There’s a bootleg recording of Joe Strummer and the Mescaleros in Tokyo on January 18, 2000, just after the World Cup. Football—soccer, to us—was very much on Strummer’s mind. In an aside to a bandmate, Strummer weighs in on the virtues of Tony Adams as a captain versus Alan Shearer, then turns to the audience to apologize for the digression. “We’re having a technical conversation on football,” he quips, then paraphrases Bill Shankly: “What did he say? ‘It’s not a matter of life and death. It’s more important!’”

Strummer is no longer with us, but some Vancouver punks remember that his most famous band, the Clash, kicked off their first North American tour not with a concert, but with a soccer game—in Kitsilano, just before the band’s inaugural North American show at the Commodore on January 31, 1979. The Clash also checked out some local music at the Windmill and went to a house party at 509 East Cordova, a site so notorious the Modernettes wrote a song about it.

As Pointed Sticks front man Nick Jones recalls, “It was not just a band coming for a gig and then disappearing afterwards. They were here for very close to a week. For the punks in Vancouver it was a pretty exciting time.”

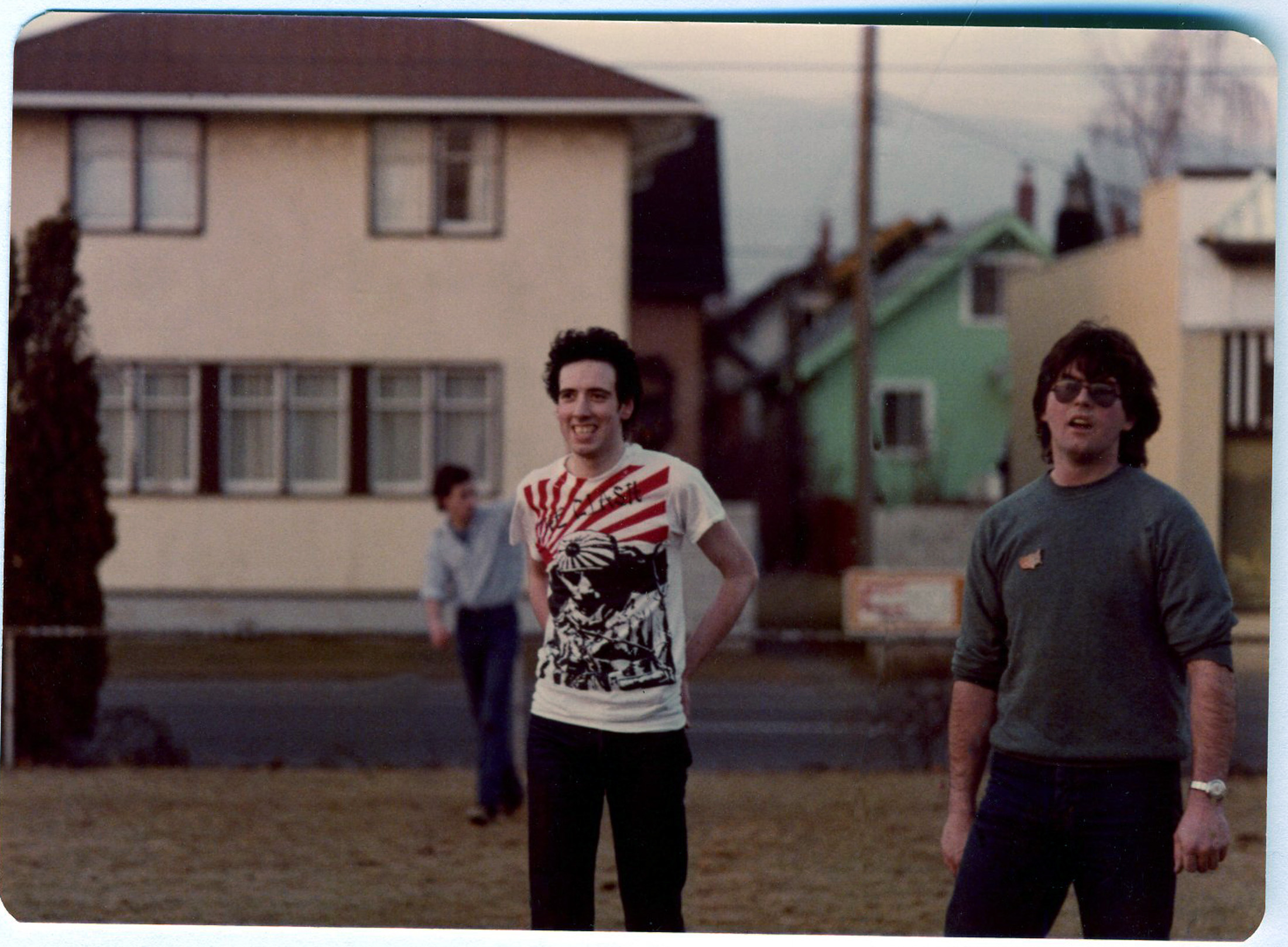

Jones is among the locals who played soccer with the Clash, at McBride Park on 4th Avenue, as he remembers. While a few journalists were on hand—including Tom Harrison, seen in the photo below with Mick Jones—there “was no crowd watching on the side or anything,” Jones recalls. “Literally, there was no one there. Anybody just wandering by that kinda wasn’t really aware of what was going would go, ‘Holy fuck, that’s the Clash playing soccer with a bunch of punks on the field!’”

Journalist Tom Harrison (right), Mick Jones of the Clash (centre), Nick Jones of the Pointed Sticks (background.) Photo by Heather Ewasew.

Jones—who had been to England for parts of 1977 and 1978, and had seen the Clash before—is not quite sure how the game came together. As he recalls, the band had not come prepared, wearing their tour merch as soccer jerseys and their Doc Martens in place of soccer shoes, so it was probably suggested impromptu. “The Clash were staying at the Denman Place Hotel, and I know that Scott Beadle, Jon Doe, Simon Wilde, Sue McGillivray, and a few of the other punks were hanging around.” (A complete, decisive list is not available, but Gerry Hannah of the Subhumans was also in the game, as well as music journalist Eric von Schlippen). Whoever made the suggestion—Corsage front man Phil Smith suggests it might have been Pointed Sticks manager Stephen Macklam—Jones just remembers “all of us thinking, that was a pretty good idea, for us to play soccer against the Clash!”

Phil Smith wasn’t hanging out at the Denman Place at the time, but he heard about the game from the “person-to-person internet of 1979.” As word got out, people got excited. “Everyone knew there was a game, and those who could make it, made it.” Smith played left wing, “to not much avail, I might have to say—I think I got a few good passes in, and that was about it.”

Forty-one years on, memories are not entirely reliable. Heather Ewasew, who went to the game with her friend Susan McGillivray and took the colour photos seen in this story, says the game took place at Trafalgar Park, but far more people say McBride. The afterparty at 509, according to Nick Jones and John Armstrong, was after the Windmill show; but McGillivray and Jon Doe of the Rabid are sure it was after the Clash concert itself. More than one person says Grant McDonagh of Zulu Records played in the game, but Grant himself says he did not.

Ideas vary on who was onstage the night the Clash came to the Windmill. Nick thinks it was probably the Pointed Sticks on the bill with the Rabid, while John Auber Armstrong—also known as the Modernettes’ Buck Cherry—suggests in his first memoir, Guilty of Everything, that it was Active Dog, as he recalls front man Bill Scherk threatening the audience with a squirt gun he’d filled with his pee, with which he promised to douse people if they gobbed on him.

Jon Doe of the Rabid—who definitely did play the Windmill that night—remembers the gig well.

“Made me pretty nervous, to be honest,” he says. “I was about 16, and it was a big deal that the Clash were in town.” At one point, in the “aggressive style the band was known for,” Doe spun around, “and my guitar cord pulled down the massive stack of Marshall and Fender amps I was playing through.” Afterwards, Strummer was asked to draw his impression of Vancouver for local fanzine Snot Rag. “And it was a drawing of me,” says Doe, “with my amps cascading down behind me. Funny!”

The Rabid at the Smilin’ Buddha, 1980 (left to right, Simon Wilde, Sid Sick, Jon Doe). Photo by Bev Davies.

The soccer game took place after the Windmill, Doe says with certainty, “because I spoke to Joe at the soccer match, and he told me I was a ‘really good player.’ I thought he meant soccer, but he corrected me and said ‘guitarist.’”

That the Commodore concert happened after the soccer game is clear—or maybe it was the same night. Nick Jones was at the show, and says the floor was beyond packed. “I can guarantee you that was the fullest the Commodore ever was. Estimates are probably from 1,300 to 1,500 people in there that night. The Clash were letting people in the back stairs. There were people who went in at soundcheck and hid in their dressing rooms with them, with their blessing. It was insane how full it really was.”

One of those let in the back way was Jon Doe. He’d bought a ticket—which he could barely afford—but was underage, and was refused entry. “I sent word to Joe via the band’s DJ”—Barry “Scratchy” Myers—“that I needed help getting in. Fifteen minutes later, he arrived at the door and told me to follow him. We went into the back alley behind the club, and he got me in and gave me a backstage pass. I got to watch the whole show from side-stage. As Joe walked onto stage, he had on these ultra-cool blue brothel creeper shoes, and I commented that I really liked his shoes.”

Afterwards, the band, including Give ’Em Enough Rope producer Sandy Pearlman, was en route back to the Denman Place Inn for a pit stop. Strummer asked Doe to help Sandy get there. As Doe recalls it, the band was on the way to 509 by taxi, and Doe and McDonagh waited in the lobby to join the entourage. “As Joe came down the stairs, he had a brown paper bag in his hands. He threw it into my lap and said, ‘This is for you.’ I opened the bag up, and inside were Joe’s cool blue suede brothel creepers. What a great guy.”

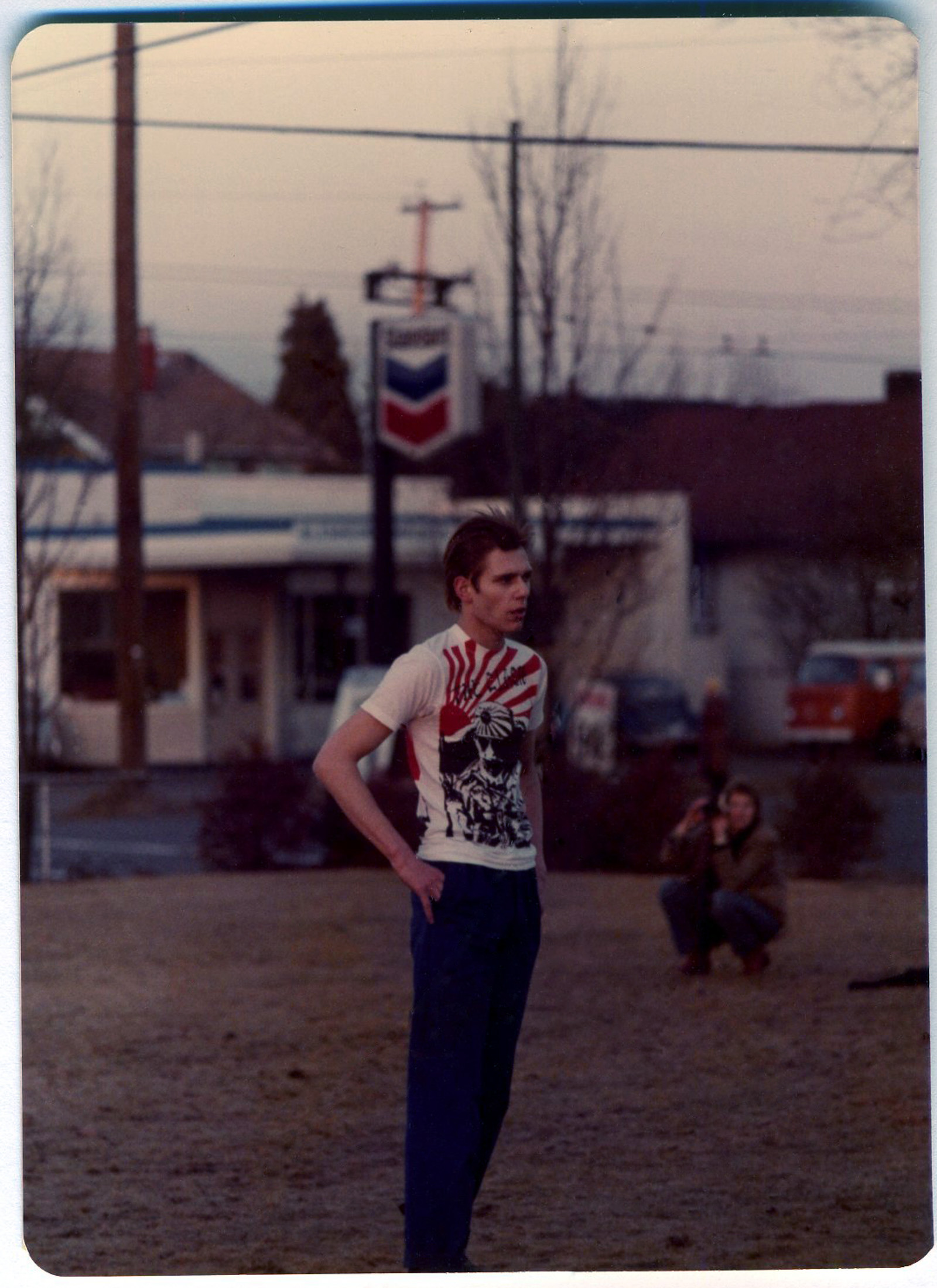

Susan McGillivray—a.k.a. Sue Short of the Devices and, later on, the second lineup of the Dishrags—was also part of the processional to and from the Denman Place where, she says, “Topper let me read his diaries and gave me a Pearl Harbor ’79 tour t-shirt”—the same shirt you see Simonon and Jones wearing in Ewasew’s photographs—“and had all the band sign it. It was my treasured possession, but an ex-boyfriend fancied it too, so I never saw it after we broke up. People thought I was a slut for going back to the hotel, but to be perfectly honest I was just a kid, age 17, and not at all interested in trying to do the Clash.”

McGillivray was also at the afterparty, where drugs had been broken out. Suddenly, “the cops walked in the front door.” She told Topper to collect the band, “as I knew the sneaky way out through the bathroom to the alley outside 509 Cordova. I was just a Swiss-army-knife girl who could sneak around unnoticed and get out of sticky situations by knowing the back alleys and places to hide.”

McGillivray describes the episode as, “How Susan prevented the Clash from being fucking arrested,” and says she wears the badge with honour. “No one I know could have done it as they were too busy snorffling drugs and booze!”

She insists the afterparty was after the Clash show, because she vividly remembers trying to convince Devices bassist Kim Henriksen to come with her. McGillivray describes it by email from her new home in Australia: “It was definitely the afterparty of the gig, because Kim went home and MISSED IT!!! I will never forget Kim getting on the 20 bus up Granville to go home and me and Solly”—Soledad Reeve, who organized the 509 party—“trying to beg her to stay out. She was a moody 14-year-old then.”

Tom Harrison’s impression of the whole visit was that “there was a real strong feeling among the band of trying to bond with the local punk rockers.” But as amicable as relations between the Clash and Vancouver punks were, people were less nice on the soccer field. For instance, Clash road manager Johnny Green was charming to the girls off the field, but—according to Nick Jones—was “a big monster, playing as though his life depended on it” during the game itself. Similarly, Phil Smith describes bassist Paul Simonon as “a real shitkicker,” out for blood—an impression Jon Doe seconds, word-for-word: “He had his Doc Martens on, and made a point of kicking the shit out of your shins if you had the ball!”

Clash bassist Paul Simonon, at McBride Park. Photo by Heather Ewasew.

By contrast, John Armstrong says Simonon, when not playing soccer, “was nothing like you’d think he was. He looks like such a hard man, in all the pictures, this tall aloof brute, and he was, like, the funniest, goofiest guy.” (Simanon has also become an accomplished painter, by the by.)

Mick Jones, too, was “just a sweetheart,” Armstrong recalls. The night of the party, Armstrong and Jones drank together and talked Keith Richards and the New York Dolls and Mott the Hoople. “We all loved the same stuff, grew up on it,” so it was an almost immediate bond. “Punk rock was like that. You would go to another place, and you didn’t know anything about the people or where you were or the culture, and you’d meet someone who loved the New York Dolls, and bang, you were just pals.”

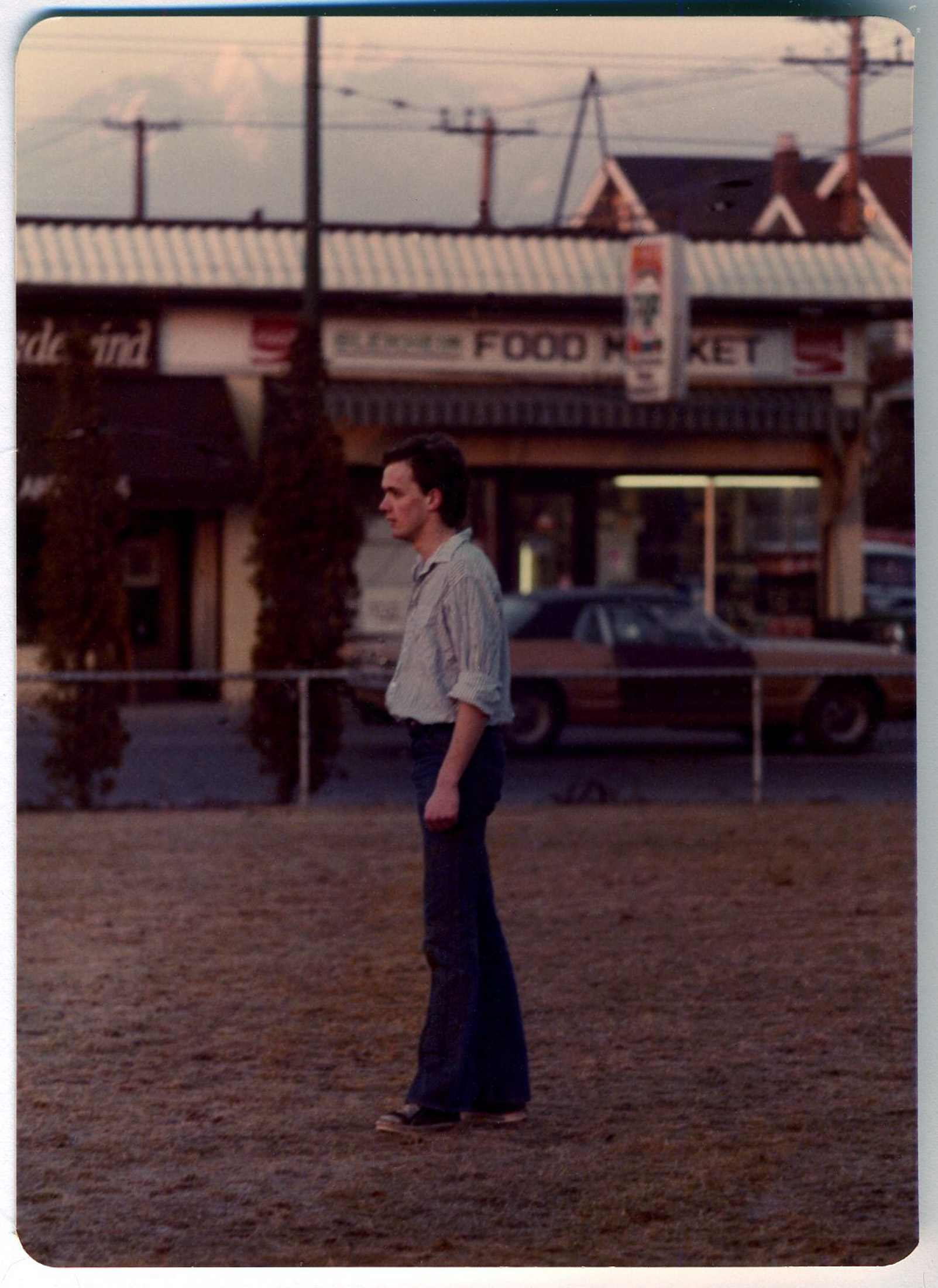

But Nick Jones and Mick Jones had a very different experience of each other at McBride Park, where Nick Jones recalls shin-hacking the guitarist. “He went down, and he came up screamin’ and cursin’ and making like he was going to come for me. He didn’t, but he was doing a bit of English-style swearing and intimidation. I wasn’t worried about it or anything like that, but after that, we decided that discretion was the better part of valour, and I went in goal, and probably allowed the last two goals of the game.” (But not on purpose: “They clearly had more skill and experience than us,” Jones clarifies.)

“They beat us, by the way—some people say we won that game, but we didn’t. We lost 5-3, that I can remember.”

Pointed Sticks front man Nick Jones. Photo by Heather Ewasew.

Tom Harrison puts the loss in perspective. “For a lot of us, like me, our soccer education probably came from recesses at school. So we kind of surprised ourselves—we actually scored a few goals, and we were playing guys who actually grew up playing football—uh, soccer. And we did fairly well! I guess they could have killed us, they could have really turned it on.” He thinks the fact they didn’t was evidence of “a real kind of simpatico between what Vancouver was trying to do with their own punk rock scene, and what they were doing.”

Many other signs showed the Clash were sincere and good-hearted, not the least of which was inviting one of punk’s first all-girl bands, the Dishrags, to open, along with Bo Diddley.

Dishrags leader Jade Blade—a.k.a Jill Bain—recalls, “We got on the bill because the Clash’s manager at the time, Caroline Coon, was booking all-female opening acts—a gesture that made us really appreciate the Clash and their politics.” The Clash would later ask the Dishrags to open for them at the Paramount in Seattle.

The Dishrags were also impressed that the Clash had come to the Windmill gig the previous night. “To us they were such punk megaheroes, so it really impressed us that they would be interested and humble enough to want to come check out a local show. I don’t remember anything about the soccer game, but that they participated in this would seem to say the same thing. The other evidence of their friendliness and enthusiasm was that the band came and danced at the side of the stage when we played ‘London’s Burning’”—a well-known tune off the Clash’s first album—“as our encore. It was such a thrill to look over and see that happening, and having them dedicate ‘London’s Burning’ to the Dishrags in their own set was also one of those moments we will never forget!”

The original Dishrags (left to right, Dale Powers, Carmen “Scout” Michaud and Jade Blade.) Photo by Bev Davies.

Fast-forward a few years, and the original three Dishrags would end up performing in a Supremes cover band called the Raisinettes, who would then change their name to the Raison D’Etres to become backup vocalists for Phil Smith and Corsage, even appearing in the video for “The Shame I Feel.”

Fittingly, Corsage would open for the Clash the very last time they played Vancouver, at the Pacific Coliseum in May 1984, after Mick Jones and drummer Topper Headon had both been fired from the band.

The Clash had been to Vancouver a few times between, including a more discordant appearance in October 1979, when DOA opened for them (a story Joe Keithley recounts in his memoir, I, Shithead). And of course, by 1984, they’d had radio hits like “Train in Vain,” “Rock the Casbah,” and “Should I Stay or Should I Go.” But Phil Smith remembers that Joe Strummer wasn’t all that different when they crossed paths that night in 1984.

“I seem to remember when we came in, Joe Strummer sort of recognized Jade”—who was singing backup vocals along with Scout and Dale Powers of the original Dishrags—and said, ‘Oh, the Dishrags, you playin’ with us again?”

“And Jade said, ‘No, we’re part of another band,’ and Joe said, ‘How many in the band?’ And Jade said, ‘10,’ because it was, like, the big-band thing, and he said, ‘Oh, yeah, well, you guys need a proper sound check. Take as long as you like.’ They gave us full catering and afterparty. It was a different Clash, but talking to Strummer just briefly, it didn’t seem any different.”

The Clash’s soccer game at McBride Park isn’t mentioned in much writing about the band’s first North American concert but, besides winning respect among the locals, the game started another unremarked local tradition. Vancouver punks, for a while anyway, formed a team on the local scene, to play, as Jon Doe tells it, “almost every UK band that came to town, along with most Jamaican bands too. Soccer is like music; it’s a universal language.”

We’re sure Joe Strummer would agree.

Read more tales of Hidden Vancouver.