My late father, Larry MacInnis, didn’t have too many “brush with celebrity” stories. Once, he unintentionally heckled the Everly Brothers (which didn’t end particularly well), and then there was the time that busty blonde starlet Jayne Mansfield brushed into him.

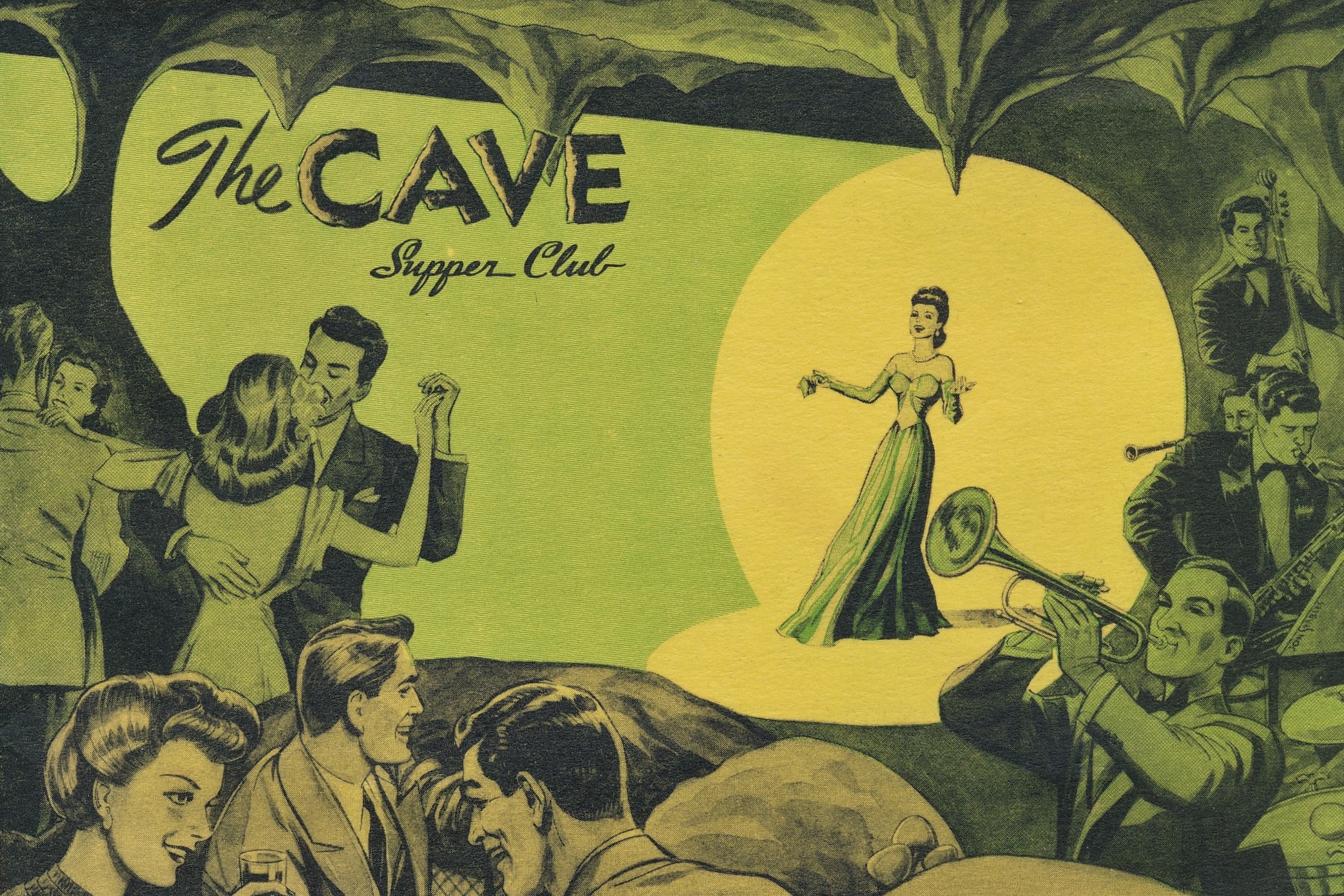

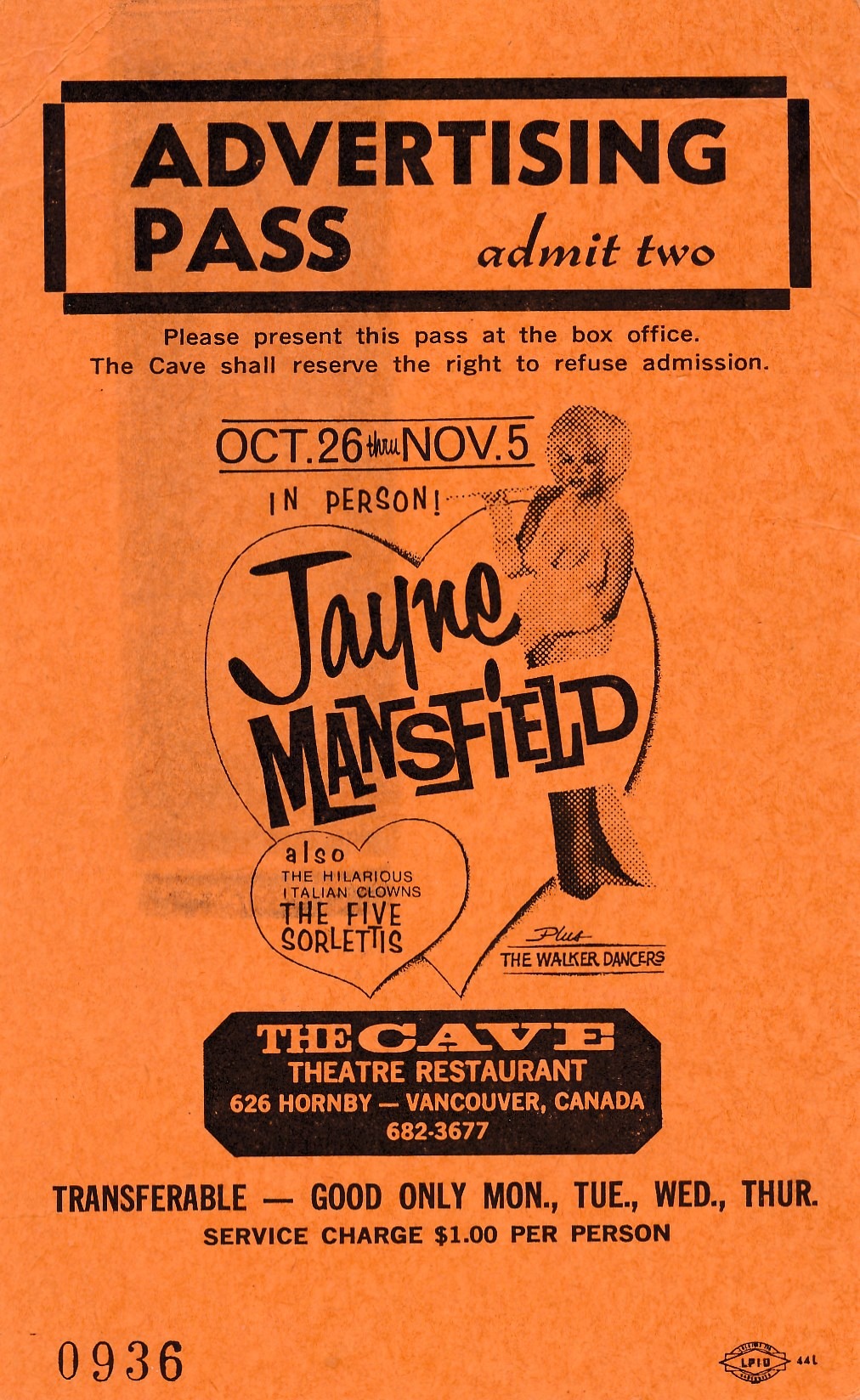

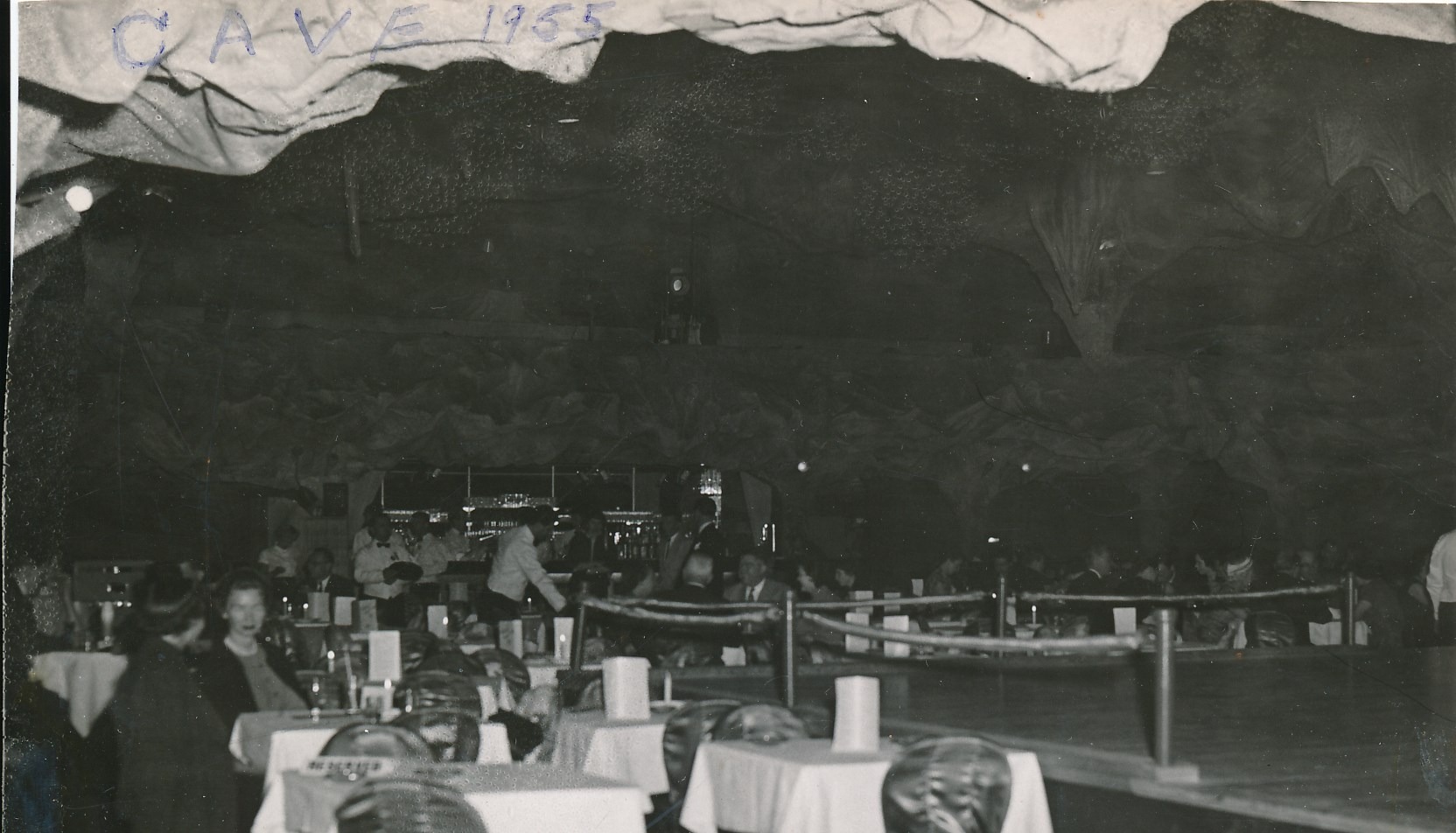

My dad was at the door of what I assume was the Cave Supper Club, the Hornby Street nightclub with stone-like walls and fake stalactites that was a staple of the Vancouver music scene from 1937 until its closure in 1981. Mansfield performed there for a week in late October–early November 1966.

My father is not around for me to ask him to check the details, but I vividly remember him talking about Mansfield while tucking me in one night. He likened her to Marilyn Monroe, and said that it wasn’t long after he’d encountered her that she died in a car accident. As I remember, that’s where I learned the word “decapitated.” (It is apparently not true that Mansfield lost her head in the accident, but that was the word used in newspapers, and my father ran with it).

It’s a weird thing to have in common with someone, but that’s how Anthony Walker (a.k.a. Tony Balony) learned the word decapitated, too—also from his dad, also in regard to Jayne Mansfield—though Walker’s father got considerably closer to Mansfield that mine did, sharing a stage with her when he opened for her during her Cave run.

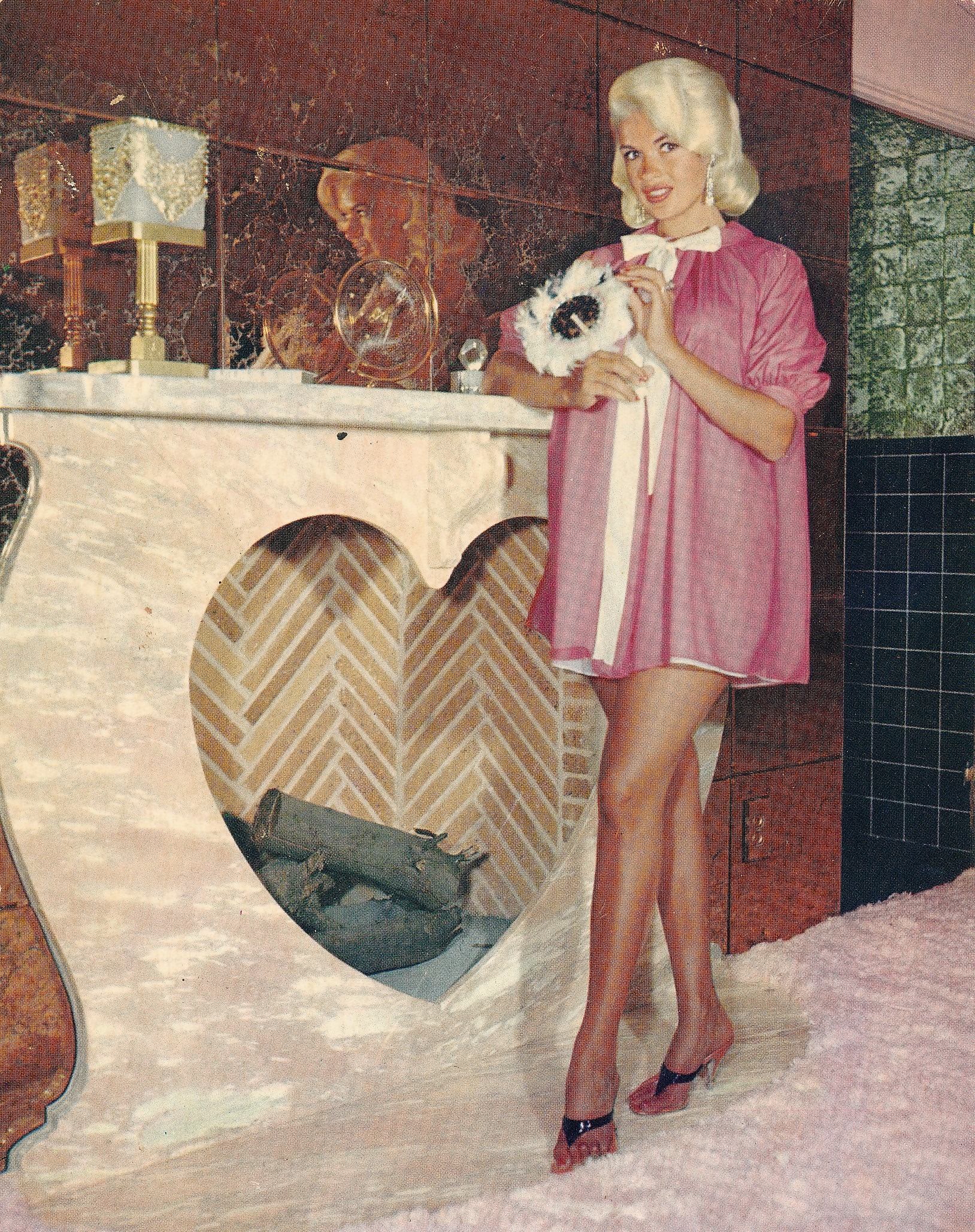

Jayne Mansfield, in a clipping from a 1960 Life Magazine photoshoot by Allan Grant, courtesy of Rob Frith.

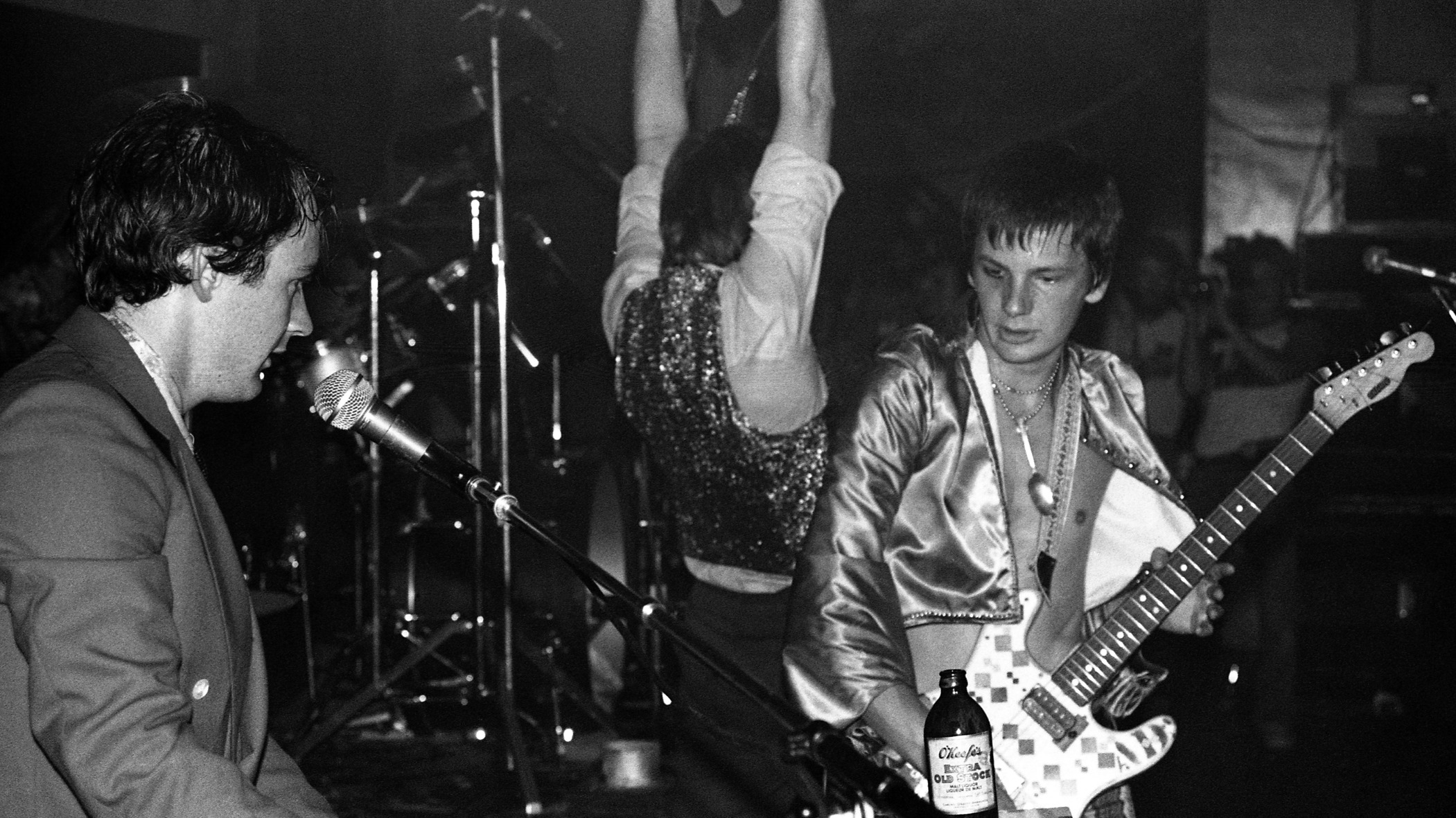

Walker is a Vancouver guitarist with a long and storied resumé, including tenure with the Antheads, the Melody Pimps, the Actionauts, and Kraftdinner, a Kraftwerk spoof band that topped UBC’s campus radio station CiTR with its version of “Trans Europe Express.” Later on, Walker played with Art Bergmann and the Real McKenzies.

Tony Walker with the Melody Pimps at Budstock, July 25, 1981. Photo by Bev Davies.

A love of ballet brought Walker’s parents, George and Audrey, together in the 1950s, and they would eventually open the Russian-American Ballet School in North Vancouver. “My Dad—I don’t want to speak ill, but he was no Rudolf Nureyev, you know,” Walker recalls. “He was one of the grunts who would pick up the girl. My mom was more of the soloist, the prima ballerina, the one who was schooled by Georgie Balanchine.”

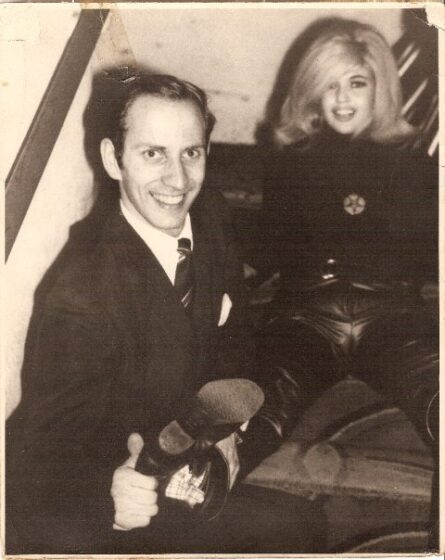

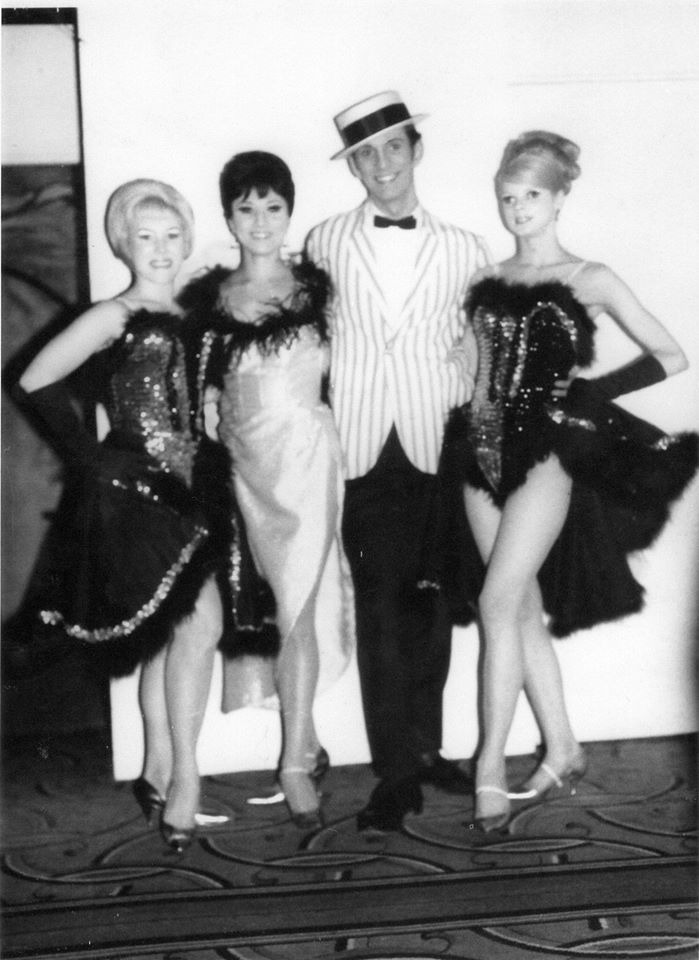

George Walker with Jayne Mansfield, courtesy of Tony Walker.

Dance was not George Walker’s only talent, however. “My dad had always been a great singer. In the ’60s, my dad would work jobs doing his song-and-dance routine at the Cave, with the George Walker Dancers. Sometimes it would be some sort of jazz dancing routine, where they would put on music and dance to a current hit of the time, or he would sing a song. He had one of those straw hats with the cane, and that was his routine. He was really good. I wish I had recordings of him.”

What songs were in his father’s repertoire? “God. I have to think about that. It’s the kind of thing—it’s like trying to remember somebody’s name when they’re standing right in front of you. When I’m around the house, I’ll be singing them to torture my own kids, the same way he used to do to us. Like, whenever there was a topical event, he would just start singing something, like, we’re going to a party and he’ll be singing ‘The Party’s Over.’ He had one of those big boomy Robert Goulet–type voices,” Walker tells me. “As for his setlist, I’m guessing he was probably doing ‘Strangers in the Night’ or something like that. And he was a Motown guy—I wouldn’t be surprised if he was at the Supremes when they were at the Cave.”

George Walker with the George Walker Dancers, courtesy of Tony Walker.

Though he was too young to watch his father’s performances—and never went to the Cave as an adult—occasionally, when he was a boy, Walker would accompany his dad to the club when it wasn’t open. Sometimes memorable things transpired: “He was looking after me one afternoon, and he was doing sound check over there. I had a little colouring book—this was when those goofy trolls that had the hair that stuck up were popular, back in 1966. I was all into them, and I was colouring trolls, and I remember a mike stand onstage like the one that the Four Tops and the Temptations used to have, with a single stand going up and four mikes that came off of it. I would have been five or six, so it’s hard to remember…

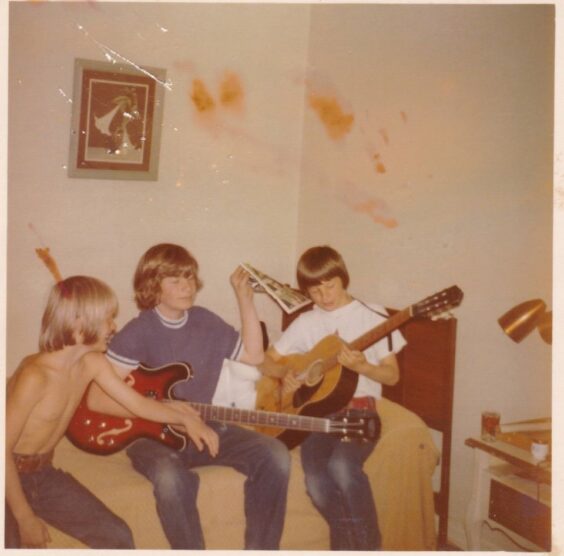

The Walker Brothers, a.k.a. the North Van Mafia: “Vince Walker on the left, Nick with the bass, and myself.” Photo by Audrey Walker, courtesy of Tony Walker.

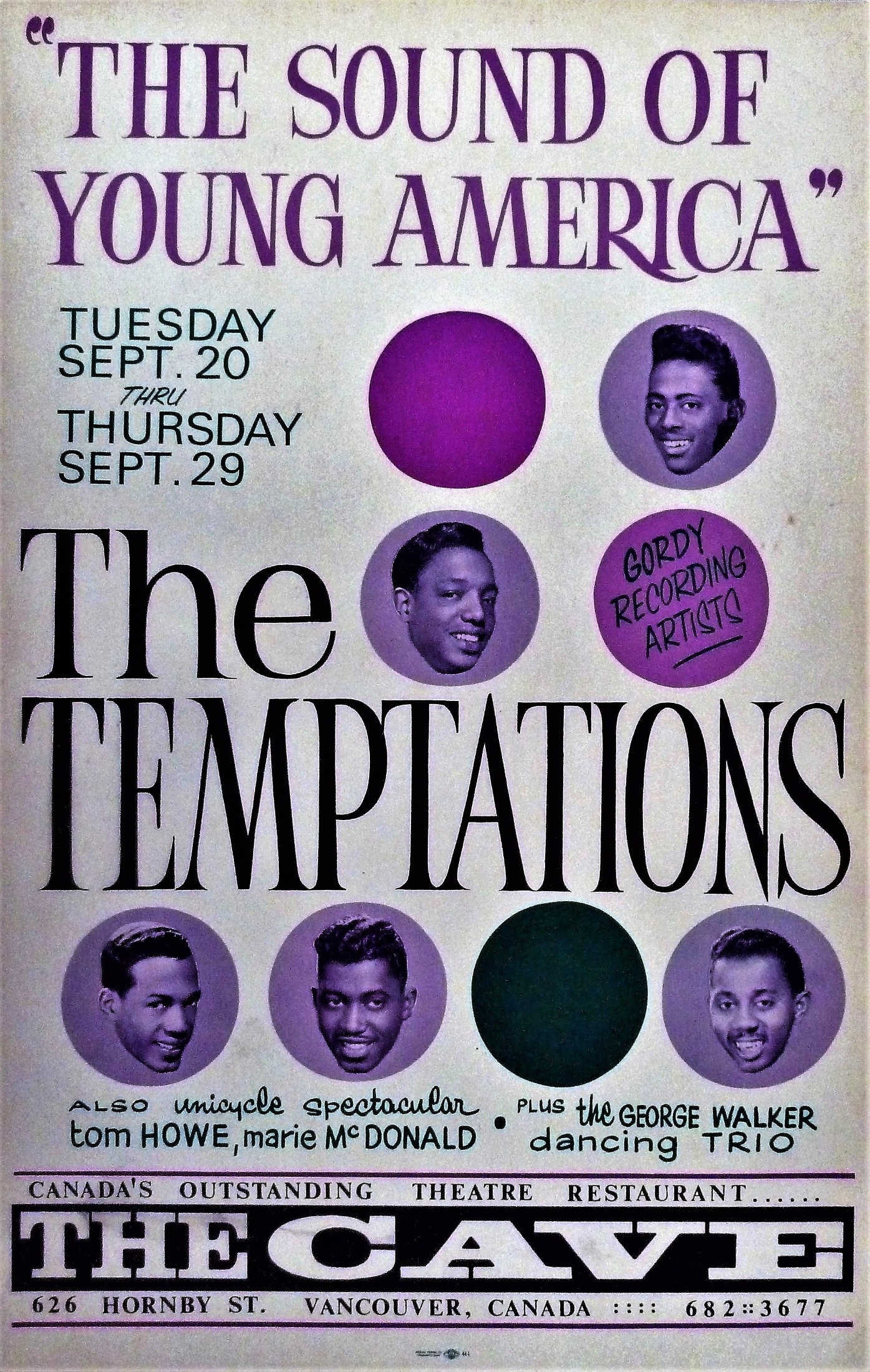

“Anyway, I’m sitting colouring my colouring book, over by the back by the door when you first go in, and my dad comes over and he’s ecstatic. ‘It’s the Temptations, it’s the Temptations!’ Of course, I’d never even heard that word before. All I knew is that there were these four black guys—or five of them?—and I’d never seen a black guy before. And they’re coming over, being really nice—‘Hey, little boy, how you doin’’ kinda thing—and I just remember sticking my hand out, going ‘Lemme see that!’ at his hair, because he had a fuzzy Afro. And he’s going, ‘Yeah, feel that fuzzy hair!’ and I’m scrunching it with my fingers. It was kind of cool, because—I didn’t know at the time, I had no idea—but it was when the civil rights movement was happening. And I remember him holding out his hand and going, ‘See, I’m black on this side,’ and then he flips his hand over, ‘but I’m white on this side, because I’m the same as you on the inside.’ I think about it more now that he said that than I did at the time—because why would I think we were different on the inside? Kids don’t know racism. I just knew that these were black guys with fuzzy hair and they looked pretty cool! And I didn’t have an idea who the Temptations were or what the word meant: ‘What are you talking about, temptations?’”

The Temptations gig poster, provided by Rob Frith.

Walker laughs. “It’s like when Jayne Mansfield died. Dad must have just picked up the paper, and I remember him being just, like, flabbergasted, and he wouldn’t stop saying the word: ‘She was decapitated! She was decapitated!’ It was another word I’d never heard before. ‘Who was decapitated?’ ‘Jayne Mansfield! Her car slammed into the back of a truck!’ Such were the times, that he was describing such a grisly death to his kids.”

Jayne Mansfield guest pass, courtesy of Rob Frith.

Walker senior revealed a bit more of “the Jayne story” to Tony shortly before he died, saying, “‘She asked if I wanted to show her around the town in her Cadillac. I declined since I was married to your mother and had you kids at home.’ I couldn’t believe it. He didn’t make up stories, and the lameness of not getting into a limo with Jayne Mansfield was totally him, so I’m sure that’s true.”

As for meeting the Temptations, and getting a beginner’s lesson in anti-racism, young Anthony soon learned a little more. “I remember later that year, being down in Oregon—my dad’s family’s from Portland—and my grandfather was taking me to his mattress factory, and we drove by this building, and it had all these cool cut-out psychedelic silhouettes of people on the sides of the building. I remember going, ‘Hey, what’s that building over there, Grandpa?’ ‘Oh, that’s the coloured swimming pool. That’s where the coloured people swim.’ And with my dumb little brain, I went, ‘Coloured people? Let’s go, I want to see them!’ Because I’m imagining purple and blue and green, you know? Coloured people. ‘Don’t worry, when we get to the factory, you’ll meet Dallas, he’s coloured…’ And then when we get there, I was let down: ‘Oh, jeez, he’s a black guy! I already met the Temptations…’ I thought I was going to meet a purple person!”

Bev Davies on Tina Turner, Ronnie Hawkins, and “that stupid heart”

Bev Davies at a Gore Street party house, 1979. Image courtesy of Bev Davies.

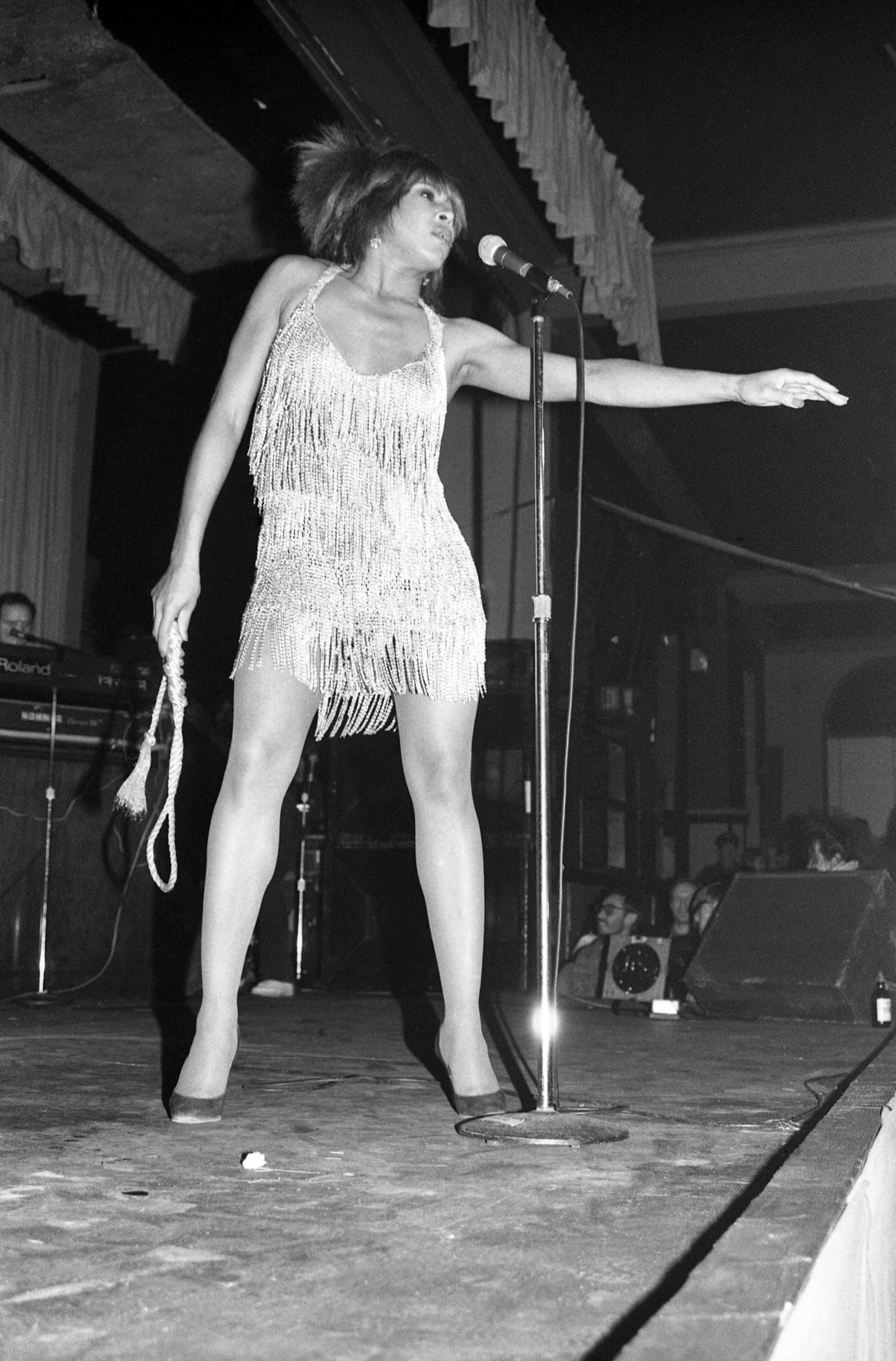

The first show Vancouver punk photographer Bev Davies ever saw at the Cave, a few years after she moved here from Toronto to study art, was Ike and Tina Turner, circa 1972.

The Cave, Davies remembers, had a high ceiling and papier mâché stalactites, which looked pretty hokey to her, since she’d actually gone spelunking with her parents on a trip to the Black Hills of South Dakota and seen real stalactites.

Still, Tina Turner was one of her favourite entertainers, whose records featured prominently in her roommates’ communal record collection.

Ike Turner, she recalls, “was like Bruce [Palmer], the bassist from the Buffalo Springfield: he stood by the amplifier with his back to the audience.” It was Tina who carried the show, and who Davies had gone to see. “One of the things that I noticed about Tina was that she used to be able to do this thing, and I saw it at the Cave, where she would tilt the microphone stand way over, almost to the floor, with her foot, and then bring it back up when she was ready to sing! It was really, really amazing, it was like, Oh God, she has total control over this.”

Tina Turner at the Commodore, 1982. Photo by Bev Davies.

To Davies’ disappointment, the last time she saw Turner, at the Coliseum in 1993, “she had a headset on,” and she no longer did the trick. But in 1972, the exuberance of Turner’s performance floored Davies and her friends. “It took five minutes for us to get them back onstage for an encore—five minutes of yelling and screaming and stomping our feet, and they finally came out. Evidently they didn’t do encores!”

The Cave Supper Club ceiling and decor. Image courtesy of Rob Frith.

Later on, it would come out that Ike Turner was a controlling, abusive figure who beat Tina frequently and badly (she wrote an article about her marriage for the Daily Mail in 2018). But after the couple split, as Davies has heard the story, it was Tina who was rejected by the music industry. “Drew [Burns], who ran the Commodore, had said that the record company had gone with Ike. This is what Drew told me—I have no idea if it really is true—but no one wanted Tina to show up anywhere to do a concert. But Drew and Tina were friends, so he booked her for two nights at the Commodore, and it sold out both nights.”

By that point, Davies had heard about Ike’s abusiveness and noticed, besides the absence of the dancers the Ikettes, a telling physical signifier that Tina had put her relationship with Ike behind her, which is visible in the photographs Davies took. “If you look around her neck, she doesn’t have the diamond heart necklace that she had to wear, because Ike made her wear it. It was shaped like a heart, and it was open in the centre, and there were diamonds around the outside of the heart. I was very supportive of the fact that she’d gotten out of that relationship and wasn’t wearing that stupid heart around her neck any more. I remember standing in the audience going, ‘Great, she doesn’t have it on.’”

The year before those Commodore shows, Davies had gone back to the Cave to see Ronnie Hawkins. She forgets the exact date, but says it must have been somewhere between D.O.A.’s famed Hardcore ’81 showcase (on Valentine’s Day of that year) and when she accompanied D.O.A. to London that September as the band’s photographer. (How did she narrow down the date? Her Ronnie Hawkins images are on her 424th roll of film, while Hardcore ’81 is circa No. 329, and the London shows take up a few rolls in the early 500s.)

Ronnie Hawkins outside the Cave, 1981. Photo by Bev Davies.

“I like Ronnie Hawkins,” Davies says. “It’s a Toronto thing—he’s from the Deep South, but really early on, he moved to Toronto and ran a nightclub right down at Dundas and Yonge Street, right by the record stores. The Coq d’Or was the bar, and the Hawk’s Nest, for teenagers, was upstairs. His band was the band the Band, that went on to play with Bob Dylan” (though they were known as the Hawks when Hawkins played with them, and lacked Robbie Robertson).

According to Davies, the Ronnie Hawkins “story that no one really talks about,” which she heard from her friend Jeanine Hollingshead, “was that when the Band was going out on tour with Bob Dylan, and they were in Toronto, Bob Dylan got in a motorcycle accident and ended up at Ronnie Hawkins’ cottage north of Toronto, recovering for months and months.” Hawkins would later perform with the Band in The Last Waltz and be cast in Dylan’s film Renaldo and Clara as a performer named “Bob Dylan.”

Davies’ other story about Hawkins involves her friend Tannis Neiman, who, along with Hollingshead, took a rather famed 1966 hearse ride with Neil Young to California, where Young and Bruce Palmer hoped to find fame. It was a ride that Davies herself had been invited on, then frozen out of; but, thinking she was going, she participated in the mass pawning of stuff to get money together for the road trip.

“Tannis had a 12-string guitar—not a very good one; she was a folk guitarist. Folk blues, she called it. And she said, ‘Let’s go down to Ronnie Hawkins’ place, I want to see if he’ll loan me $50 for this guitar, and I’ll pay him back when I get back from California.’ So she talked to Ronnie—we sat in his club in the daytime—and he said, ‘Okay, I’ll do it, and then when you get back and you get on your feet, you come give the $50 to me and I’ll give you the guitar.’ And then maybe a year later, she went down there—I didn’t go down the second time with her—and she had the $50, and he said, ‘I’m not giving you back that guitar! Johnny Cash played it and said, “For fifty dollars, it’s not a bad guitar!” It’s proudly on my wall.’ So he wouldn’t sell it back to her.”

Was Neiman disappointed? “No, it was funny, it was great—I mean, she didn’t want the guitar back, she just didn’t want to lose a friend over not paying him back the money.”

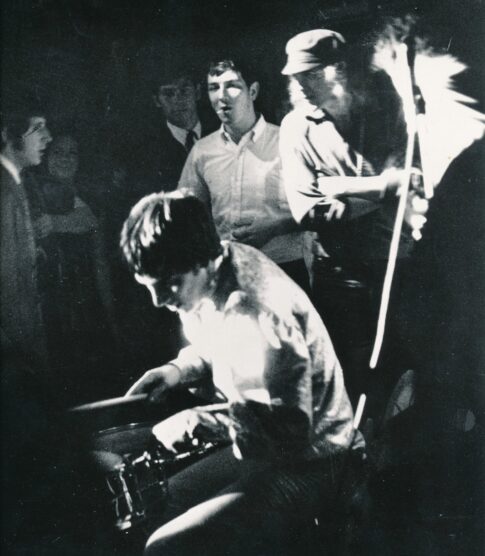

The Who’s Keith Moon gives the Painted Ship’s drum kit a thrashing while Don Xaliman watches, probably on acid

John Entwistle, far left; Keith Moon on drums; William Hay of the Painted Ship, in the hat. Photo by Joyce and/or Bonnie, friends of William Hay, courtesy of Rob Frith.

While Bev Davies had shared a house with members of the Painted Ship, across from Vancouver’s Douglas Park, she never did get to see them play live, and she certainly wasn’t at the famed 1967 engagement at the Cave that saw some very special guests join them on the stage.

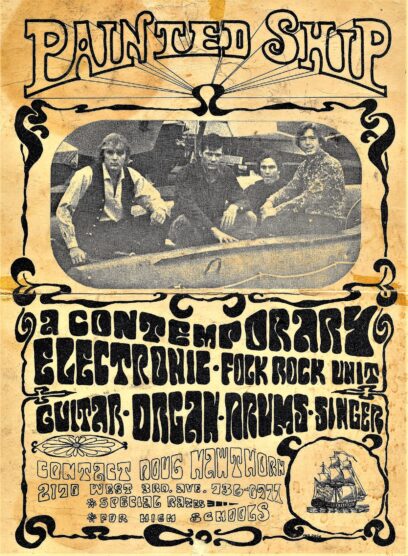

The Painted Ship—who, like the Collectors, were later chosen as one of the bands to represent Vancouver’s 1960s rock scene at the Museum of Vancouver—were named from a line in Samuel Coleridge Taylor’s “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” and are best remembered for three songs, “And She Said Yes,” “Little White Lies,” and “Frustration,” which have appeared on various compilations, including both the Pebbles and Gravel series, and Neptoon’s The History of Vancouver Rock and Roll Volume 3. There’s also a weirder, less anthologized A-side, Audience Reflections (from Polyana’s Dreamworld).

Painted Ship vocalist William Hay, who authored or co-authored all four of those songs, explains the context of the Cave gig. He had “purposely kept a month free—no touring. No Vancouver gigs. I’d written several new songs and wanted to introduce them to the boys. Two days into this plan, our manager phoned me and said that the Cave wanted to book us for a week. Apparently the Vegas act they had booked couldn’t make it. I said no, I wanted to work on the new songs, and there were a couple of problems with the Cave for me: first, until this time, the Cave booked Vegas acts—Sammy Davis Jr., Mitzi Gaynor, et cetera, so they had an expensive cover charge. Secondly, they tended to be aggressive with liquor sales. I didn’t want our fans to deal with either of the above so I told our manager no. The next day, our manager phoned me again and said that the Cave had agreed to lower the cover charge to next to nothing and not hassle people about drinking. I took the offer to the musicians. They wanted to do it. I still preferred to work on the new material, but I relented.”

This was in July 1967. “The shows went surprisingly well,” Hay remembers. “More folk showed up than the management had expected. Jack Wasserman [a columnist for the Vancouver Sun] came to one of the first nights and gave us a great review. After the first week, the Cave management asked us to do a second week, which we did. The crowds stayed good, and they asked us to do a third week. I said no—time to work on my new songs.”

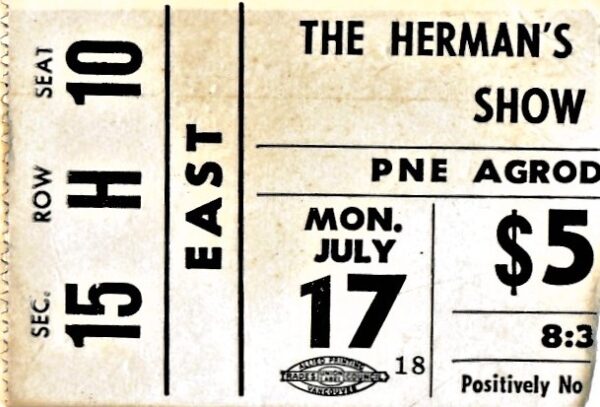

Ticket stub from the Herman’s Hermits show at the Agrodome, courtesy of Rob Frith.

One night into the second week—likely July 18, the night after the Blues Magoos and the Who opened for Herman’s Hermits at the Agrodome—“I go on stage and see that three front row tables have been roped off. A couple of songs into our first set, members of the Who and Herman’s Hermits arrive and occupy these seats. At one point we start a cover of ‘Satisfaction,’ and boys from the Who and Herman’s Hermits come up on stage. Keith [Moon, then 20 years old] gave our drum kit the thrashing that it deserved. Lots of fun. I talked with Keith and John Alec [Entwhistle, the Who’s bassist] after the first set. They were very cool , especially John who went out of his way to recommend me to his favourite English producer.” (More of that story can be read here, a chain of events that, though full of potential, sadly did not result in a Painted Ship LP.)

Was Pete Townshend—the Who’s guitarist and songwriter—even at the gig? It’s unclear, but he probably didn’t take the stage. Richard Evans, the Who’s art director and web manager, says that at the Agrodome show, “Pete smashed his only guitar, thinking he had a replacement. He didn’t. So unless he borrowed one, he wouldn’t have been playing.”

Audience member Don Xaliman remembers the Agrodome show, and was also at the Cave the night in question. Xaliman is best known as one of the core members of another unusual Vancouver group, the Melodic Energy Commission, who in their early days featured Hawkwind’s Del Dettmar on synths. While Dettmar has shifted his focus to other things, most of the key members of the MEC—Xaliman, theremin player George McDonald, dulcimer player Randy Raine-Reusch, and bassist Mark Franklin—still record, having released Electreum: Psychedelic Soundscapes From the Age of Electronics in 2019.

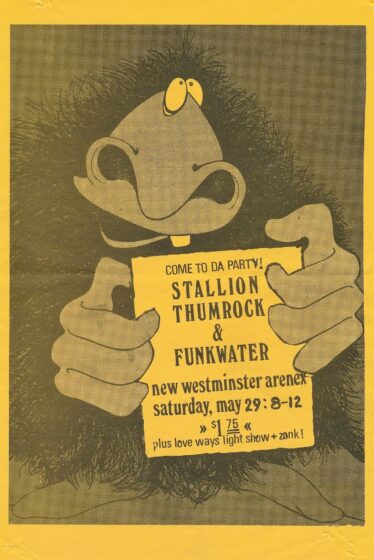

Love Ways Light Show poster, courtesy of Don Xaliman.

However, Xaliman’s presence on the Vancouver music scene dates back much earlier, to the 1960s, where he first gained notice for providing psychedelic light shows at dances and concerts. “It was called Love Ways Light Show, and we worked mostly with Major Gribbits Frog Band and Yellow Brique Rd, and we did teen dances up and down the Fraser Valley. We kept getting hired by Terry David Mulligan and Stevie Grossman—Stevie Wonder, he called himself; he was a DJ.”

He did a light show once at the Retinal Circus, though he doesn’t remember for whom, and he thinks he did a show for the Collectors in Chilliwack, who would later morph into the band called Chilliwack. But Xaliman is not quite sure about that, either: “I think they hired us to go out there, or wanted to hire us, but we did an awful lot of acid and stuff,” he confesses. His giggle is gentle, playful, and slightly naughty. “In fact, the show was basically, we’d fill a wine bottle up with lots of hits of acid and do our light shows while sipping the stuff. That was our weekend, right? Weekend gigs!”

Don Xaliman at an Easter be-in at Lumberman’s Arch in 1968 or 1969. Photo courtesy of Don Xaliman.

Love Ways Light Show had a very hands-on way of making light: “We just got a whole bunch of slide projectors and overhead projectors and oils and liquids, and made slides out of all kinds of things, and little spinning crystals and stuff like that. A totally organic feel—no computers, nothing pre-programmed, nothing planned other than we’d maybe hang a sheet up and try to get the balcony. That was the really nice thing about old light shows; they didn’t pay respect to a rectangular screen. There was no need to stay on the screen—it was an environment. You stick a crystal in front of a slide projector and it shoots light out all over the place. It was like being in the band, and we’d have two or three people running it, and we’d be, like, visual musicians.”

It was around that time that Xaliman ended up in the audience at the Cave. He was 17, still “sporadically attending high school,” and “wasn’t allowed into many clubs. I think the drinking age was 21.” He remembers in particular being turned away from the Afterthought, a key location in Kits for the Vancouver counterculture. He had been introduced to the Who by his “school bud” Martin Webb, who would later write for the New Musical Express. When the Who were added to the Herman’s Hermits bill, Webb and Xaliman were there.

After the concert, “or probably the next day,” Webb dragged Xaliman down to the Biltmore, where the bands were staying. “We were just hanging outside on the sidewalk, looking up at the window, and we got word that some of them were going down to the Cave, so we hopped on a bus and went down there, and managed to get in.”

Painted Ship gig poster, courtesy of Rob Frith.

Xaliman didn’t have a fake ID, he says, but “nobody really asked.” He was well aware of the Painted Ship. “They were totally on the scene, playing different places about town. They would play the courthouse, down outside, and a few other places, like galleries and such. I really liked the Painted Ship, but I didn’t know they were playing there that night.”

Webb went over to talk to the star guests, while Xaliman hung back and listened to the Painted Ship. “And then a bunch of them started playing—I think it was the guitar player from Herman’s Hermits, and Keith Moon, and Peter Noone, from Herman’s Hermits—he was the singer. They did the ‘Satisfaction’ song, but they broke it into letters, like ‘Gloria,’ G-L-O-R-I-A: S-A-T-I-S-F-A-C-T-I-O-N. Which I thought was kind of cool. They didn’t play for very long. I definitely remember sitting there wondering if Keith was going to break all the drums, and I’m sure the drummer from the Painted Ship was feeling about the same way!”

Judith Beeman remembers seeing Roy Orbison and Ray Charles at the Cave in her teens

Judith Beeman. Photo by Patty Sudan, courtesy of Judith Beeman.

Don Xaliman was not the only underage person to get into the Cave. Judith Beeman—music fanatic, record collector, and publisher of Back of a Car fanzine, which was devoted to the music of Big Star and Alex Chilton—caught Roy Orbison and Ray Charles there, both thanks to her mom, back when Beeman too was 17.

“I was with my mom, in January of 1980, when we saw Roy Orbison,” Beeman tells me. “She had been an inside worker at the post office, and somebody she knew had an in with the Cave and would get lots of guest passes. I believe my ticket had been designated for another friend who couldn’t make it, and as the clock ticked down to showtime, I was invited.”

It was a 10-day run of shows, Beeman recalls. She and her mom and her mom’s coworkers arrived after the opener, and the hostess led them to the seats, which were “very decent, facing the front of stage. The place was packed, and I was quite in awe of the venue, knowing its reputation.”

In hindsight, Beeman feels she wasn’t as excited as she should have been about seeing Roy Orbison, but who was Orbison to a 17-year-old in 1980? “My personal musical tastes in my mid-teens hadn’t yet evolved much past FM rock radio,” she admits. “I wish I could remember more. I mostly recall a hushed sense of reverence for the clad-in-black Mr. Orbison. This was pretty much a large comeback for the musician, who had lost his wife and two children in previous years.”

Some months after the Roy Orbison gig, “my mom asked if I wanted two tickets to see Ray Charles. I wound up going with a friend from school. We had both just started Grade 12 and it was a school night. Again, I wasn’t as familiar with, nor as interested in, the artist as I should have been. We arrived embarrassingly early, probably before 9:30, and I doubt there were more than 10 other people in the room. I’m quite sure we looked like children, yet the woman who took us to our seats was extremely polite. It was clear we had arrived with a guest pass, and we were treated nicely. I suspect everyone else in the room was at least three times our age.”

Jack Marsh—a local supporter of the punk scene, who would help promote shows at the Cave—confirms that the nightclub had a pretty liberal policy when it came to alcohol: “The Cave was a popular location for suburban high-schoolers and underage SFU students (mostly young ladies, but a few fellows, also). The running joke was that anyone on the far side of 15 could get a drink.”

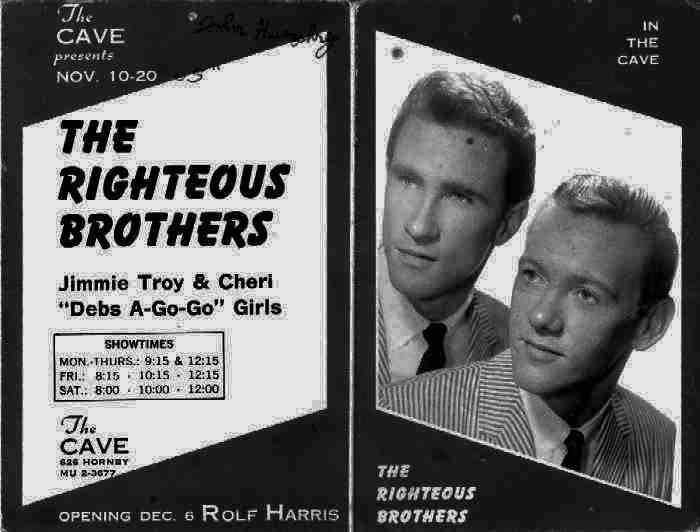

They would also allow children in with their parents, though they wouldn’t serve them. Vancouver ESL instructor Kari Karlsbjerg says she will never forget the evening—she thinks it was in 1973 —that “my mom and I dressed up in our party dresses and went to the Cave to see the Righteous Brothers. I was only seven years old, and it was my first time seeing live music. As the tuxedoed waiter took us to our table, I remember taking in the sights of the smoking and drinking elegant crowd, the cavernous room and stalactites, with open-mouthed awe and wonder. Our balcony table overlooked the stage, so we could clearly hear every perfect note of ‘Unchained Melody’ and see every strand of their perfectly feathered ’70s hair. I am so grateful I had a chance to experience such a unique landmark.”

The Righteous Brothers gig poster for their 1965 Cave appearance.

Tales from the Cave will continue in Part 2 with stories from Rob Frith, David M., Nick Jones, and Joe Keithley. Read more stories of Hidden Vancouver.