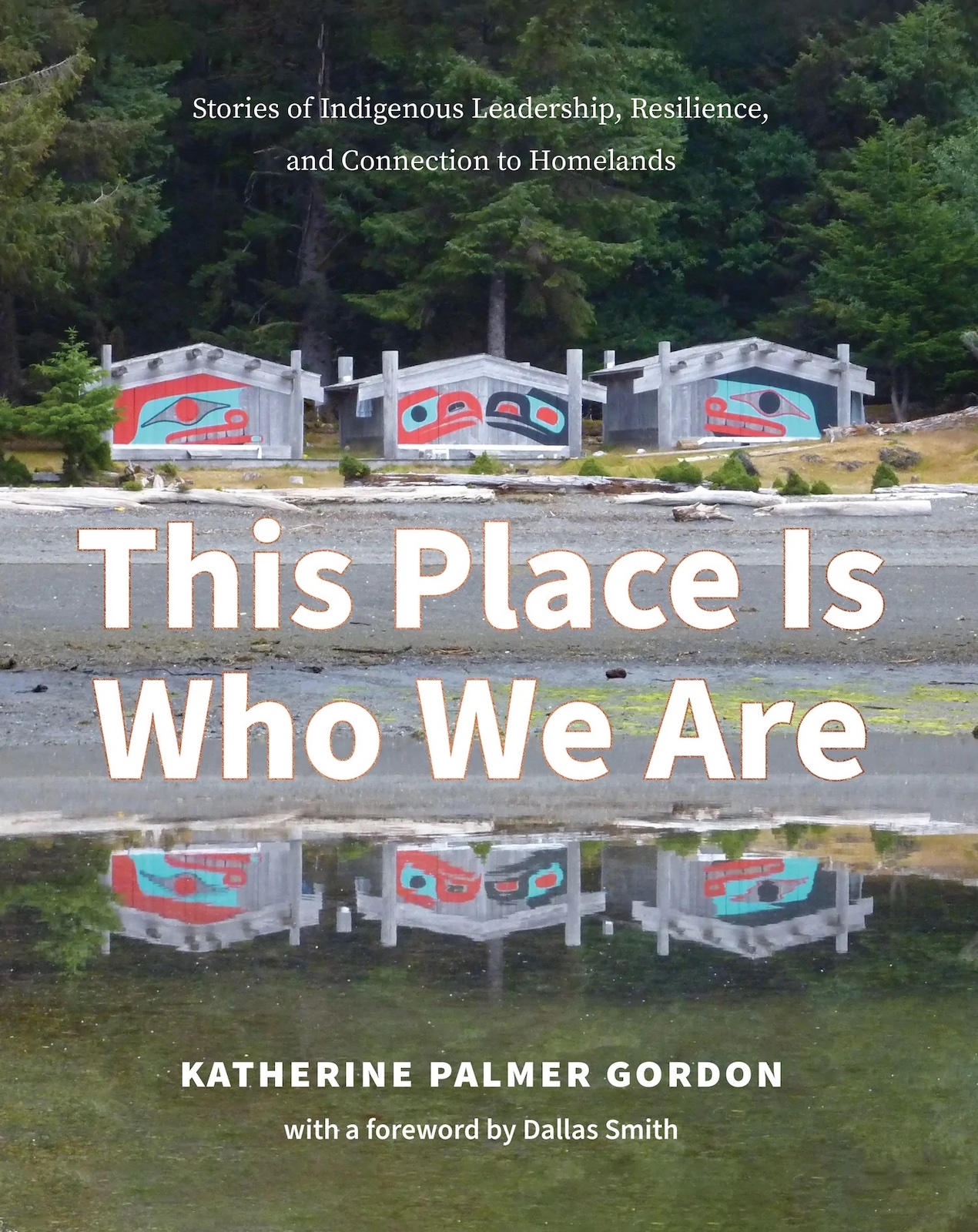

Katherine Palmer Gordon has a long history of working with Indigenous peoples in intergovernmental relations and writing about treaty negotiations, reconciliation, and leadership. This passage is excerpted from her latest book, This Place Is Who We Are: Stories of Indigenous Leadership, Resilience, and Connection to Homelands, which tells 10 inspiring stories about how Indigenous communities in British Columbia are reconnecting to their lands and waters.

“Reconciling who Wei Wai Kum are as Indigenous people requires us to be in tune not only with our physical world, but the supernatural world and related ways of thinking, and our belief that all things are connected. It requires an intergenerational investment in our cultural identity, knowledge and values, and the wellbeing of our lands and our resources. That is our wealth as Ligʷiłdaxʷ people, and I believe that has to be our bottom line.”

—Chief Councillor Christopher Roberts, Wei Wai Kum First Nation, October 2020

The homelands and traditional waters of the Wei Wai Kum First Nation, to which Wei Wai Kum people have ancient physical, spiritual, and cultural connections, span the headwaters of Loughborough Inlet, north of ƛəmataxʷ (Tyee Spit) and the city of Campbell River, and stretch south to the Tsable River, west to the mountains that straddle the centre of Vancouver Island, and east to southern Johnstone Strait in the Salish Sea.

The Wei Wai Kum Campbell River reserve, on which many citizens of the Nation reside (centre right in picture, with red roofs), is surrounded by large-scale commercial and industrial development. Photo by SuavAir Aerial Imaging Ltd.

In the Liq̓ ʷala language of the Wei Wai Kum, who are Ligʷiłdaxʷ people, “Ligʷiłdaxʷ” translates to an “unkillable thing.” It is a reference to a story about a large sea worm that survives and keeps swimming, even when cut into pieces. It is an apt name for a people with a reputation for great strength and survival against difficult, sometimes almost impossible, odds. Christopher Roberts, who was elected as Chief Councillor of Wei Wai Kum in 2018 at the age of thirty-five, is proud of being a citizen of this strong, resilient Ligʷiłdaxʷ Nation and cherishes the heritage and values imbued in that citizenship. The newly elected young Chief had also, however, taken on the leadership of a people confronted by an overwhelming history of colonial assault on their physical, cultural, social, and economic wellbeing; a relentless onslaught that has done much to disconnect them from their homelands, their traditional laws, and sacred age-old community protocols.

In a sad story similar to that of every other coastal First Nation in British Columbia, the Wei Wai Kum had been deemed by the Canadian government of the nineteenth century to be “Indians” under the Indian Act and forced onto a handful of small Indian reserves in and around Campbell River. The government renamed the Nation the “Campbell River Indian Band,” imposing upon them a western-elected governance structure that purported to replace their traditional hereditary leadership framework. Over the course of the following decades, as more and more settlers arrived, the expansive, glorious territory in which Wei Wai Kum people had lived, prospered and exercised self-determination for millennia—a panoply of pristine waters, islands, forests, and mountains—became almost unrecognizable.

Wei Wai Kum Chief Councillor Christopher Roberts at Knight Inlet Lodge. Photo by Brodie Guy.

In 2018, Christopher ran for the leadership of Wei Wai Kum. By then, most of the community lived on a cramped reserve tucked into the waterfront skirts of a city of more than thirty-five thousand residents, in the heart of an industrialized and heavily polluted region saturated with mines, logging companies, and mills. A swath of open-net fish farms littered the Nation’s front doorstep. The Wei Wai Kum had little choice in any of this. For much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Wei Wai Kum citizens were systematically excluded from participation in the industrial resource economy in their territory. At the same time, their cultural livelihood was effectively extinguished as government officials removed or destroyed traditional weirs, traps, nets, and other fishing tools with which they had managed to harvest, consume, and trade with other First Nations in a wide range of sustainable fisheries.

Wei Wai Kum people were also deeply affected by the well-documented crimes of the residential school system, the theft of their children, and unceasing depredations on their culture, language, and traditions. Greatly impoverished economically and socially, their small handful of reserves and federal government program funding were poor substitutes for a once-thriving and environmentally sustainable economy, homelands abundant in thriving resources, healthy, happy, culturally rich people, and independent Nationhood.

Forward Harbour/ƛəx̌əʷəyəm Conservancy, a sheltered bay on the central coast of B.C., lies some 75 kilometres northwest of Campbell River. Photo by Laurie MacBride.

By the time Christopher was elected, it was impossible to turn the clock back on the sprawling commercial and industrial development that had grown around Campbell River. Previous leaders of the Nation, going as far back as Christopher’s great-grandfather William Roberts, had nonetheless worked tirelessly to rebuild Wei Wai Kum’s financial and cultural wellbeing within their present-day setting. The First Nation had become an integral part of the modern Campbell River economy. They owned a number of thriving businesses on their lands downtown, held several forestry tenures, and operated a busy marina on the waterfront. The revenues derived from those commercial activities enabled the Nation to develop environmental stewardship and research programs, partner with the federal and provincial government in marine and terrestrial planning initiatives, expand its database of archaeological sites, and, not least of all, deliver various social and cultural programs to its citizens, as well as undertake language revitalization efforts.

All the same, some stark realities still faced Christopher in his new role. “Nothing could have prepared me for how challenging it is to sit in this seat,” he recalls. Those challenges felt almost insurmountable at the beginning. “I started with this optimistic vision of a future in which we weave together community, cultural, environmental, and economic wellbeing, and we are working toward it, but almost straight away it was really hard to imagine it being achievable. Would it be possible to bring things back into balance, to a way that is consistent with our cultural identity of who we are as a community, as a people? The challenge for us is how we strike that balance of a strong cultural identity rooted in all those values that set us apart without it being all about commerce and being successful economically. Every Nation has this dilemma, but I think that being in such an intense urban setting adds another dynamic altogether.”

It is also a dilemma that has to be negotiated with the utmost care for what Wei Wai Kum citizens, many of them still healing from the brutal impacts of colonization, might expect. Christopher is emphatic that the community must lead the direction Wei Wai Kum takes on his watch. However, like any small community, people are divided on what they want for the future. Do you lead the Nation further down the pathway of commercial development, with all the revenues that come with it, or invest in high-cost social housing and cultural space? If you are offered land that was once stolen from you to purchase at market price, do you accept and pay just to get it back? Do you cooperate with government to garner better environmental standards in the territory, even if they aren’t as high as yours, to at least make some progress? These are the very real daily challenges that confront a young Chief Councillor desperate to improve the lives of Wei Wai Kum people.

Excerpted with permission from This Place Is Who We Are: Stories of Indigenous Leadership, Resilience, and Connection to Homelands by Katherine Palmer Gordon, published by Harbour Publishing, 2023. Read other stories about community.