Not much is known about Annie Sachs.

She was born in Cleveland to a mechanic and his wife in the summer of 1891. She married a German immigrant named Jacob Sachs in Portland, Oregon. (The marriage licence recorded she was over 18, though she was only 17.) She had two daughters before the young family moved to Vancouver, where her husband worked as a supervisor at the Imperial Rice Milling Co. warehouse on Railway Street. A third daughter was born in the city late in 1915, by which time the family lived in a house at 1176 Burrard Street, near Davie Street, just down the block and across the street from St. Paul’s Hospital. They later moved to Kitsilano.

Annie Sachs would not live to see her youngest daughter’s third birthday.

On October 5, 1918, the first case of Spanish influenza was diagnosed in Vancouver. Three days later, Sachs was dead, likely the city’s first victim. By New Year’s Eve, 618 were dead.

Many of the dead were between the ages of 20 and 40. There were reports of people who had left for work in good health being sent to the morgue by nightfall.

Before the disease ran its course, almost one in three residents of Vancouver were sickened by the virus. More than 900 Vancouver residents died in three waves of sickness. Across the province, some 4,000 people died.

The Spanish flu washed over British Columbia like a tidal wave.

Staff at Vancouver General Hospital prepare a bed, 1919. Photo by Stuart Thomson/City of Vancouver Archives.

To read contemporary newspaper accounts is to follow a growing daily death toll, as doctors and public health experts scrambled to treat the disease and to limit its spread. Surprisingly, many of the articles were published on inside pages, as though highlighting the news might reflect poorly on the city’s reputation for commerce and hygiene.

But the city was in crisis. With the war overseas leading to a shortage of trained nurses, young, unmarried women were pressed into service with as little as 30 minutes of training. Many of them paid a terrible price. King Edward High School was emptied of students for use as an emergency hospital.

In 1976, Dr. Harry Milburn, who was 90, described for the Vancouver Sun a scene he would never forget at the school.

“I remember the big rooms with those windows way up high and the rows of cots, and the nurses, white-attired with white masks, tending them,” he recalled. “They looked like ghosts walking through a graveyard.”

Outside the city, in Coquitlam, the virus raged through an emergency military hospital for soldiers who arrived by train.

Early news reports of Spanish flu in 1918 would be eerily echoed a century later by the initial coverage of the COVID-19 pandemic: the disease was a problem elsewhere; only travellers to the province were succumbing to the disease; only a mild version was present. The horror was someone else’s problem—until it wasn’t.

“Every case in Vancouver at the present time can be traced direct to contact with travellers from outside points,” Mayor Robert H.O. Gale said early in the pandemic. He assured the citizenry the epidemic did not have the “malignant character” responsible for so many deaths elsewhere. He attributed the good fortune to the city’s climate.

The flu ward at Vancouver General Hospital. Photo by Stuart Thompson/Vancouver Public Library collections.

In Victoria, the city’s medical health officer urged residents to keep their windows open. “The best disinfectant is plenty of fresh air, and all the sunlight obtainable,” Dr. A.G. Price said. “At night keep the windows open and use sufficient bedclothing to keep warm. Eat good food, including a fair amount of meat, sugar and other force-producing matter. Wash the mouth and nostrils with saltwater, as it is very necessary to keep the nostrils clear and the throat clean.”

Cinemas and other public places remained open. Owners assured patrons that premises were undergoing a nightly fumigation.

The earliest reports of death cited two people, a Mr. Peach and a Mrs. Sachs. She was actually the first to have died, two days earlier, on Oct. 8. Anna Clara (née Williams), known as Annie, was believed to have visited relatives in Portland shortly before falling sick. Dr. C. Wesley Prowd certified the Spanish flu as the cause of her death. More ominously, it was reported her husband and the three girls—Freda, 9; Myrtle, 6; Dorothy, 2—were also sick.

Annie Sachs, likely the first victim of the Spanish flu in Vancouver, with husband Fred Jacobs and daughter Freda, circa 1910. Image from Findagrave.com.

At St. Paul’s Hospital, a man identified in the newspapers as Harry Peach (or Pench, or Peuch) died on the morning of Thursday, October 10. Drs. J.H. Hogie and F.X. Phillips certified the death was caused by pneumonia resulting from Spanish influenza. He left a wife and a seven-month-old son. Born in Odessa, Russia, Haim (Harry) Pinchever (also rendered as Pincheff, Pinchev, and Penchévre) had been a butcher and a driver. He had relatives in Seattle and perhaps had been infected there. He was 25.

More troubling was the death of a young man whose name did not appear at all in the newspapers. He had arrived in Port Coquitlam aboard a troop train carrying soldiers for the Siberian Expeditionary Force, destined to sail across the Pacific to do battle against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. When Spanish flu was diagnosed, the troops were placed in quarantine and tents were pitched on the Agricultural Grounds, while Aggie Hall was converted for use as a temporary military hospital.

At 5 a.m. on that ominous Thursday, George Augustus Johns, a strapping young Englishman at 5 foot 11 and 180 pounds, with brown hair, blue eyes, and a ruddy complexion, died from Spanish flu. He was a private in the Canadian Army Service Corps. Born in the Northamptonshire village of Bozeat, the teamster enlisted at Saint John, N.B., about 14 months before falling sick. In his will, completed shortly after enlistment, he left all his possessions, meagre though they must have been, to his sister in England.

Dozens more soldiers billeted in the Lower Mainland would die in the coming months from pneumonia, the Spanish flu, and other diseases.

The deaths were reported in the Friday newspapers on October 11. Of the three major broadsheets, only the Vancouver Daily World put the news on the front page. The Vancouver Sun ran its story on Page 3. The Daily Province slipped a report onto Page 27 under the headline “Epidemic not yet a menace.” The article noted that since none of the city’s 70 cases involved schoolchildren, schools would stay open. The city would be slow to close public venues for fear of harming business.

Vancouver chief medical officer Dr. Frederick Underhill, whose five sons all served during the Great War, two dying in the Battle of the Somme, said he expected only a mild form of the Spanish flu to be seen in the city.

Even after the schools and cinemas were closed, large crowds gathered outdoors to raise money for the war effort. Harry Gardiner, a building-climbing daredevil known as the Human Fly, attracted a crowd of as many as 8,000 to witness his attempt to climb the exterior of the 17-storey beaux arts World Building (now known as the Sun Tower, 128 West Pender Street). Other large crowds gathered to celebrate premature rumours of an armistice.

Most of the flu deaths happened in late 1918 as a mutation of the virus cut a swath of destruction among otherwise healthy Canadian civilians. Many of the dead were between the ages of 20 and 40. There were reports of people who had left for work in good health being sent to the morgue by nightfall.

The Spanish flu got its name in the English-speaking world after the Spanish monarch, King Alfonso XIII, became sick in May. The news was reported around the world. Many assumed the disease had started in the Iberian Peninsula. It did not. Spain was neutral during the First World War, so it did not censor newspaper reports of the sickness. The first known case was reported in March at a military base in Kansas. The virus is believed to have crossed the ocean by troopship to Europe, where it mutated into a more deadly form before returning to North America as troops returned home.

A pandemic had been traced from the battlefields of Europe through Germany and Switzerland before making the leap across the Atlantic, brought by infected soldiers returning from the battlefront. The spread could be traced by newspaper articles as the disease moved from east to west starting in Halifax and then striking Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, and Calgary.

For the record, the Spanish called the ailment the French flu, because they believed it originated with their war-torn neighbour. Some Allied nations described it as the “Kaiser’s Grippe.”

Some deaths in British Columbia were suicides attributed to “the delirium of influenza.”

Arthur Earl Chandler, a Victoria resident and a former councillor in rural Saanich, had been sentenced to a term at Oakalla Prison Farm for carrying banned religious texts distributed by precursors to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. The flu ran rampant through the prison, as more than 40 inmates became sick in a few weeks. In late October, Chandler was said to have suffered a delirium and to have thrown himself backward off a mezzanine balcony onto a concrete floor. The prisoner suffered a fractured skull and died later in Vancouver General Hospital. His body was returned to his home in Victoria for burial in Ross Bay Cemetery. The Victoria newspapers described only an accident with no mention of the suicide, the conviction, or the prison.

BC Archives/Royal BC Museum.

On the same day Chandler died, 39-year-old Malcolm Island logger Gustavus Finnala waited until his wife and 15-year-old daughter were asleep before taking his rifle and shooting himself in the right leg between his hip and knee. His widow later told a coroner’s inquiry her husband had been suffering from the Spanish flu for a week.

The disease attacked rich and poor alike throughout the province

A prominent influenza casualty was John Patrick Murphy, 53, of Lac La Hache, who was the eldest brother of a justice of the Supreme Court of B.C. The cattleman was director of the Enterprise Cattle Company, an amalgamation of four ranches and one of the larger businesses in the Cariboo.

On November 7, the Daily Times in Victoria carried a paragraph about the death of Nicholas Zeifires, employed at the Empress Hotel. The 25-year-old Greek immigrant had been brought four days earlier to the Emergency Hospital at 1124 Fort Street, a former private home named Trebatha commissioned by a dental surgeon and built in Second Empire style in 1887. (The house, now used as offices by an architectural firm and others, still stands today.) Zeifires died of influenza and pneumonia. Left unstated by the newspaper, though appearing on the death certificate, was his occupation as a waiter. Unlike today, when the storied hotel has been temporarily shuttered to help stop the spread of COVID-19, the Empress continued operating during the Spanish flu pandemic.

Another group suffering high casualties were nurses, whether formally trained or volunteers pressed into emergency service.

On November 20, the Vancouver Sun published the names of 17 nurses who died, under the headline “Heroines All.” These included the Catholic nuns Sister St. Jacques and Sister Syncletique; Winnipeg-born Ruth Luno, a Sunday school pianist and an elementary school teacher who volunteered at Vancouver General Hospital; Edith Menzie, who had been nursing Indigenous people in Merritt; and Irene Jones, a 19-year-old probationary nurse at St. Paul’s Hospital.

When he fell sick, C.W. Nunley, a 32-year-old tobacconist from Kentucky, hired Agnes Chambers as his private nurse. He died from the flu on October 19. She continued nursing his sick family until she, too, fell ill, dying six days after Nunley.

Out in Port Coquitlam, Marjory Beatrice Moberly, the daughter of Major Guy Moberly, treated the ill at the military hospital until succumbing to the disease herself. She was 23.

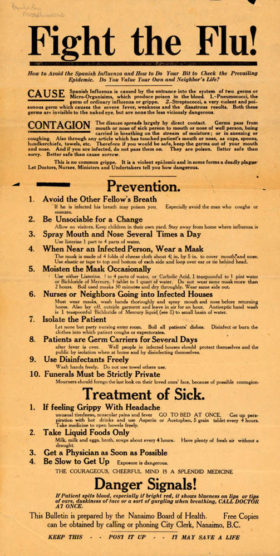

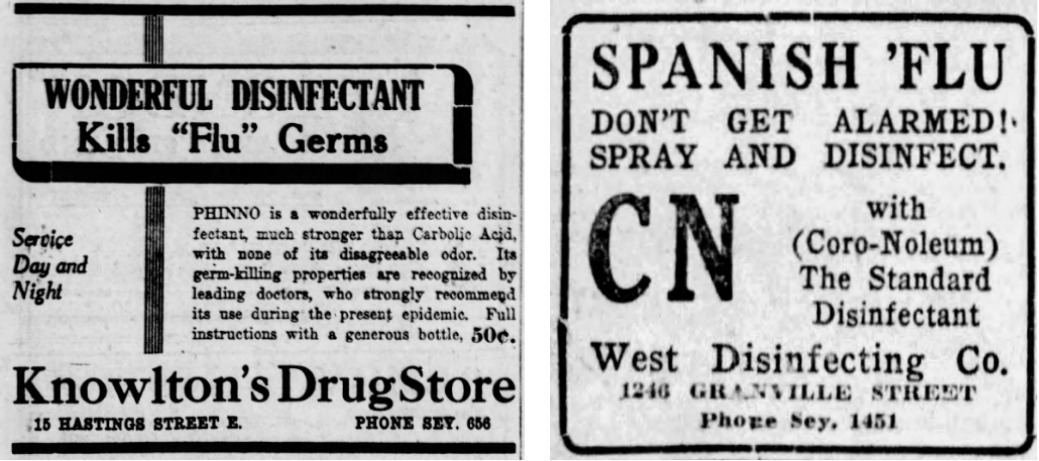

Then, as now, the spread of disease was seen as a business opportunity by some. Drugstores sold remedies like Phinno disinfectant, Reid’s Grip-Fix, and Woodward’s Cinnamon Pyretic Compound. Homemade gauze masks sold for 35 cents. Boot shops urged patrons to buy high-quality footwear lest wet feet bring on the Spanish flu, and rubber manufacturers touted their slip-on products for the same reason.

Advertisements for anti-flu products. Left: Vancouver Daily World, Oct. 26, 1918. Right: Daily Province, Oct. 22, 1918.

There were also quack cures. Francis T. Gook, who usually peddled curative mineral waters, placed a newspaper advertisement offering Gook’s Anti-Grippe Capsules, a concoction to cleanse digestive organs.

Some items were sold in advertisements disguised to look like legitimate newspaper articles. HOW TO AVOID PNEUMONIA WHEN CONVALESCING FROM THE ‘FLU,’ read one headline for Kennedy’s Tonic Port. There were Fruit-a-tives and Dr. Williams’ Pink Pills.

The deadliest first wave of Spanish flu in Vancouver peaked in October 1918, while the final wave crested in late January 1919 with the disease petering out by March.

The loss of life was stark.

Vancouver had a population of about 100,000, meaning 900 deaths would be the equivalent by proportion of 5,000 today (in the city of Vancouver proper, not including the surrounding suburbs). Across the province, 4,000 deaths in 1918-19 would be the equivalent of 37,000 British Columbians dying today, notes Vancouver Coastal Health.

As of April 2, 2020, 31 British Columbians have died from COVID-19.

As suddenly as the Spanish flu virus appeared, it faded, first from the hospital wards, then from public memory.

Once the bodies were buried, the city quickly returned to business as usual. The virus dropped from the public imagination just as quickly as it had arrived. Memorials were not erected to the unfortunate dead, nor to the dedicated doctors and nurses who died while treating the sick.

Sachs (the mother of three), Pinchever (the Russian-born butcher and driver), and Johns (the soldier) were among 55,000 Canadians who died over two years of the pandemic, nearly as many as were lost in four years of war overseas in Europe.

To appreciate the city’s toll, one has to visit Mountain View Cemetery.

In the summer of 2013, Harry Pinchever’s monument in the Jewish section of Mountain View Cemetery was cleaned as part of a restoration project started by Shirley Barnett with the support of the Schara Tzedeck Cemetery Board. Johns is buried in the military section at Mountain View. Nearby, though not with a military gravestone, is the marker for young Marj Moberly, the nursing sister who “died in the executing of her duty.”

The final resting spot for Annie Sachs, the first identifiable victim of the pandemic, is also at Mountain View. Her entire household suffered from the Spanish flu. Happily, her husband and three children survived. Jacob remarried the following August. The three daughters all lived into their nineties.

The youngest, Dorothy Katherine (née Sachs) Simms, died in Sacramento, California, on Christmas Day 2011, two days before what would have been her 96th birthday. She outlived her birth mother by more than nine decades.

Read more tales of Hidden Vancouver.