When John Bjornstrom escaped from a Kamloops correctional facility with three months left in his sentence for breaking and entering in 1998, he captured the public’s imagination as a fugitive in the B.C. Interior. Known as the Bushman of the Shuswap, he evaded the RCMP for three years through an elaborate series of hideouts in the woods, where he lived in a well-stocked cave.

He also annoyed local cottage owners, whose homes he regularly stole from (and who were not appeased by the apologetic notes he’d leave behind). When a group of houseboaters stumbled upon his cave several months after he’d been recaptured by police in November 2001, their discovery made headlines across Canada. After serving the rest of his sentence under house arrest, Bjornstrom returned to trucking, volunteered at the Salvation Army’s drop-in centre in Williams Lake, and even ran (unsuccessfully) for mayor in 2014. He died suddenly in 2018 at age 58.

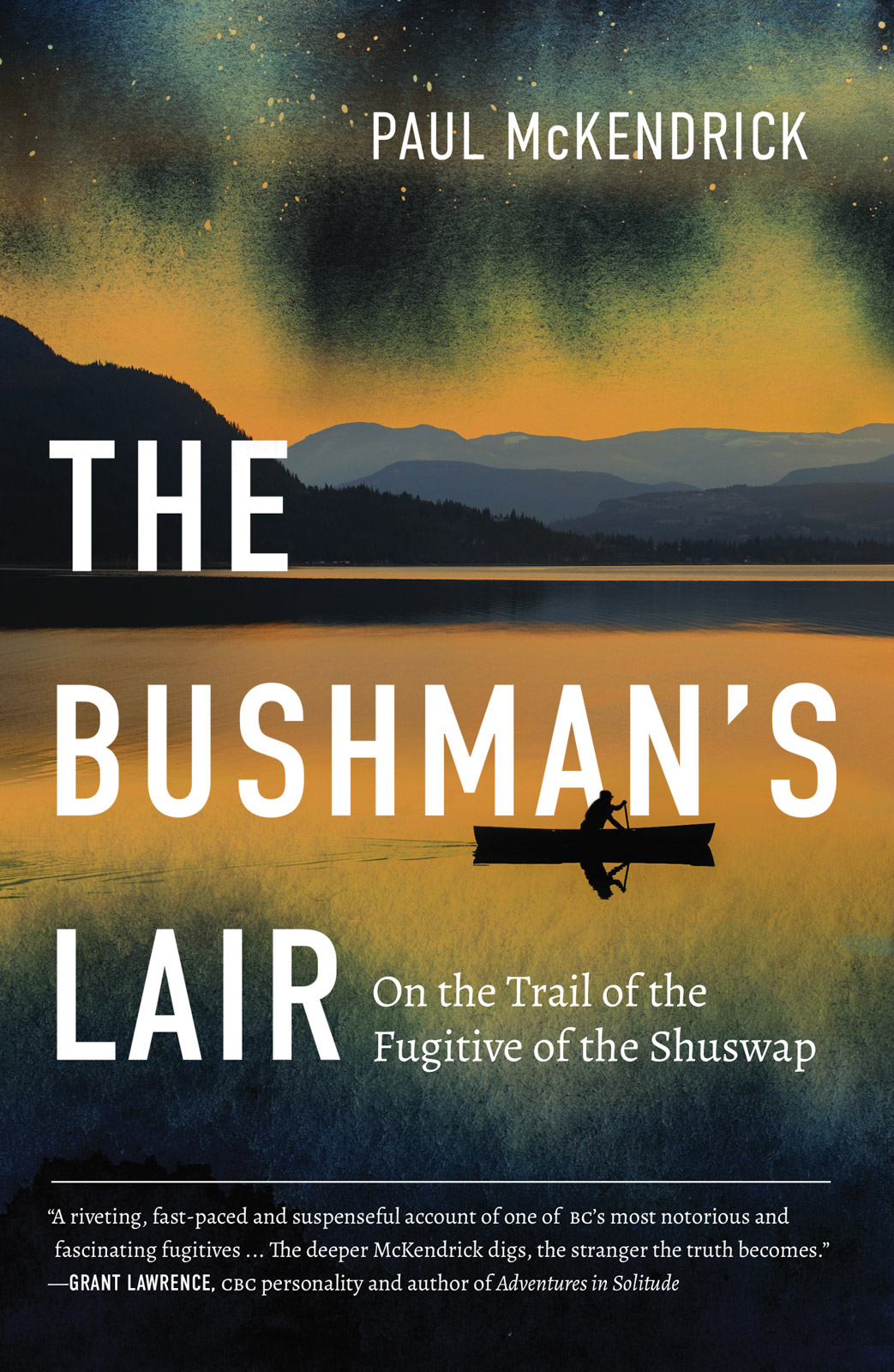

This excerpt from Paul McKendrick’s new book, The Bushman’s Lair: On the Trail of the Fugitive of the Shuswap, is reprinted with permission from the publisher, Harbour Publishing.

Submerging a canoe is not very difficult: it can be tilted to one side to let the water pour in. That leaves it floating barely below the surface, assuming it’s been constructed from materials that are sufficiently buoyant. If one desires to go further and actually sink the canoe, a dozen or so grapefruit-sized rocks should do the trick. The boat will gradually settle to the bottom. It may still be visible, however, so if the ultimate objective is to conceal its presence, it helps to paint it so that it’s indistinguishable from whatever else rests below.

Retrieving a sunken canoe is more burdensome. First, it must be located, which can be hindered by a steep drop-off below the surface or a camouflaging coat of paint. Then it can be fished out with something like a long pole with a hook at one end or, if a suitable jig is unavailable, dragged to the surface by hand. Once the rocks are removed, there’s the awkward process of hauling it ashore or finding a sturdy platform to rest one end on, then raising the other end above the water and corkscrewing the boat in midair gracefully enough that no water re-enters before it’s returned to an upright and ready position.

The Bushman had carried out the process many times. Although his five-foot-four, 200-pound frame didn’t grant him a long reach, his stoutness did facilitate heavy lifting. He hadn’t found a way to do the job without getting wet, but the process had become as mindless as driving one’s car out of the garage. So inconvenience was not top of mind as he retrieved his canoe from the lake bottom one frigid day in November 2001. It helped that it was daytime—usually he operated under the cover of darkness. But what really kept him from dwelling upon the task was concern that he might be about to walk—or more precisely, canoe—into a trap.

The following summer, near that same spot, a group of houseboaters pulled their rented floating homes, Yachts of Fun and Peat’s Pride, up to a remote beach on British Columbia’s Shuswap Lake. The boats were staked to the ground to make sure they stayed put for the night. The beach was equipped with fire pits, but the houseboaters hadn’t brought firewood. Collecting deadwood was prohibited—this beach was within a newly formed provincial park—and a sign on the beach indicated the fine was somewhere in the vast range of $86 to $1,000,000 (the upper end presumably reserved for those pillaging more than a few sticks for a fire).

The law-abiding boaters appointed a three-man crew to harvest fuel farther south down the lake, past the protected area, and they set out in a smaller boat that had been towed behind one of the motherships. They hoped to find large pieces of deadwood floating in the water; this would serve the dual benefits of burning longer into the night and removing the boating hazard. But the lake’s waterline had receded in the summer heat, exposing more of the craggy shoreline and leaving less deadwood in the water, so they had to go ashore instead.

Above them rose steep and seemingly impenetrable slopes clad in spruce, fir, cedar, and hemlock—an unlikely location for signs of human activity. So they were surprised to see that the receding water had exposed a black hose that snaked under rocks and led up into the bush. They decided to follow it and discovered a faint trail that meandered from above the rocky shoreline and up a couple of switchbacks. They came to what looked like a small wooden shed built into the steep, mossy hillside. It was framed with two-by-eights that didn’t yet display the silvery patina of years of oxidation and sun exposure. Fringes of vapour barrier could be seen at junctures in the framing. When the foragers opened the door and poked their heads inside, they were greeted by the beginning of a passageway that disappeared into darkness.

Conveniently there was a light switch just beyond the entranceway, and it illuminated more of the dank corridor. The walls, which looked hastily assembled and suspect in their ability to resist a cave-in, were lined with wood framing intermeshed with wiring and cords. The floor was mostly bare earth, strewn with buckets, pipes, and boards. Near the entrance was a smaller portal with a door open just enough to admit the black hose from the lake. The outside of the door was camouflaged with branches held in place by spray insulation. Binoculars hung nearby, presumably used to scan activity on the water.

Farther along, the walls were adorned with snowshoes, fishing nets, and other paraphernalia hanging from hooks, and beyond that the passageway broadened to about 15 feet wide to accommodate a kitchen. Plywood shelves were lined with jars of ground coffee, vegetable oil, sugar, salt, and popcorn seeds. There were pots and pans and cleaning supplies, including a fresh box of SOS pads. An empty Kraft Dinner box lay beside a well-used two-burner camp stove. Shelves adjacent to the kitchen held a bank of at least 10 car batteries interconnected by rusty cables and grounded to a post. A small clothes washer was plugged into the battery bank. Farther along, the passageway was partly obstructed by hundred-pound propane tanks that would weigh about 170 pounds when full.

At the end of the passageway, about 30 feet into the rock, the cave pivoted to the right and expanded into a roughly 13-by-13-foot chamber. The space was framed in and protected from moisture by layers of vapour barrier with insulation sandwiched between. An elevated plywood frame supported a regular bed mattress upon which lay an assortment of blankets and clothing. Storage units fashioned from plywood surrounded the bed. Wiring that fed into the bedroom was connected to various lights, a computer, and a radio. Reading material was scattered about, including a newspaper opened to an article on Osama bin Laden. In the corner stood a small bird cage, though nothing stared back at them from it.

The boaters asked themselves whose abode it could be. An especially private hermit? Someone with an unorthodox idea of a fishing lodge? Or perhaps someone more menacing who could return at any moment? They didn’t linger to find out. They returned to their group to tell them of their discovery and informed the manager of the houseboat rental company, who had shown up to fix a faulty battery in one of the boats.

The manager needed few details to identify the occupant: “It’s the home of the Shuswap Bushman!”

Read more book excerpts from local authors.