centre, a shopping centre opened in 1959, is currently levelling up into Oakridge Park: a massive shopping and residential development with 850,000 square feet of retail space, along with four residential towers, a new community centre, and a library, all slated to open later this year. That means the area’s connection to climate-controlled commerce and food courts is ensured for another generation. Beyond the mall, though, Oakridge has grown consistently into one of the city’s most desirable residential areas and an aspirational landing spot for some of the city’s ethnic populations. Over the course of its history, it’s gone (via mass transit on Cambie and 41st) from the middle of nowhere to one of the more central and accessible areas of the city.

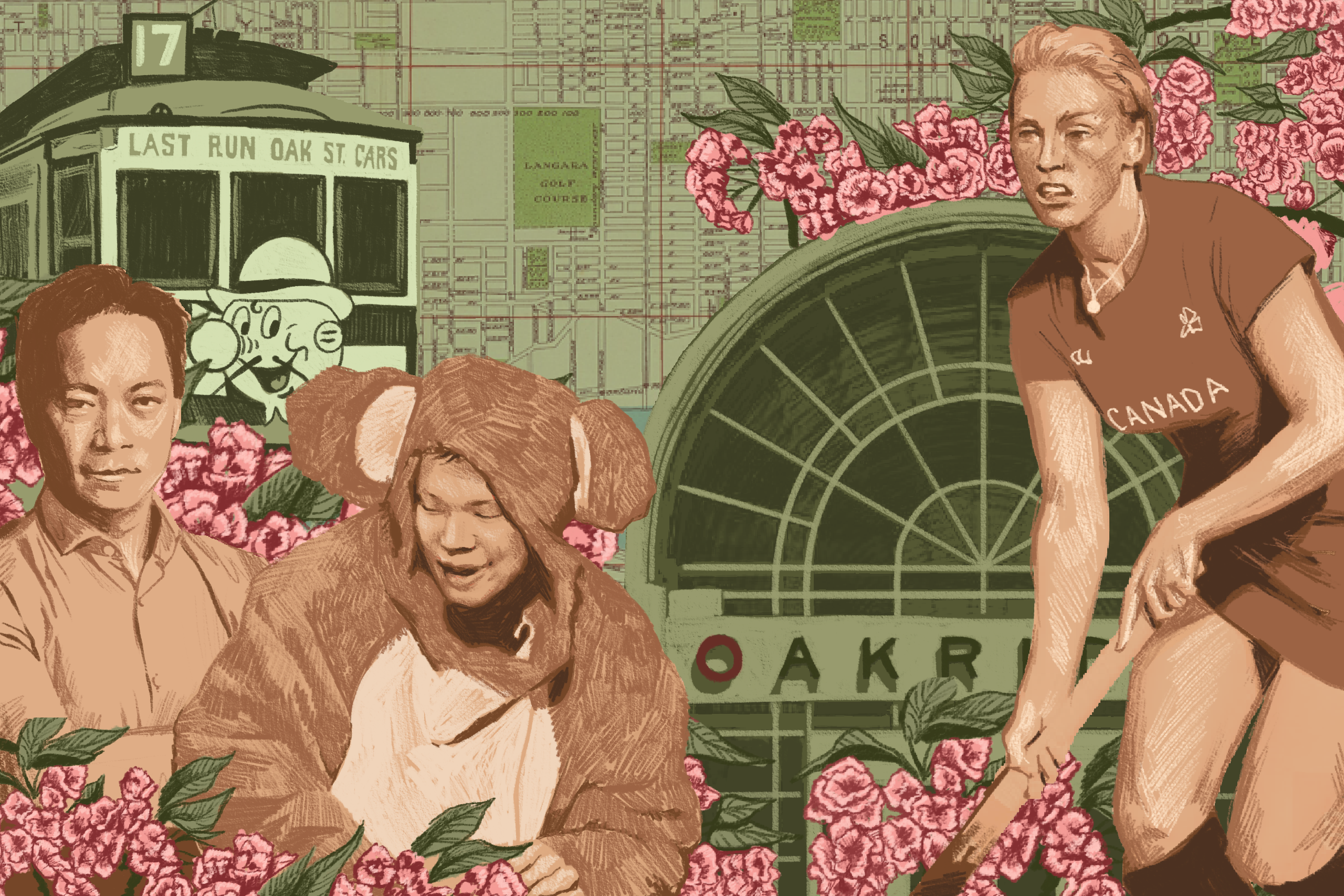

Oakridge took its first steps in 1950, when the Canadian Pacific Railway opened the undeveloped, forested land for commercial development. Before that, the area was primarily known for the Langara Golf Course. Built in 1926, it was the first public 18-hole golf course in the city. Other landmarks included the long-running Vancouver Gun Club on Oak Street and West 44th Avenue and an army barracks site that, in 1948, was transformed into the home base for the city’s streetcars, the Oakridge Transit Centre—the area’s first connection to its current name. The 14-acre site later became the home of BC Electric’s fleet of electric buses, which replaced the streetcars.

A photograph from 1952 shows gun club members, rifles held aloft, celebrating the Oak Street tram’s last trip. TransLink moved its buses from the Transit Centre in 2006, and the site, which sold for $440 million in 2016, is currently being developed into a residential highrise community. Last October, city council agreed to extend the deadline for the property developer to deliver on its promised 175 units of social housing from 2028 to 2033.

In the early 1950s, with the city in the middle of a postwar population spike, bungalows began to line new treeless streets. In 1956, the neighbourhood’s high school, Sir Winston Churchill Secondary, was built at Heather and West 54th Avenue. Famous alumni include the current mayor Ken Sim, former mayor and B.C. premier Mike Harcourt, field hockey player Tyla Flexman, and musician Kid Koala.

One of the first groups to relocate en masse to the area was the city’s Jewish population, which had originally been associated with the West End and Strathcona at the turn of the 20th century. “When we first moved to Vancouver in 1947, my parents went out with a real estate man to look at a house at 25th between Oak and Granville,” Irene Dobek recalls in an online exhibit about Oakridge for the Jewish Museum & Archives of BC, “and the real estate agent told my father, ‘This is a good neighbourhood, because no Jews or Chinese are allowed.’” Oakridge, by contrast, was more welcoming.

The outdated Jewish Community Centre, which had been located in Fairview Slopes, was moved to a larger site in 1962, at 41st and Oak. That intersection became the epicentre of Jewish life in the city, with Kaplan’s Delicatessen, the Louis Brier Home for the Aged, and Harry Caine and Jerry Morris’s Oakridge Drugs all located within a block of each other in the developing neighbourhood.

The centrally planned heart of the neighbourhood, Oakridge Centre, had been introduced in 1959 on a 29-acre property, with Woodward’s as its anchor tenant (succeeded by The Bay in 1993). The project cost $25 million, and the original site included outdoor parking, a state-of-the-art air conditioning system that used well water, and 2,600 parking spots.

A longstanding hub for high-school students, Vancouver’s first mall grew to incorporate medical offices and a library in the mid-1980s, when the open-air walkways were covered, and office space and community amenities were added. Local journalist Christopher Cheung, who grew up in Oakridge at the turn of the 21st century, wrote: “I knew it intimately as a kid, visiting the family doctor for my first colds and flus, meeting Santa at Christmas, fishing coins out of fountains, rolling in the carpeted play pit and lining up at the cinema for blockbusters like the Harry Potter series. Sprinkled among the stuff of typical malls like mmmuffins, the Bay and Electronics Boutique were more local offerings, like the underground library where I learned to read.”

Over the years, the mall has served as a location for TV shows like 21 Jump Street and Dead Like Me. It’s also been, on occasion, a crime scene. In December 1989, a Brink’s security guard was shot in the throat and left bleeding by two armed robbers, who ran off with half a million dollars. And one afternoon in October 2008, its underground parking lot was the scene of a gang-related murder.

Another amenity later built in Oakridge is Langara College, an offshoot of Vancouver City College that arrived at its West 49th Avenue location in 1970. Its theatre school Studio 58 features such notable alumni as writer-actors Carmen Aguirre and Sonja Bennett. Nearby, the YMCA, built in 1978, has recently submitted plans for a new site that includes a rental housing tower owned by the Musqueam First Nation.

In the last few decades, as Oakridge has secured its place as a preferred residential area, the modest homes that originally marked the neighbourhood have been torn down and upgraded with more luxurious digs. Part of the increasing affluence of the area has been attributed to what sociologist David Ley described as the 200,000 “millionaire migrants” from Asia who came to Metro Vancouver through business-investor immigration programs and largely earn (and potentially fail to report) their income overseas.

Writing about this phenomenon for the Vancouver Sun in 2015, Douglas Todd noted that the “neighbourhood south of Oakridge Shopping Centre also has a curiously high proportion of residents reporting poverty, even though most people there own either expensive houses or stylish condominiums.” Whether or not this conjecture is true, demographic information does show higher poverty rates in this expensive family-oriented neighbourhood, as well as a large ethnic Chinese population.

As Oakridge continues with highrise development, its fast-increasing density will change its population—and push its history as a site of scrub and rifle-slinging target practice even further into the past.