Editors Marita Dachsel and Nancy Lee have collected dozens of personal essays about the relationships that writers and artists have with knitting, crochet, embroidery, weaving, beading, sewing, quilting, and textiles. Sharp Notions: Essays From the Stitching Life is filled with colour photographs and moving essays such as “The Carole Quilt” by Eliane Leslau Silverman, reprinted here.

We swim in the Salish Sea year-round. In wetsuits, face down with masks and snorkels, we swim every season, each Sunday at least and usually once more during the week. We are never fewer than two and sometimes as many as twelve women. Yes, the water is cold, but it is clear, and in our gear, hearing our own breath, we become part of the ocean, joining the busy crabs, the quiet purple or aqua sea stars, the eel grass, the undulating iridescent kelp. We leave behind the complicated realities of our lives. Anxieties about demanding work, personal relationships, the planet, and our beloved children or grandchildren diminish as we swim through icy salt water. Often, we reach an almost meditative place, lost within and supported by the ocean. She is not exactly our mother, as she is indifferent to us, and yet she nourishes us with profound challenges of strong current or wild chop and the deep peace of repetition, our arms and legs steadily working. She holds us up while we do our part, squeezed into wetsuit gear from head to toe, tight and restrictive yet also freeing, since without it we could not survive the low water temperatures. We see life under the surface and become part of it.

We have swum together for nearly twenty years. A few members of the group have moved away; new people join us. We live on Salt Spring Island, off the coast of British Columbia, between Vancouver Island and the mainland. How could we not swim, we whose element is the salt water, when we live on a small island? We call ourselves the Salt Spring Seals, a name we came upon early, laughing at ourselves and yet loving our capacity to brave the ocean. We are clumsier and noisier than the actual seals, who sometimes observe us, even dance underneath and around us, and our gestures are heavier—the crawl or the breaststroke—but we are amazed as we call each other over to see an opalescent nudibranch or the return of a chunky purple starfish. Black and sleek as the seals in our gear, our bright-blue or yellow fins, our pink or green plastic snorkels add a note of the earth world we inhabit, remind us that we cannot live in this element forever but must clamber back to dry land, return to the tug of gravity.

Back on land, we struggle out of our wetsuits, boots, gloves, hoods. Snorkels and fins shed. We sometimes need each other’s help with zippers, or with pulling at the ankles of our suits. The neoprene sticks to our skin as if we were vacuum sealed. Even the sleeves sometimes need help coming off, especially since we suffer more shoulder injuries or experience stiffness as we age. Twenty years is a long time. We share tips about gear, about the tides, about the weather that may be changing. Maybe more rain; snow, even. There is a photo of the two oldest of us, me and Ellen Mae, in our midsixties fifteen years ago, standing at Vesuvius Beach in our wetsuits, in the snow. We talk about past swims. “Diana, do you remember the time we sat on this bench watching the snow front from Vancouver Island coming toward us like a solid white curtain?” We always discuss the swim we have just experienced, forty-five minutes long in dead winter, over an hour in high summer. Anne says it isn’t even worth getting into the gear for less than an hour. The suits are tight, the winter suits heavy. We joke that putting on the gear is half the exercise; even worse is getting out of it.

No two swims are ever the same; the light shifts, the tides change, the temperatures always surprise.

Finally, wearing clothes that we can slip into modestly, we have our tea, always Bengal Spice, and crystallized ginger, because it takes the salt taste out of our mouths and warms our insides. Newer members bring baked treats and occasionally Lay’s potato chips. That’s a great occasion. We sit on logs, huge rocks, or benches, depending on where we have swum, and discuss the day’s swim—what we saw if it was clear, or how murky it was. The ocean never disappoints us. We have sea stars and anemones, rushing schools of small fish and beautiful grasses that let us know by their bend how fast the current is flowing. Seals sometimes make eye contact; we are in love with them. On a few occasions, we have seen sea lions, way too close. They are probably benign, but even a little curiosity from an eight-hundred-pound creature is daunting. No two swims are ever the same; the light shifts, the tides change, the temperatures always surprise. The wind, the chop … so much to talk about. We have become friends, even Seal sisters. We know a lot about each other: birthdays and favourite cakes, diseases and surgeries. After I recently had an operation, the others brought me dinners, calling themselves Seals on Wheels. We pass books around. We pride ourselves on the good food we serve at potlucks. Twenty years, for some of us, of being with each other and the Salish Sea.

Late last summer, one of us, Carole, suffered a terrible event. Her son Tony, not much older than forty, died in a car accident. He was her beloved redhead. Married to Caitlin, he had two small children. The enormous loss of an adored man was evidenced by the outpourings of feelings and generosity to his family. His death left a great big hole in many hearts. Carole spent some months afterward in Vancouver with his young family, consoling and grieving at the same time.

The magnitude of the event left us all shattered, deeply saddened, and vulnerable. We knew that loss lurked everywhere. But we swam. And we pondered. What could we do for Carole? Not much—that kind of grief is so personal, the loss incomprehensible. Six months after the death, Pat proposed that we make a quilt, a recognition of Tony’s death, a signal of Carole’s loss, and a representation of our love for her. We’d had occasion in the past to utilize my experience as a quilter: in support of a Seal with breast cancer, one with a hip replacement, another breast cancer, and for celebrations too, like the Sea Capers Parade. A lot happens in twenty years.

The process began in my studio. Knowing twelve Seals would be participating in the project, I picked out five background fabrics so the quilt would have coherence and continuity. I cut them into twelve-inch squares, laid them on my work table, and added many different fabrics to the selection so that each person could pick her own combination of textiles. There was netting and veiling; there were hand-painted and commercial fabrics, in all their beauty and promise. I loved the moments when each Seal came to my studio, sometimes alone and sometimes with a friend, and pondered the textiles for her contribution. It was a moment of beginnings and, for some of us, of trepidation. Seals may be great swimmers, but they are not necessarily needlewomen.

While not every Seal felt she could contribute to the project, the process and the finished piece held a cherished place in all our hearts. Those who contributed their creativity and their labour put their best selves into it. One by one, two by two, they came over and asked questions as they thought about what they wanted to express in their squares. Some of them returned for more fabric or more embellishments. Many of us talked on the phone, working through ideas. Some of the sewers and makers found it an awkward and difficult process; others felt at home and familiar with creating with textiles. But deep thoughts about loss, empathy for Carole’s grief, and excitement at creating beauty—everybody had those.

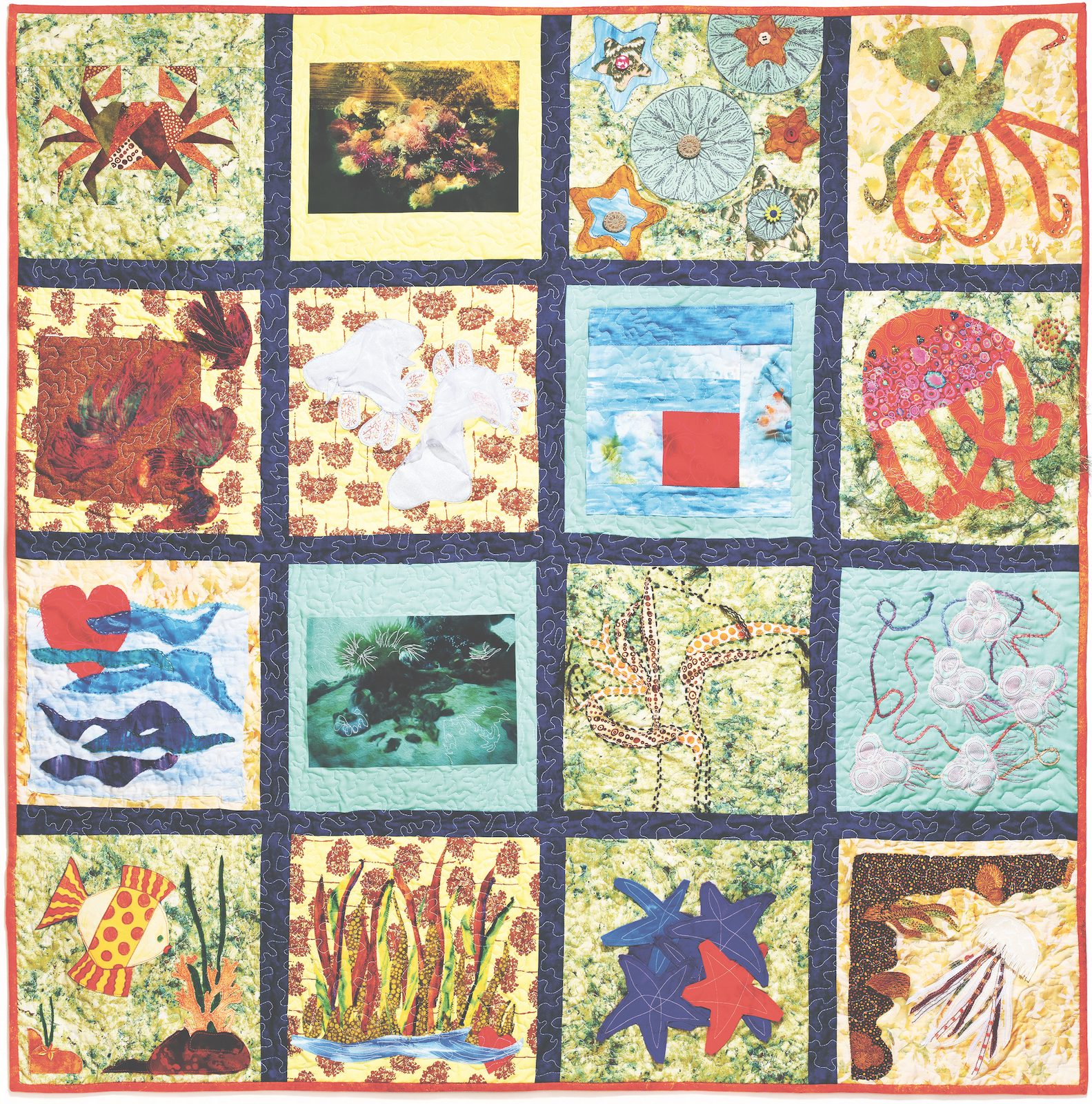

Little by little, the finished twelve-inch squares came back to my studio. And, interestingly, not a single piece referenced Tony’s death or a theme of loss. Instead, they spoke of vibrancy, beauty, and our love for the ocean. Of the water and the ocean floor, our familiar home. Octopuses adorned with sequins, grasses couched with wool and silk and moving with the current, a Dungeness crab carefully pieced. One heavily embroidered maroon kelp bed, and another swaying, outlined in careful stitches of brown wool thread. Sea stars, purple and red, nestled in a happy clump deep within the crevice of a rock. Two red octopuses adjoined each other, one an abstract representation of the creature in tropical waters, its neighbour decorated with tiny coral beads. A ubiquitous moon jelly, translucent and deceptively sweet, and an adorable French angelfish flirting with the coral, a memory of our several visits to Bonaire in the Caribbean, far from our own very cold water. More jellyfish, their tentacles animated by the current, reproductive organs carefully created by shiny thread embellishing their shimmering domes. Sand dollars, beautified with buttons, positioned next to sea stars, a delicate red heart peeking through the waves. On Anne’s squares of fabric, she’d printed two photographs of anemones and snails taken with her GoPro, which accompanies her frequently, providing a strong contrast to the fine stitchery outlining details of the images. And finally, an opalescent giant Pacific nudibranch, the elegant dancing invertebrate we all love so much, made of transparent folded fabric, raised up and announcing itself.

Salt Spring Seals, The Carole Quilt, 2021. Photo by Janet Dwyer Photography.

We all fell in love with our squares. They were expressions of our very hearts and our whole beings. Each piece was brought to me, held out and handed over by its designer as if it were her first-born. I laid out the pieces on a white sheet, arranging and rearranging them until I had a good balance of texture, colour, and weight. Navy-blue sashing allowed each piece to stand on its own and yet live in unity with the others. I admit to a feeling of reverence when quilting the piece. A quilt made by a community to whom I owe my ocean self demanded fidelity to the group, unlike even the pieces I make for friends and family; each woman had made a square I had to honour. The binding was bright orange, which I chose to remind us of so many losses: our beautiful brilliant orange sun stars, many legged, slowly pulsating on the ocean floor, killed by the growing heat of the water and by a virus. They wasted, their legs turning white before our eyes, before finally disappearing entirely five years ago. Perhaps they will return. Or perhaps not.

Upon the quilt’s completion, a Seal who is a professional photographer took it home and photographed it under studio lights. I missed the quilt’s powerful presence—profound, important, like the ocean itself or like my Seal sisters—when it left my studio. Our first Seal, Diana (I like to call her the mother of us all), reproduced a quotation from each of us on paper to scale with the quilt, representing through language yet another expression of our caring about each other. Each of us signed with a gold pen.

The joyous moment was punctuated and intensified by grief; it always accompanies us humans on land, though it’s sometimes ameliorated in the water.

We arranged a date with Carole when everybody could be there to present her the quilt, without telling her why we would be gathering in her driveway during this difficult time of COVID. We carpooled, as we usually do, thinking to spare the environment, down to the south end of the island, carrying not only the quilt but, of course, snacks and tea—where there are Seals, there is food! The big moment … Carole would be surprised, we knew.

When we had all arrived in her driveway, we called Carole to come out of the house. In winter clothing like all of the rest of us on that chilly afternoon, she looked a bit bewildered, but smiled in her usual welcoming way at all of us standing in a circle. Two of us lifted the folded quilt from the trunk of my car and slowly opened it, raised it up high. Silence first, then tears all around. We explained the process, with its sewing challenges and its joyful creativity, so that she could be part of it. She accepted the gift graciously and later created a space for it in her small house, offering it an iconic place akin to an altar, in fact. She joined in a bit tentatively and then wholeheartedly as we talked about the ocean, reminisced about our many years together, ate, laughed, cried, froze in the cold, and felt renewed. The joyous moment was punctuated and intensified by grief; it always accompanies us humans on land, though it’s sometimes ameliorated in the water. The water supports us. The ocean nurtures us.

Sadly, the story doesn’t end there. A few months later, Catherine’s daughter Michelle, also only in her early forties, died unexpectedly in her apartment in Vancouver. The loss begins again, or continues, as grief must. We have already wondered what we might do for Catherine. It is too soon to know. Plant a tree, maybe, or bring weekly desserts? We must live with the knowledge of tenuousness and fragility for a while still. We will see what we choose to make for her. Meanwhile, we swim on, and as the water warms up, our hearts may begin to thaw.

“The Carole Quilt” was written by Eliane Leslau Silverman. Reprinted with permission from Sharp Notions: Essays From the Stitching Life, edited by Marita Dachsel and Nancy Lee (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2023). Read more stories about community.