Jackboots march down Granville Street. A mob of soldiers with swastika armbands storm the CBC Radio studio in the Hotel Vancouver. At city hall, the mayor is captured, a clerk assaulted, and the treasurer forced at gunpoint to open the seven-ton door to the vault. An order is read declaring the city under Nazi occupation, with the elected mayor and council to be immediately replaced by a gauleiter named Erich von Neurenberg.

A special edition of the Vancouver News-Herald hits city streets with the banner headline, “New Order for B.C.” The newspaper is renamed the Neueste Nachrichten (Latest News) and carries a photo of the mayor’s wife kissing him before he is hauled off to a concentration camp.

At the intersection of Georgia and Granville Street, armed men in grey uniforms with bucket helmets halt a streetcar and direct traffic. Later, a procession of storm troopers goose-steps past the Hudson’s Bay store. An aged man and woman, ropes tied around their necks, trail behind like animals on a leash.

A man offers guttural commands in German. He receives an enthusiastic “sieg heil!” in return, the uniformed men stretching out right arms in a salute familiar from the newsreels of the day. Automobiles screech to a halt and horns honk. A lunchtime crowd gathers to gawk. Others go about their shopping with hardly a glance at the commotion.

Sinclair Lewis had warned about a fascist takeover in his 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here. But on February 25, 1942, as the Nazis occupied most of Western Europe, it did happen in Vancouver.

Happily, it was a publicity stunt.

The local Junior Board of Trade, a collection of civic-minded young businessmen, bankers, and other future civic leaders, conjured up “Streng Verboten” (Strictly Forbidden) Day to bring home to their fellow citizens the terrors of tyranny to be faced if the war in Europe was lost. The elaborate dramatization and simulation of a Nazi occupation was intended to bring the war home—and to promote the sale of war bonds.

Men in Nazi costumes salute a man wearing an iron cross as part of Streng Verboten Day war-bond drive, February 25, 1942. Photo by Jack Lindsay/City of Vancouver Archives.

Other civic groups took up the cause. The Kiwanis club marked the day by replacing its weekly luncheon with a slice of black bread and a small bit of sausage to show the deprivations of life under the Nazi yoke. To make the same point, a chain of local bakeries displayed small loaves of black bread alongside beautiful brown Canadian loaves.

Local merchants joined in by placing advertisements in the city’s daily newspapers. “Hitler says it is ‘Streng Verboten’ to sell jewellery. Come in and inspect our selection,” noted jewellers O.B. Allan. “We defy Hitler!” declared B.M. Clarke, which sold women’s undergarments at four city locations, “and offer you the finest selection of hosiery… lingerie… and corsetry in Vancouver.”

Mock Nazis were on the march in other cities, too. In Windsor, Ontario, whose neighbour across the Detroit River had only been at war for a few months, faux Nazi agents at city hall slipped on swastika armbands as fifth columnists to aid in the capture of the building by uniformed raiders. At the end of the exercise, the city’s acting mayor, Arthur Mason, ordered all the armbands rounded up and burned.

“We’re not going to have any of those around the city,” Mason said.

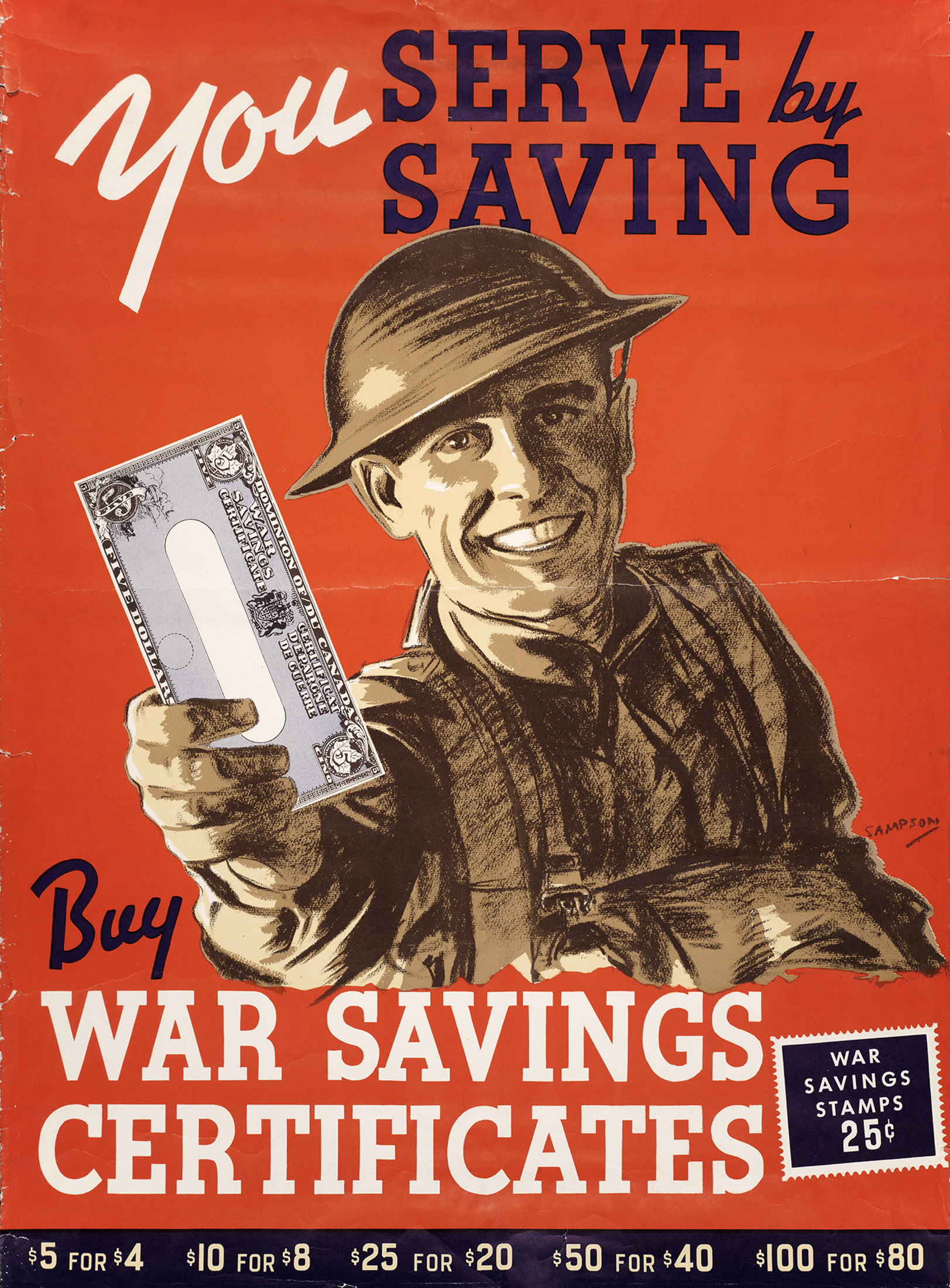

A poster urges Canadians to buy war bonds, 1939. By Joseph Sampson/Toronto Reference Library.

In Winnipeg, a week earlier, the Royal Canadian Air Force flew over the city in warplanes painted in German Luftwaffe livery. Some 3,500 Canadian Army soldiers deliberately failed to defend the city against men supplied with German soldiers’ costumes ordered from Hollywood. The invaders used borrowed armoured troop carriers from the army to blockade bridges before seizing the mayor, premier John Bracken, seven of his ministers, the lieutenant-governor, and the visiting Norwegian ambassador to Washington, who were escorted under armed guard to Lower Fort Garry. On the fort’s grounds, the Union Jack was lowered, replaced by a swastika flag.

The pretend Nazis harassed civilians at every opportunity, chasing them from streetcars and pushing them off sidewalks. At coffee shops, customers paying their cheques received useless paper Reichsmarks as their change. Churches were shuttered. Books were tossed into a bonfire burning in front of the library. In the cafeteria of the Great West Life Assurance company, storm troopers evicted workers before sitting down to enjoy the meals left behind. One officer made a crude pass at a waitress, roughly grabbing her arm. A newsboy selling copies of the Winnipeg Free Press had his copies seized by rampaging soldiers, who roughed him up for selling unauthorized materials.

The events were called If Day, as in “If the Nazis Win Day,” a demonstration of life under Nazi occupation, where proclamations ordering “death for disobedience” were posted in public places.

Over in war-torn Britain, the day’s drama was depicted in a 90-second British Pathé newsreel screened before feature films.

Life Magazine published 22 photographs over a three-page spread in the edition dated March 9, 1942, under the heading, “Winnipeg is ‘conquered.’”

Back in Vancouver, the day’s shenanigans concluded when the occupiers invaded a luncheon. They were forced to flee by men wearing masks of the wartime Allied leaders, Winston Churchill, Franklin Roosevelt, and Joseph Stalin. The man in the unpleasant role of portraying the German führer was Charles Elkin, a local who had been born in Germany.

The phony invaders did not escape unscathed. Canadian soldiers marching to barracks pelted the Nazis with tomatoes outside the Hotel Vancouver.

After three weeks, the war-bond drive was declared a success. Under the guidance of businessman J. Lyman Trumbull, a tea and coffee importer, the city sold more than $31-million in war bonds, about $3-million more than its quota. The war lasted another 41 months.

Read more tales of Hidden Vancouver.