This story is the 12th in our series on the hidden history of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. Read more.

In their 2014 book Gender Failure, writer and performer Ivan E. Coyote recounts moving from the Yukon at 19 to Vancouver’s West End. It was there they met Rosie, a transgender woman with kitten heels and a voice like “an eighteen-wheeler gearing down.” A bond grew between the two as they made extra cash restoring discarded alleyway antiques, before Rosie disappeared from Coyote’s life. “I still remember everything I learned from Rosie,” Coyote writes. “She taught me how to take something some people might just throw out, and then sweat and work and love it back to beautiful.”

Like the refinished antiques in Coyote’s story, the West End is also a product of loving reinvention, from its origin as the city’s prestige area to its upcycled incarnation as an LGBTQ-friendly launch pad for newcomers drawn by the possibilities of this neighbourhood, as they are to the restaurants, nightlife, and proximity to numerous beaches and Stanley Park.

While the West End (bounded by English Bay to the southwest, Georgia Street to the northeast, the park to the northwest, and Burrard Street to the southeast) was uninhabited forest before the arrival of Europeans, Indigenous settlements existed on the tip of the downtown peninsula, most notably X̱wáýx̱way, a Squamish village with a 3,000-year history. Most accounts tie the area’s recorded history to the arrival of the “Three Greenhorns” in 1862, three Englishmen named Samuel Brighouse, William Hailstone, and John Morton, who were mocked for buying 180 acres each of future West End real estate to exploit for brickmaking. When that enterprise (and others) failed, they donated one-third of the land to the Canadian Pacific Railway.

On the expanse cleared by the CPR, a residential area began to form in the last two decades of the 19th century. By the time the city incorporated in 1886, this part of town housed the city elites and their mansions on Blue Blood Alley around West Georgia Street. The area took its name from the West End school on Burrard Street. In the following decades, businesses developed on Davie, Denman, and Robson Streets. Along English Bay, the beach was patrolled by the city’s first lifeguard, Seraphim “Joe” Fortes, the Trinidad-born (or, depending on the account, Barbados-born) immigrant whom the Vancouver Historical Society, in 1986, named its “citizen of the century” for teaching generations of Vancouver children to swim and saving dozens of lives.

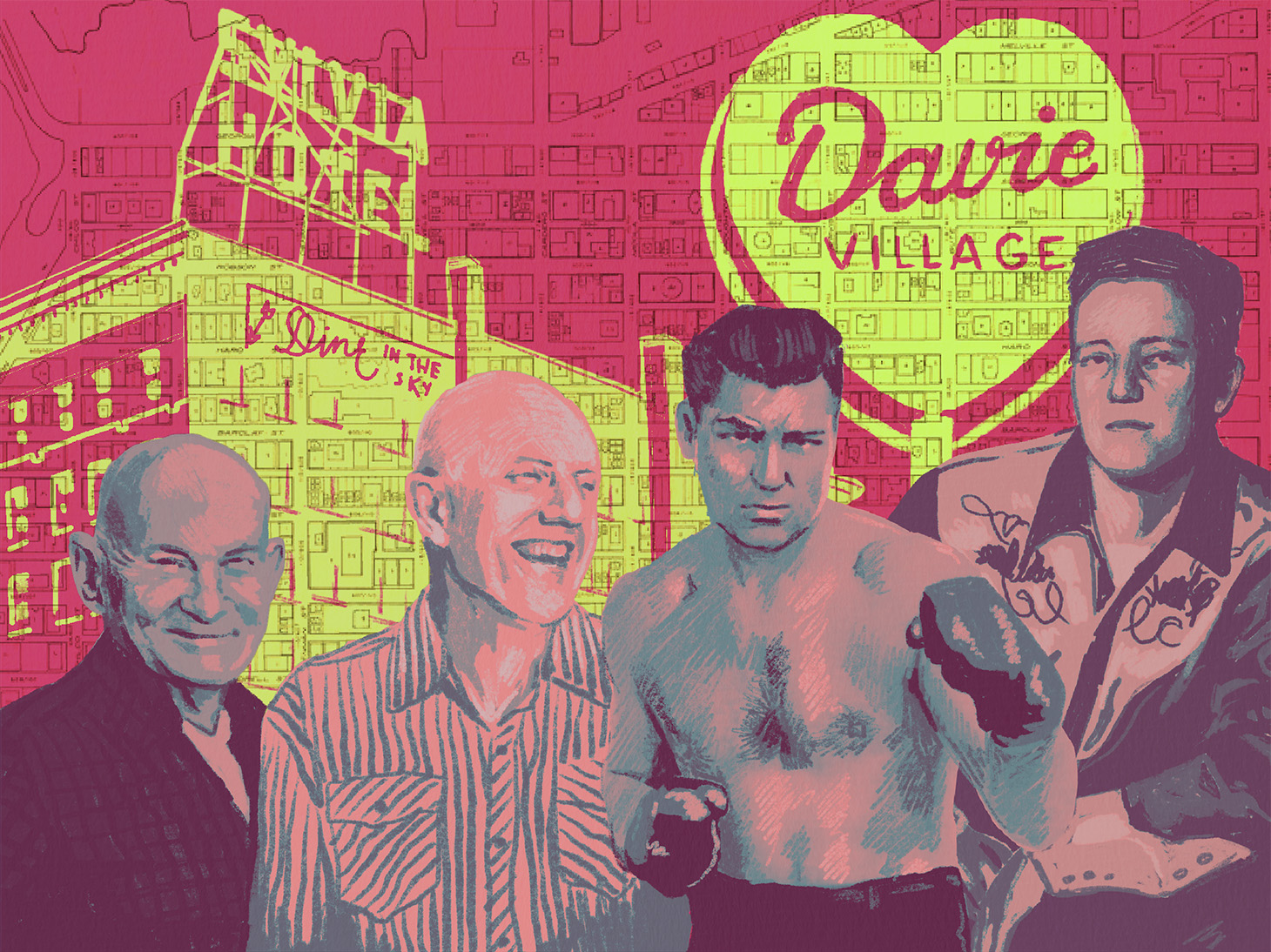

An architectural walk will allow you to see the wraparound porches and gabled roofs of the past that still endure, but you won’t be able to stroll past the Denman Arena. Built in 1911, the 10,500-seat barn hosted the city’s one Stanley Cup-winning hockey team, the Vancouver Millionaires, in 1915, as well as a Jack Dempsey boxing match and a beauty contest judged by Rudolph Valentino, before being demolished after a fire in 1936.

The early decades of the next century saw West End demographics change sharply. As rich folks decamped to Shaughnessy, the area’s Victorian and Edwardian mansions were converted to apartment buildings that accommodated a quickly growing city. Around this time, midrise apartment buildings also began to appear in the area. Opened in 1913, the Sylvia Court Apartments, an eight-storey building overlooking English Bay, was named by owner Abraham Goldstein after his daughter. It became an apartment-hotel in 1936 and at one point converted its top floor into a Dine in the Sky restaurant. In a poem titled after the Boston ivy-covered hotel, George Fetherling notes how:

Vines grow thick and knotted

That squirrels might use them

as a staircase to peek into the

rooms of lovers peeking out.

For decades, the Sylvia stood as the tallest building in the West End. But a highrise-building boom followed the conclusion of the Second World War, including the notoriously view-obliterating Ocean Towers in 1960. The new construction prompted the author of Under the Volcano and West End NIMBY Malcolm Lowry to bemoan in verse:

With clawbars they have gone to work on the poor lovely houses above the sands

At their callous work of eviction that no human law countermands

Meanwhile, a German community began forming on Robson Street, north of Burrard Street. In 1962, Vancouver Sun columnist Allan Fotheringham called Robsonstrasse, as the thoroughfare was known, the most interesting street in the city. “It’s a street of hanging rows of salami, of redolent cheeses, fresh fish, books and records and proud blonde girls from Hamburg and Copenhagen.… It is always alive.” Cultural amnesia being what it is, Robson is now known as the street that once held two Starbucks kitty-corner from each other. It’s also notable for its high-end boutiques and plethora of Korean restaurants and Japanese ramen shops.

As the 1960s progressed from cosmopolitan toward hedonistic, the West End’s nightlife kept pace. At 1022 Davie, a building that started its life as a dance academy and apartment house in 1911 and, from 1940 onwards, was known as the Embassy Ballroom, evolved into a venue for rock music first known as Dante’s Inferno but most fondly remembered as the Retinal Circus. It hosted well-known acts such as Country Joe and the Fish, Velvet Underground, and The Doors. Downstairs, weed comedian and musician Tommy Chong operated a blues club called the Elegant Parlour. In 1982, after many name changes, the venue became the iconic gay club Celebrities.

Although the story that B.C.’s eighth premier Alexander Davie was the province’s first gay politician is likely unfounded, there’s no doubt the street named after him has been a mecca and sanctuary to LGBTQ folks since the 1970s. In 1987, one of this community’s cultural hubs, Little Sister’s Book and Art Emporium, founded by Jim Deva and Bruce Smyth, made a stand against homophobia by taking legal action against Canada Customs for confiscating shipments as obscene, and finally won at the Supreme Court in 2000.

Through the 1970s and into the 1980s, the Davie Village section of the West End also served as the city’s red light district, inhabited by gay and trans people who banded together to keep one another safe from violence and exploitation. “The people on Davie Street have been working on their own for years. We don’t allow pimps down there,” says a sex worker in the 1984 documentary Hookers on Davie. “We make our own money, and we don’t pay anybody for protection. We protect ourselves and each other.”

However, upset by drug activity and clients driving through their neighbourhoods, some residents successfully lobbied and organized to drive the sex workers out of the area. A West End Sex Workers Memorial now stands in front of St. Paul’s Anglican Church, and the traffic-calming barricades are reminders both of this era and of the darker legacy of displacement to the Downtown Eastside.

As it currently stands, the West End is—by far—Vancouver’s most densely populated area. It’s also the most transient, has a higher proportion of households with no children at home, and rapidly growing Latin American and Middle Eastern communities. While many live there, the rest of the city never runs out of reasons to visit, whether it’s for the Pride Parade, a pet-immiserating spectacle that celebrates “light,” or to spark up together. One of the city’s oldest residential areas, the West End still might be its most beloved.

Read more Vancouver Neighbourhood stories.