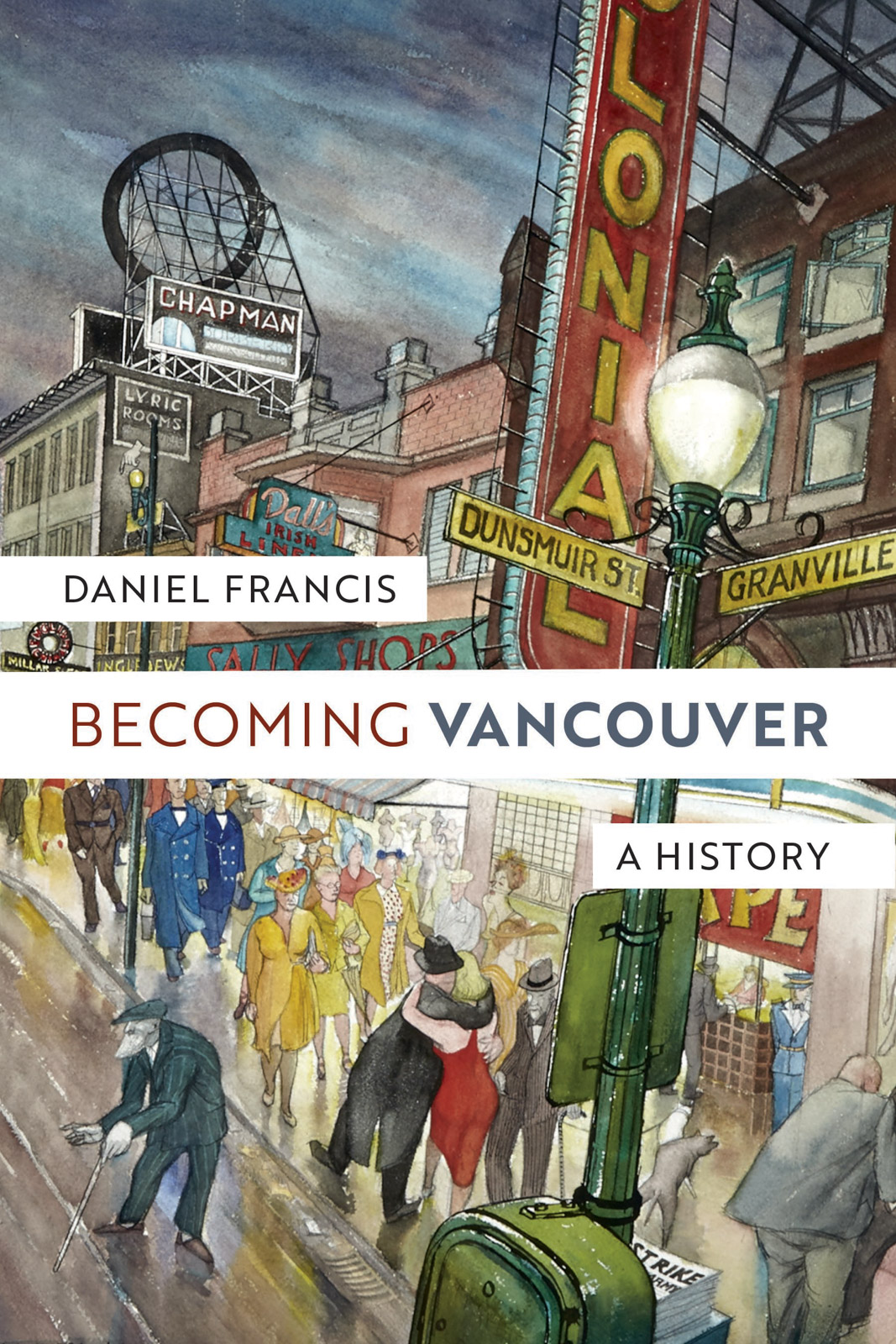

In his new book Becoming Vancouver, released this month from Harbour Publishing, award-winning historian Daniel Francis traces the birth of a city, from early habitation by the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations, through a rough and tumble history of mills and speakeasies, to the present day hubbub of real-estate speculation. In this excerpt, Francis tells the story of how a shocking act of police brutality set the scene for the chief of police’s investigation for corruption.

Much was changing in the city as it went through its postwar remake, but one thing that remained the same was the inability of the police force to avoid scandal. As the Sun pointed out, the average tenure for a police chief in Vancouver was only four years. When Walter Mulligan became chief in 1947—at forty-two years old he was the youngest chief in the force’s history—he was supposed to be another new broom that swept it all clean. But the old patterns asserted themselves. In 1952, for example, the force was embroiled in highly public accusations of racist brutality.

Police chief Walter Mulligan.

Early in the morning of July 19, a fifty-two-year-old stevedore named Clarence Clemons got into a scuffle with police at the New Station Café on Main Street. The New Station had a reputation as a lively afterhours joint close to Hogan’s Alley. “It was world-renowned,” affirmed Dorothy Nealy, a neighbourhood resident. “People would come from all parts of the city, used to come off the ships, the merchant seamen, and they’d stop you, ‘where’s this New Station?’ You ordered something to eat, and you had your bottles with you, and you drank, and you met people and laughed and talked and danced up and down the aisles.”

On this occasion Clemons, who was Black, ended up in a jail cell charged with assault. Complaining of pain and partially paralyzed, he was taken to hospital where doctors could not find anything wrong with him. After his wife bailed him out of jail, Clemons continued to experience serious discomfort. A few days later he lapsed into a coma from which he never recovered. He died the day before Christmas.

The old Vancouver police station, 1956. Photograph by Walter E. Frost, courtesy of the Vancouver Archives.

Coincidentally, on the day of Clemons’s arrest, the Sun ran an article profiling the city’s Black community. According to reporter Bruce Ramsey there were about 700 “negroes” living in the city. While prejudice against them was not as bad as in the United States, wrote Ramsey, many local employers “continue to draw the colour line when hiring.” An exception was the railway, where many of the men in the community found employment as porters and stewards. “The local negro population has given the police very little trouble,” wrote Ramsey, an ironic observation given the outcry that erupted over Clemons’s treatment.

The Pacific Tribune, a Communist newspaper, was the first to take up the case, claiming that Clemons was victimized by police because of the colour of his skin. Human rights activists got involved, demanding that the city police commission investigate. In October, while Clemons lay in a coma, the commission decided there was not enough evidence to pursue the case. When he died, however, an inquest was convened. It opened on January 6, 1953, attracting an overflowing courtroom and front page headlines. The all-white jury heard from more than fifty witnesses, some of whom said they saw police bludgeoning Clemons, others claiming that he was a troublesome drunk who resisted arrest. In the end it was the medical evidence, or lack of it, that led the jury to exonerate the police. Doctors testified that Clemons had a pre-existing degenerative condition of the spine which was aggravated by the scuffle but not caused by it. The Black community remained unsatisfied, but public attention moved on.

Police officers march in the 1955 P.N.E Opening Day Parade. Image courtesy of the City of Vancouver.

More troubling for Chief Mulligan were the rumours of corruption and influence-peddling that swirled around his force. According to the tabloid press, Vancouver was a “Gangland Eden” where officers, including the chief, regularly received bribes from gamblers, bootleggers and brothel keepers. In 1955 the provincial government appointed a commissioner, city lawyer Reginald Tupper, to look into the allegations. For seven months Tupper, grandson of former prime minister Sir Charles Tupper, heard testimony revealing how deeply the rot had spread.

Chief Mulligan’s mistress was among the witnesses, along with various colourful underworld figures and crooked cops. One member of the force committed suicide; another tried to kill himself and failed. Every night listeners hung by their radios to hear journalist Jack Webster give a blow-by-blow account of the day’s proceedings on station CJOR. Mulligan himself was accused of being on the take. Unable to stand the pressure, he resigned his job and decamped for California, where he found work at a flower nursery. Tupper’s report confirmed that the chief had been accepting bribes, but no charges were ever laid.

Excerpted from Becoming Vancouver with permission from Harbour Publishing. Read more local History stories.