Fifty years ago this month, the enemy came to town and we cheered like crazy.

Soviet premier Alexei Kosygin visited Vancouver for two October days in 1971. He was greeted at the airport by a smiling W.A.C. Bennett, a conservative politician known for his antipathy to Communists.

The British Columbia premier invited his Soviet counterpart to join him in a suite at the Hotel Vancouver, where the two bantered (through a translator) like long lost comrades. Bennett gave the Communist boss a pair of cuff links marking the province’s centennial of joining Confederation, as well as a set of coins minted in Ottawa to commemorate the same event.

The two politicians then attended a hockey game at the packed Pacific Coliseum. Scalpers made a killing, as one red seat normally priced at $6.50 went for $32 (about $217 today). When Kosygin was introduced by the public-address announcer, a few scattered boos were quickly overwhelmed by growing applause that swelled into a standing ovation.

Before the puck was dropped, Kosygin met briefly with team captains Henri Richard of the Montreal Canadiens and Orland Kurtenbach of the hometown Canucks. “From his conversation,” Richard said, “he obviously knows hockey.” The Soviet let it be known he thought Soviet players were superior to NHL players, a proposition that would be tested in the following year’s famous series, which ended with “Henderson has scored for Canada!”

Kosygin, who was accompanied by his daughter, Lyudmila Gvishiani, stayed for two periods. If a Soviet leader being cheered by a Western sports crowd was disorienting, at least the hockey game unfolded predictably with the Canadiens crushing the Canucks, 6-0.

The next day, Kosygin toured a particleboard plant, ate lunch aboard the liner SS Prince George in Vancouver Harbour, and then gave a speech to 900 diners at the Hotel Vancouver.

Heavy security surrounded the Soviet premier at all times. More than 50 city policemen joined RCMP officers and Soviet security men to protect Kosygin. The few protests in Vancouver against the premier were orderly. A few days earlier, however, a 27-year-old Toronto hairdresser and Hungarian emigree named Geza Matrai accosted Kosygin on Parliament Hill, jumping on his back while shouting, “Long live Hungary! Down with Russians.” He was pulled off by RCMP agents before causing any physical harm.

The scenario captured the imagination of a Vancouver newspaperman. Thomas Grant Ardies was a blue-eyed lothario with a lady-killer mustache who had worked as a labourer, an iceman, and a fruit picker before being hired as a $14-per-week copyboy at the Vancouver Sun at age 16. He married at 23 and remarried at 31, his second bride the daughter of a prominent hotelier.

Ardies rose through the newspaper’s ranks, in his words, from “general assignment reporter to columnist to editorial writer to giving up.” He quit to work on a newspaper in Hawaii before being hired as a political aide to the governor of Guam. While on a hiatus in Mexico, where he lived in a caravan grandly dubbed Rancho Canada in the town of Alamos in the state of Sonora in northwest Mexico, Ardies cranked out a potboiler about Soviet perfidy with the title Their Man in the White House. The hero was a flawed James Bondian fellow by the name Charlie Sparrow, who also happened to live in a caravan in Alamos. The thriller was published a few months before Kosygin’s eight-day trip to Canada.

The attack on Kosygin and the incongruity of the RCMP protecting their Soviet enemy sparked in Ardies the plot for another adventure. The book, his fourth, was titled Kosygin is Coming, about the RCMP’s desperate efforts to thwart an assassin.

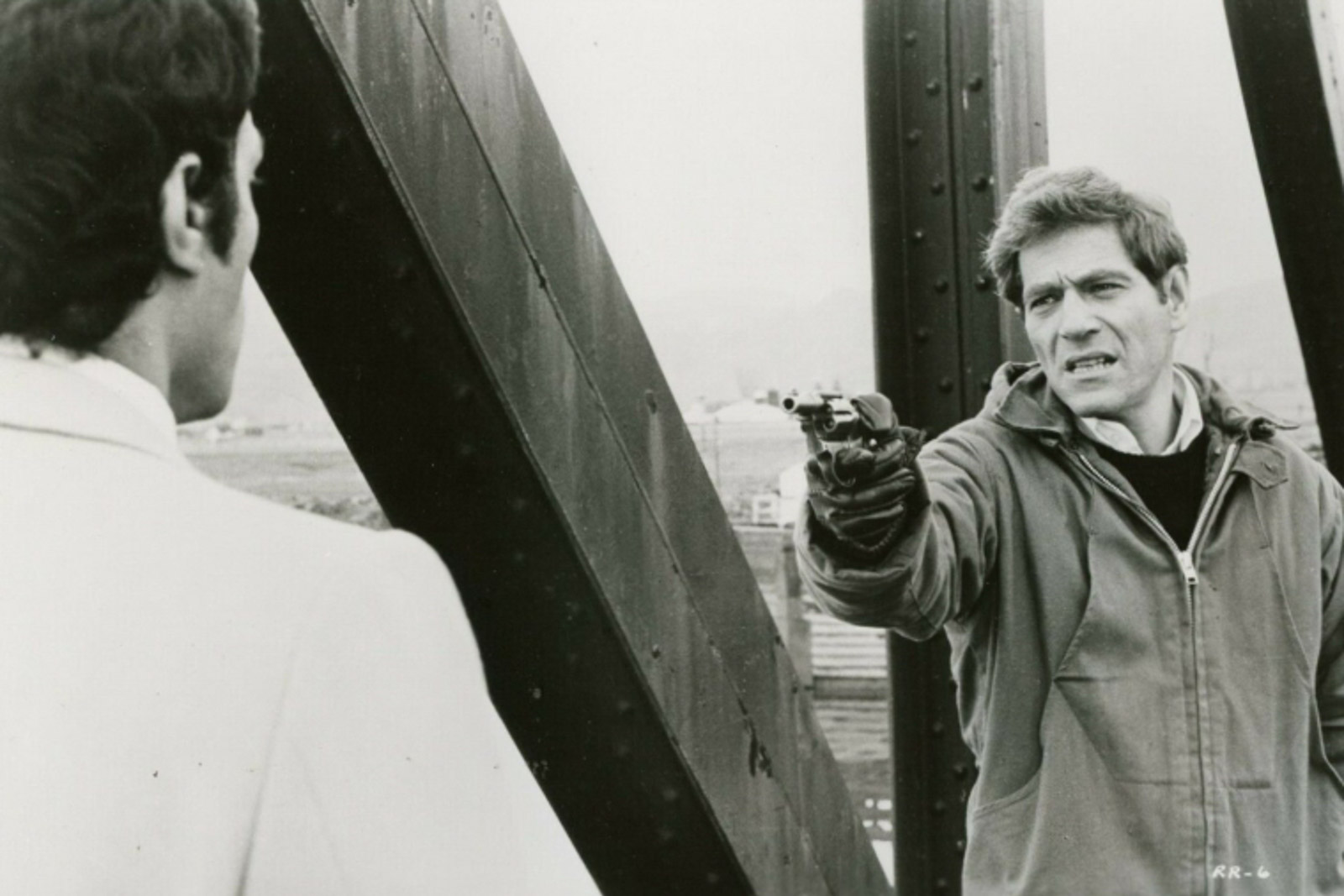

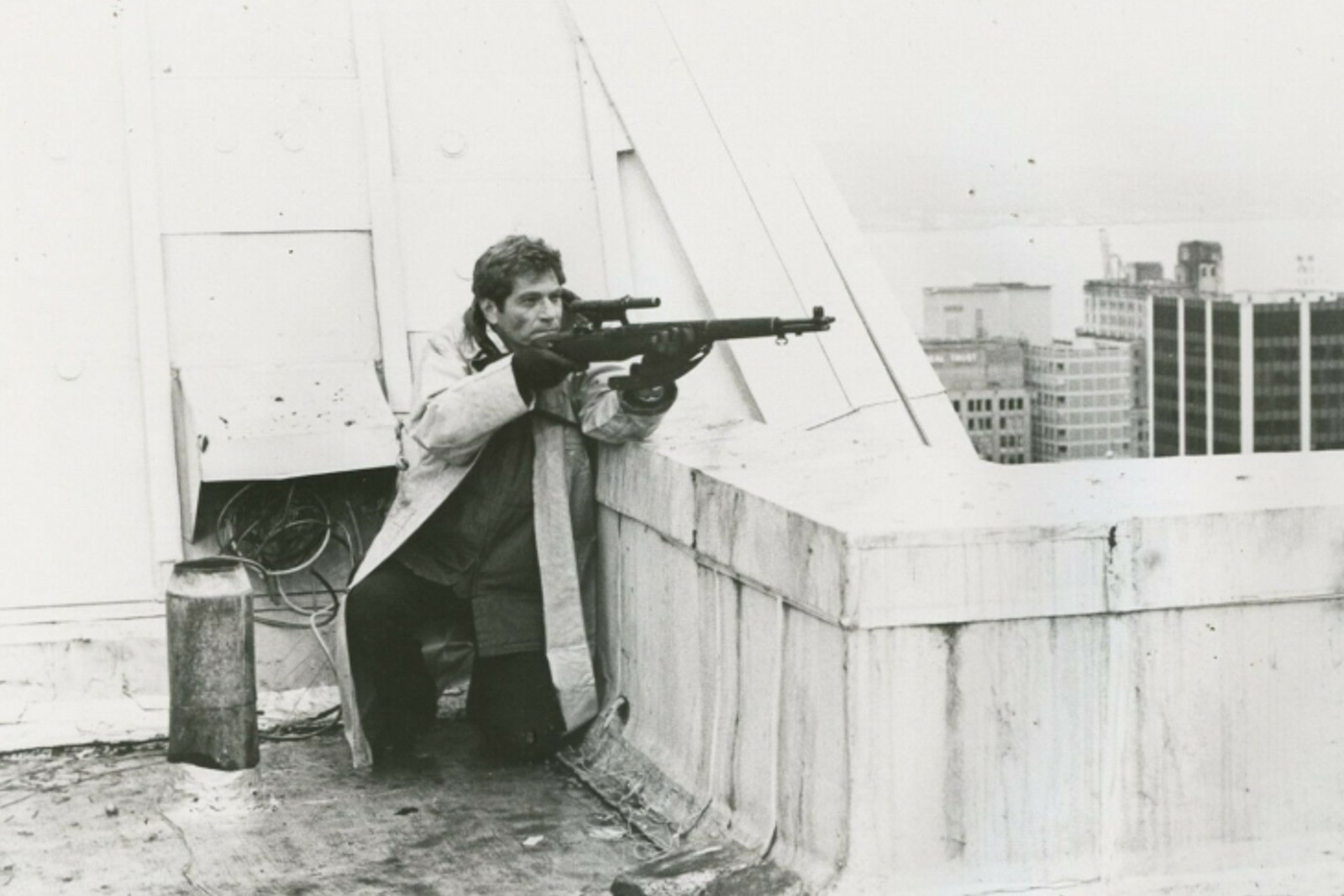

The book was quickly optioned as a movie by Bulldog Productions, a company founded by English impresario Sir Lew Grade. George Segal signed on to portray RCMP Cpl. Timothy Shaver, who becomes embroiled in a desperate bid to thwart the assassination of a foreign dignitary.

The original scriptwriter, Arnold Margolin, hot off the success of the television show Love American Style, came back with a draft called Estimated Time of Arrival. (His younger brother is Stuart Margolin, who played James Garner’s former cellmate Angel in the Rockford Files before spending years living on Salt Spring Island. Both Margolin brothers now live in West Virginia.) A script doctor, Stanley Mann, was then called on to rewrite it. The movie got a new title: Russian Roulette. Ardies even got credit as a co-writer.

Ardies hated the movie (which can today be watched in its entirety on YouTube). He was joined in his opinion by reviewers.

Today, the movie is remembered for its closing scene, a dramatic shootout on the sloping, copper green roof of the Hotel Vancouver. While filming took place around Vancouver, the novelist formed a company called LTA (Little Tommy Ardies) to solicit funding from businessmen for productions in which writers and artists would have more control of the final product.

“I’m not an intellectual,” Ardies told Roy Shields of Southam News Services during the shooting. “I’m a common man who wants to reach the people. I’ve found that 60,000 people might read Kosygin is Coming, but as a movie it will reach 100 million.”

Ardies was convinced Vancouver was positioned to become a first-class destination for Hollywood movies, offering scenic backdrops including the sea, forests, and mountains, as well as gritty urban and pastoral suburban landscapes. Desert and sagebrush was as close as the Okanagan. Ardies insisted the city would become a hub for Hollywood filmmaking, as productions would be lured across the border to take advantage of a new federal tax credit.

“This is where it’s at,” he insisted.

He was correct, of course, but his prediction of Hollywood North did not come to fruition for many more years.

Filming for Russian Roulette took place in the fall, leaving a dreary impression of the city on film. It can still be fun to spot sites before the post-Expo 86 boom altered the city’s landscape.

Ardies soon after moved to California, where he continued to write thrillers and detective potboilers under the pen name Jack Trolley. The hero of his new series was a San Diego homicide sergeant Tommy Donahoo. There was another marriage in 1983 and yet another in 1987.

Back in Vancouver, Ardies remained a journalistic legend. More than a decade after he had left the Vancouver Sun, the newspaper published a lengthy account of one of his exploits. Back in 1959, an anonymous Sun staffer created a fictitious character by the name Prince Stefan Franz von Beriot, a “madcap moneyed Austrian.” The playful deskers kept up the jape, slipping the playboy prince into a column featuring statesmen and starlets. The made-up character was celebrated by students at the University of British Columbia who were excited to be in on the joke. The students’ enthusiasm led the newsmen to fear discovery of their creation, likely a fireable offence, which convinced Ardies to slip the shiv into the prosperous prince. As Ardies recalled in the Guam Daily News nine years later, he wrote an obituary for the poor prince, reading, “Dead: Moneyed, madcap, daring Prince Stefan Franz von Beriot, the Austrian nobleman whose antics made him the toast of Europe, of cirrhosis of the liver, while on a holiday junket in Rome.”

(The real faux death report did appear in the Sun on June 9, 1959, though it was plainer than Arlies’ later recreation. It cited only a death by unknown causes in Vienna.)

In recent years, the novelist’s taut, newspaperese prose and fast-paced plots have found a new audience. His works were still available online when he died in California last year.

Unfortunately for the writer, his prescience mostly went unnoticed in his lifetime. Kosygin Is Coming presaged the 1970s assassination obsession (Day of the Jackal and Taxi Driver on the big screen, the shooting of George Wallace and the attempts on U.S. President Gerald Ford by Squeaky Fromme and Sara Jane Moore in real life), while his second thriller, This Suitcase is Going to Explode, captured anxieties about dirty bombs and atomic weapons available to rogue players. Though he was miles ahead of his peers in understanding the future of Hollywood North, he was too early to cash in.

It should also be noted that Ardies wrote a thriller in which Charlie Sparrow tries to stop a reclusive billionaire from trying to save the world by killing masses of people with a deadly virus. The book was titled Pandemic. He was alive to see the arrival of a true pandemic last year, the final chapter of which has yet to be written.

Images courtesy of Bulldog Productions. Read more history stories.