This story is the sixth in our series on the hidden history of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. Read more here.

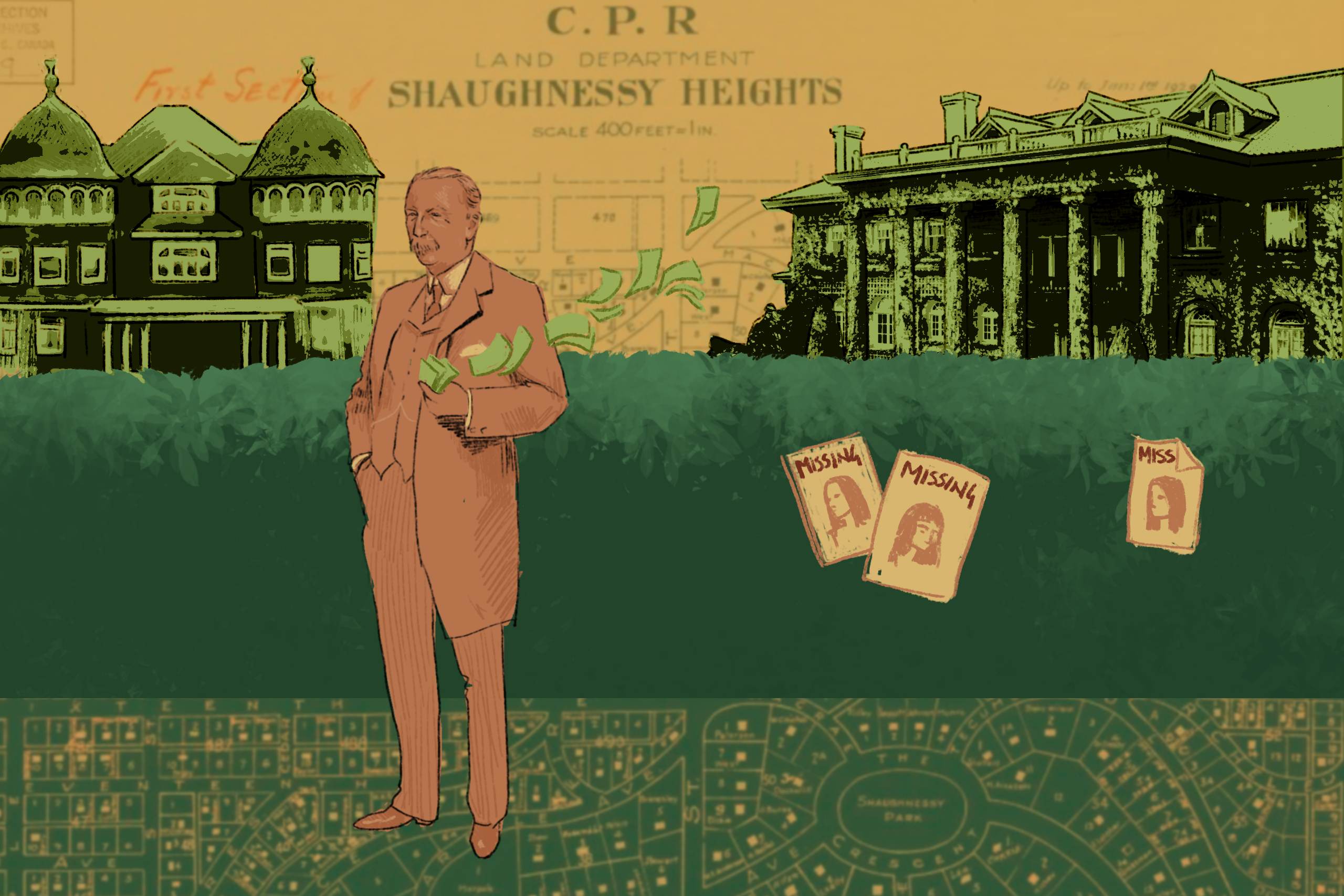

This past summer, a realtor named Randy Vogel was caught on video removing posters from lampposts on a busy stretch of Granville Street that bisects Vancouver’s most exclusive neighbourhood, Shaughnessy. The posters sought information about the death and disappearance of Chelsea Poorman, a 24-year-old Cree woman whose body had been discovered that April by a construction worker in the backyard of an empty mansion on West 36th Avenue and Granville. Poorman had been missing for over a year and a half, but police concluded that the young woman’s death was not considered suspicious. Her family felt differently. The realtor probably didn’t think his absence of human decency would cost him his job.

Vogel’s disregard for Poorman’s family was exhibted in broad daylight. Outsiders might get the impression Shaughnessy residents are used to doing whatever they want. The area’s winding streets, hedge walls, and keypadded gateways—not to mention its dearth of residential density and commercial space except along its edges—discourage prying eyes. Over the years, the impunity afforded by privilege and privacy has made it the site of intrigue and conflict (and the occasional gang-related murder).

Shaughnessy Heights, named after Canadian Pacific Railway president Thomas Shaughnessy, began in 1907 as a prime subdivision offered by the CPR, just south of the city limits on West 15th Avenue, between Granville and Oak streets. Its pinwheeling streets thumb their noses at the grid structure imposed on the rest of the city, spiralling around Shaughnessy Park (better known as The Crescent and home to 47 rare species of trees). New homes built in the neighbourhood had to cost at least $6,000, six times the price of the average home in Vancouver, on lots more than twice the standard size.

CPR executives built there—their surnames, such as Osler and Angus, bestowed on its streets—and they were soon followed by the city’s upper crust, who fled the West End and Fairview for a neighbourhood with newly built amenities such as tennis and lawn bowling courts and a golf course (later, the site for VanDusen Botanical Garden). In 1911, the success of the initial development prompted a westward expansion to Arbutus Street. As Canada entered the First World War in 1914, Shaughnessy was home to 243 households. Successive southward expansions to West 33rd and then West 41st avenues were known as Second and Third Shaughnessy, respectively.

One of First Shaughnessy’s most iconic homes, Hycroft Manor, was built by the president of the Fraser River Lumber Company and member of Parliament Alexander McRae and his wife, Blaunche. Perched at the foot of the neighbourhood with a view of the city, Hycroft announced its grandeur with a neoclassical façade. Behind it were 30 rooms, including a ballroom and 20,000-bottle wine cellar. It’s now best known as a popular backdrop for wedding photos.

Like Hycroft, Glen Brae was commissioned by a Scottish magnate, lumber and land baron William Tait. Constructed in 1910, the 16,000-square-foot mansion featured twin domed turrets and one of the province’s first elevators. After Tait’s death, the house fell into decline and was rented for $150 per month by the Canadian Knights of Ku Klux Klan in 1925. The group proudly marched from downtown Vancouver to their lavish new digs along Granville Street. The residence would serve as a site for a kindergarten and private hospital before taking on its present incarnation as Canuck Place, the children’s hospice sponsored by the Vancouver Canucks NHL team, in 1995.

Another notable home visible to commuters heading downtown is located at 3338 Granville. Built in 1913 by Dr. W. Brydon-Jack, who would become a coroner for the city, the Tudor-revival-style mansion has been the consulate general of China and the location of regular protests by the Falun Gong spiritual movement for more than two decades.

Early in Shaughnessy’s history, a relatively modest home on Osler Street was rocked by the 1924 murder of Janet Smith. A century before Chelsea Poorhouse’s body was found, the body of a 22-year-old Scottish nanny was discovered by the property’s other domestic, a Chinese houseboy named Wong Foon Sing, with a gunshot wound to her head. Although the death was initially ruled a suicide and Smith’s body quickly embalmed before an autopsy could be performed, suspicion fell on Wong, who was kidnapped—with the tacit permission of the attorney general—and tortured for six weeks by a group of prominent Vancouverites dressed in Ku Klux Klan robes. Wong was subsequently tried for murder and acquitted. In the ensuing years, speculation has pointed to the involvement of Smith’s drug-smuggling employer, Fred Baker; Jack Nichol, the playboy son of Lieutenant Governor Walter Nichol; and one of the McRae daughters of Hycroft Manor, with whom the younger Nichol was romantically involved.

In the decades since, as Vancouver real estate prices waxed and waned, Shaughnessy’s high-priced and expensive-to-maintain homes felt the brunt of market fluctuations. In the 1930s, according to Daniel Francis’s Becoming Vancouver, over 250 properties were repossessed. Other homes were repurposed. In 1942, for instance, McRae donated Hycroft Manor to the Canadian government, which used it as a hospital for wounded veterans. It was later purchased by the University Women’s Club of Vancouver (who had to pay in full because women were not allowed to hold a mortgage at the time). The Rosemary, a 14,000-square-foot Tudor-style mansion built in 1913, was a rooming house and then a religious retreat operated by the Congregation of Our Lady of the Retreat in the Cenacle.

With the city’s homeowners currently on an unprecedented two-decade winning streak of rising real estate prices, Shaughnessy residents have even less reason to cry poor. At $112,000 in median annual household income, the area is the city’s wealthiest. According to city data, its population is also aging and shrinking. Meanwhile, transnational wealth has brought in satellite kids with astronaut parents returning from Asia. Squatters have taken advantage of some Shaughnessy mansions bought up by investors who live in them infrequently.

“There are very few people on the sidewalks of Shaughnessy. Those who live there glide in and out of driveways in electric cars that make little more than a hum,” notes essayist Erika Thorkelson, who lives in a rental apartment near Shaughnessy. “When I do pass someone, we share a look of surprise as if we had both forgotten other people were real.”

One Shaughnessy home that was occupied belonged to Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou, who lived there under house arrest between 2018 and 2021 while fighting extradition to the United States for wire-fraud charges. Press photos of Meng leaving her $13.7-million Shaughnessy residence (Meng also owned a smaller house in Dunbar) for court appearances demonstrate that justice is served first class in Vancouver’s wealthiest neighbourhood.

Read more Vancouver neighbourhood stories.