Emmie May Binns was married aboard a rum-running ship and spent her honeymoon smuggling Canadian liquor down the west coast of the United States—and that was far from the only adventure during her life on the Pacific coast. Her travels took her near Tofino to prospect for gold, to a fish cannery on a remote coastal inlet, into the waters of the Salish Sea to rescue a downed seaplane pilot, and to Vancouver to work as a telephone operator at the British Columbia Telephone exchange. Her seafaring prowess and love of adventure led to a life steeped in fascinating West Coast history.

Emmie May was born in 1909 in New York to an Irish father and English mother. In 1914, her family moved to Ucluelet, where her father started a trading post and was known as Captain Binns after being given a pilot’s licence for expertly navigating boats through the Alberni Canal (now known as the Alberni Inlet). Her mother died when Emmie May was 12, leaving behind Emmie May and an older sister named Phyllis. In 1928, after attending Girls’ Central School in Victoria, Emmie May moved to Vancouver with Phyllis, where they both worked as telephone operators.

At a party, Emmie May met Stuart Stone, who was captain of a rum-running ship called the Malahat. They hit it off straight away, but she refused to become involved romantically because he was married with children. Their paths crossed again a year later when she was bunking with her friend Hazel, a fellow telephone operator who happened to be Stuart’s sister. (Hazel apparently put through coded messages sent over short-wave radio to coordinate rum runs and alerted rum-running ships of the coast guard’s whereabouts, but that’s another story.)

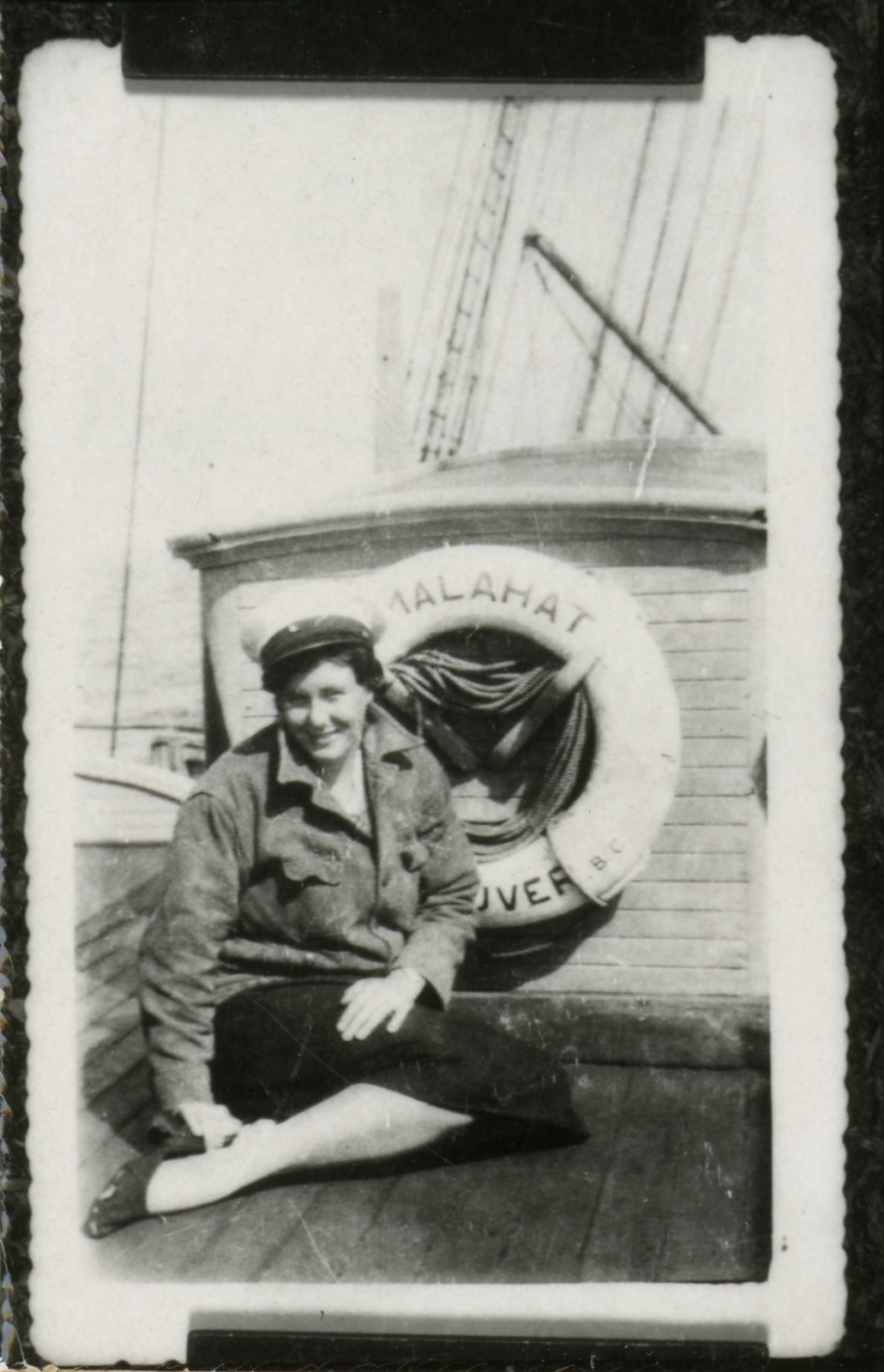

After Stuart’s divorce was finalized, Emmie May and Stuart were married. The ceremony took place aboard the Malahat on November 27, 1931. Though she was 22 and he was 42, they shared a love of maritime life and grand adventures. She joined him aboard his ship, spending the weeks after their wedding learning the ins and outs of rum-running. Staying home wasn’t an option: she loved exploration, her new husband, and the ocean too much to miss out on life at sea. As captain of the ship, Stuart earned a lucrative salary, along with thousands of dollars in secret bonuses, plus room and board.

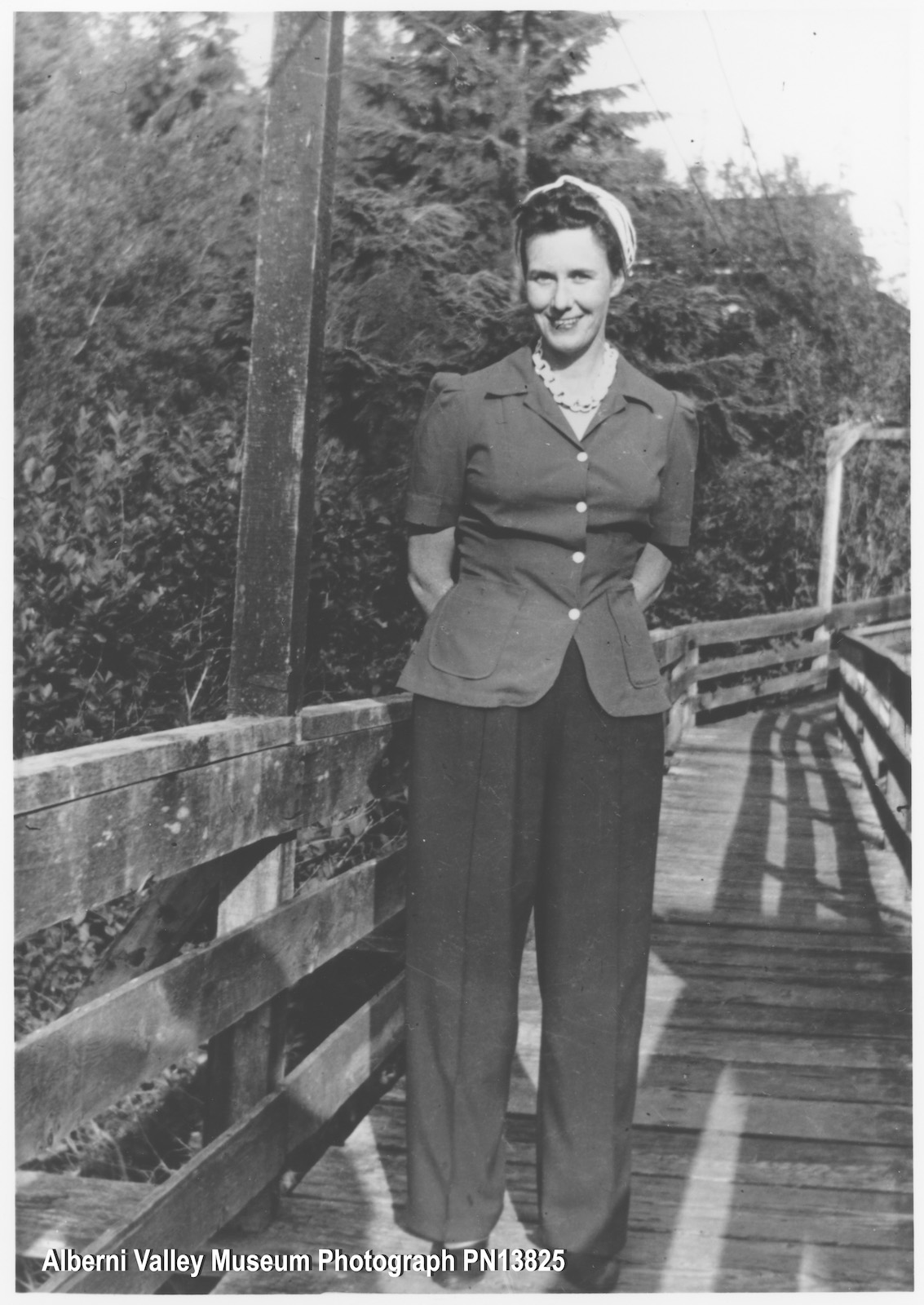

Emmie May in 1941, during her time working as a forewoman at the Kildonan Cannery. Photo PN13825 courtesy of the Alberni Valley Museum.

At first, the Malahat’s crew resented their captain’s new wife, now their fellow crew member, and one only spoke to her through others for six months. But the crew didn’t know Emmie May. She had learned to sail young, her childhood in Ucluelet making her no stranger to the ocean. In rolling seas one day, she climbed the rigging like an expert, winning over the crew and showing them she was a legitimate seafarer. Climbing without asking permission of her captain husband endeared her to the crew even more. After that day, she was one of them. A rum-runner.

And she made the most of this exciting life. One day she dove off the ship’s side, not realizing a school of sharks lurked below the surface on the other side of the ship. The swim was without incident, though perhaps she scanned both sides before her next dip. A photo from the Vancouver Maritime Museum shows a more tender moment: Emmie May on deck, her arms full of kittens. They might have been from the ship’s resident cats, there to keep rats in check.

She spent Christmas of 1932 off the coast of Mexico and the United States in one of several locations nicknamed Rum Row, after the Canadian boats that lined up in a row, ready to unload their cargo of illegal alcohol to be distributed in the United States. In a newspaper article titled “Master Rum-Runner,” Rick James tells of Emmie May being kidnapped by Mexican police and held at ransom in an attempt to catch her husband for American bounty hunters. She somehow escaped and warned him, but how she got away was not noted.

The business of rum-running came into being when liquor prohibition ended in British Columbia years before the United States was allowed to drink freely. In B.C., the sale of liquor was banned from 1917 to 1921; in the U.S., the ban lasted until 1933. This left an opportunity for bootlegging (delivering liquor illegally by land) and rum-running (by water). According to the exhibition A Wild & Wet Coast: Rum-Running During Prohibition, on display until March 31, 2024, at the Vancouver Maritime Museum: “Promise of adventure and riches lured many Vancouverites into the by water trade. For 13 years, high profits fuelled the city’s economy and built key landmarks.” Prohibition left its mark on Canada’s history, with many current liquor laws and alcohol distribution and access systems stemming from this period.

The Malahat in 1927, passing through Vancouver harbour. Photo LM2007.1000.4707 courtesy of the Vancouver Maritime Museum.

The Malahat wasn’t the only boat cashing in on the rum-running business, but it was the biggest. It was a “mother ship,” stealthily supplying liquor and essential supplies to smaller rum-running vessels. Yachts and speedboats with secret compartments and steel-plated hulls (in case of gunfire from coast guard boats) were used to transport the liquor from larger ships to the shore. Some rum-runners painted their boats black and made nighttime missions without lights, hoping they wouldn’t hit floating driftwood.

Rum-running was a cat-and-mouse game between rum-runners and the coast guard. The Malahat moored beyond the range of coast guard ships. The five-masted, 245-foot-long schooner with a hull of douglas fir and space for 50,000 cases of liquor was known as the Queen of Rum Row for its record of delivering more contraband than any other vessel. Despite a top speed of only five knots, it eluded the coast guard for 13 years.

After retiring from carrying illegal liquor, the Malahat transported logs from Haida Gwaii to pulp mills in Powell River and Ocean Falls. In 1944, it met its end. It sprang a leak and sank off Cape Beale, near Bamfield, becoming a statistic of the Graveyard of the Pacific—a stretch of ocean infamous for shipwrecks.

Emmie May’s own personal tragedy struck during her time aboard the Malahat. In 1933, her husband’s appendix burst and he waited too long to see a doctor. Stuart died in a Los Angeles hospital, his wife by his side. Her days of rum-running had lasted only 19 months.

Emmie May (left) and her sister, Phyllis (right), in 1934, prospecting for gold in Nootka Sound. Photo PN13824 courtesy of the Alberni Valley Museum.

Now a widow at 24, she returned to Ucluelet, but her days at sea weren’t over. She bought a 36-foot boat and embarked on prospecting trips up and down the west coast of Vancouver Island with her sister, Phyllis. They took their boat and their gold pans to Nootka Sound and what is now Zeballos. They also worked at the Big Boy gold mine at Herbert Inlet, north of Tofino. The sisters lived at Long Beach and ran a boarding house called Binn’s Barn.

Emmie May remarried, this time to a fisherman named Charles Kerr, whom she met while working as a forewoman at a cannery on the west coast of Vancouver Island. The Kildonan Cannery was on Alberni Inlet between Port Alberni and Bamfield. A village of its own, it perched on pilings above the sea—several large buildings constructed on a wharf. It housed a saltery and a fish-reduction plant, and it canned pilchards and albacore tuna. Emmie May’s boating expertise came in handy when she ferried crews of workers from Port Alberni to the cannery. Photos show her sporting a scarf in her hair and work trousers. Another photograph from the Alberni Valley Museum shows ships lined up off Friendly Cove on Nootka Island during a cannery crew picnic for Emmie May and her workers in 1934.

Then there was the time Emmie May rescued a pilot from the wreckage of a plane. She was a passenger aboard a seaplane en route from Seattle to Victoria. The pilot was flying low due to forest fire smoke and force-landed upon noticing the temperature gauge was higher than normal. After the passengers and pilot exited onto the pontoons, a fire broke out. Emmie May helped a non-swimming passenger into a boat and then swam through the frigid, choppy waters to retrieve a rowboat. The pilot gave up trying to douse the flames and climbed into the rowboat. Minutes later, the fire reached the gas tanks and the plane exploded. For her bravery, in 1934 Emmie May received a Bronze Lifesaving Award.

Realizing the drinking and partying lifestyle wasn’t for her, Emmie May left the fish cannery and moved to Bellingham. That was where she met her last husband, Fred Beal, a logging contractor who ran a sawmill. She died in 1994 in Deming, Washington, in the company of her loving sister, Phyllis.

Emmie May kept diaries of her thrilling West Coast life, though some pages were torn out. But who could blame her? Anyone with a life as exciting as hers surely held a secret or two.

Read more local history stories.