Due to COVID restrictions, this year’s Polar Bear Swim will look a little different. Rather than gathering at English Bay, the Vancouver parks board encourages participants to fill their bathtub or a kiddie pool with cold water and share their dip digitally. You can register here, or stay dry and toasty and read this story from our archives on how the infamous swim began.

The Polar Bear Swim is for the athletic and the aquatic, for the partygoer and the masquerader, for the daring and the dipsomaniacal. These days, more than 1,500 people regularly plunge into the brisk saltwater of English Bay, while many thousands more salute from the only slightly warmer shoreline. Liquid intoxicants are not unknown among the celebrants.

The annual dip marked its 100th anniversary last New Year’s Day. The event has grown from a spontaneous lark enjoyed by a handful of friends into a city-sponsored festival complete with official merchandise, including toques and totes.

It takes a hardy—or, perhaps, foolhardy—swimmer to doff clothes to enter water ranging from a chilling 9-degrees Celsius (48-degrees Fahrenheit) to a hypothermia-inducing 3 C (38 F). For comparison, lukewarm water is at least 36.5 C (98 F). One chilly year, a lifeguard posted a “No skating” sign at water’s edge. Don’t stay in the drink more than 15 minutes, the city warns. A century of Polar Bear Swims has generated plenty of headlines over the years, including an annual count of those needing hospitalization.

Three particularly memorable characters stand out in the Polar Bear Swim’s first century—the swim’s founder Peter Pantages, blind swimmer Ivy Granstrom, and cold-water endurance champion Harry (Ironman) Kovish.

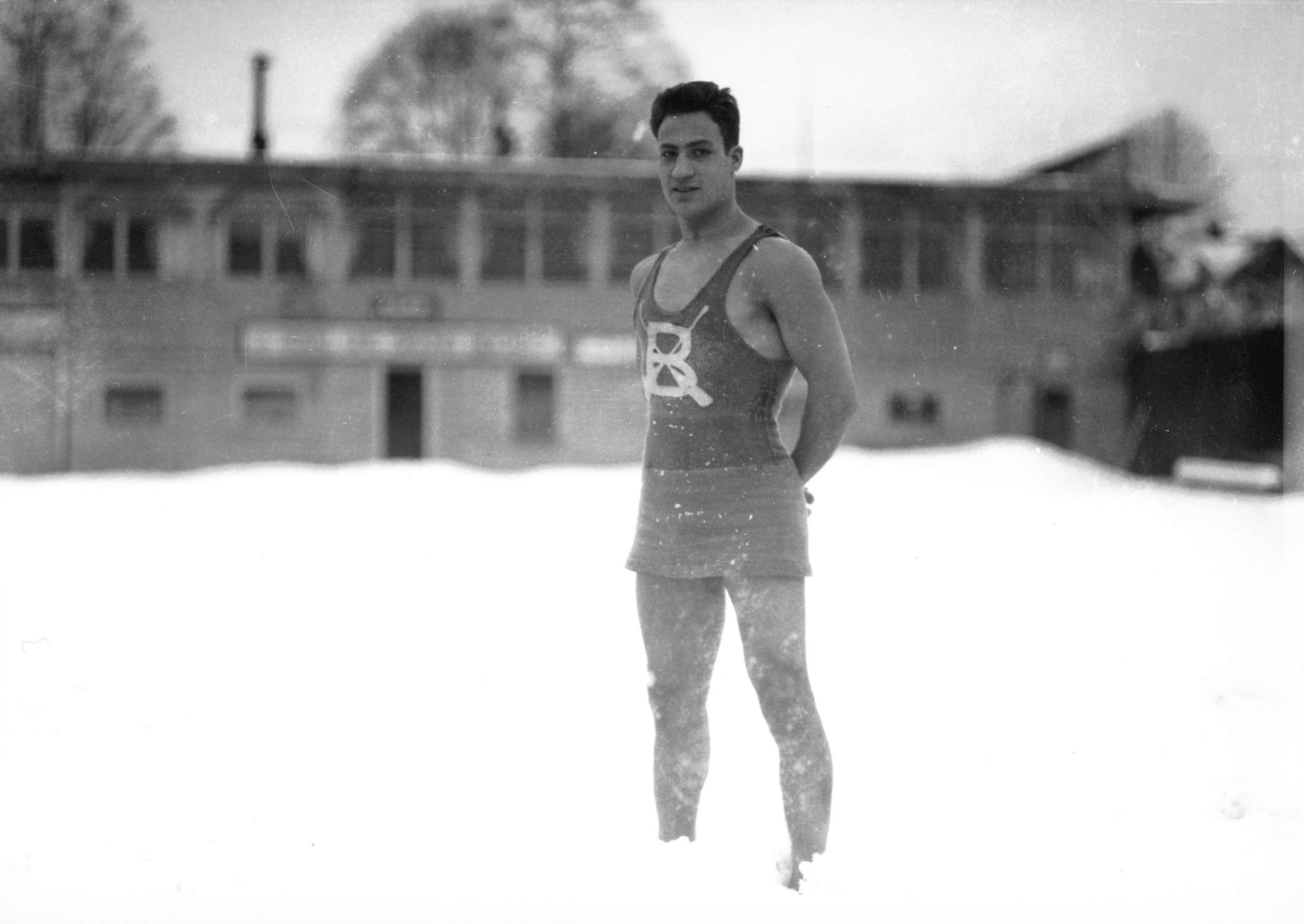

Peter Pantages poses on a snowy beach in 1927. Photo by Stuart Thomson/City of Vancouver Archives CVA 99-1786.

Pantages was born as Pericles Pantazis in Korthio, a town on the picturesque Greek island of Andros. The boy learned to swim when an older brother pushed him off a rowboat and into the Aegean Sea at age four. After he emigrated to North America, where he found work helping run the family’s chain of vaudeville theatres, he was assigned to Vancouver, where he made it a daily ritual, in weather fair or foul, to take a dip in English Bay.

In 1920, nine other swimmers joined him and they formed a tongue-in cheek Polar Bear Swim Club, likely modelled after the one founded at New York’s Coney Island in 1903.

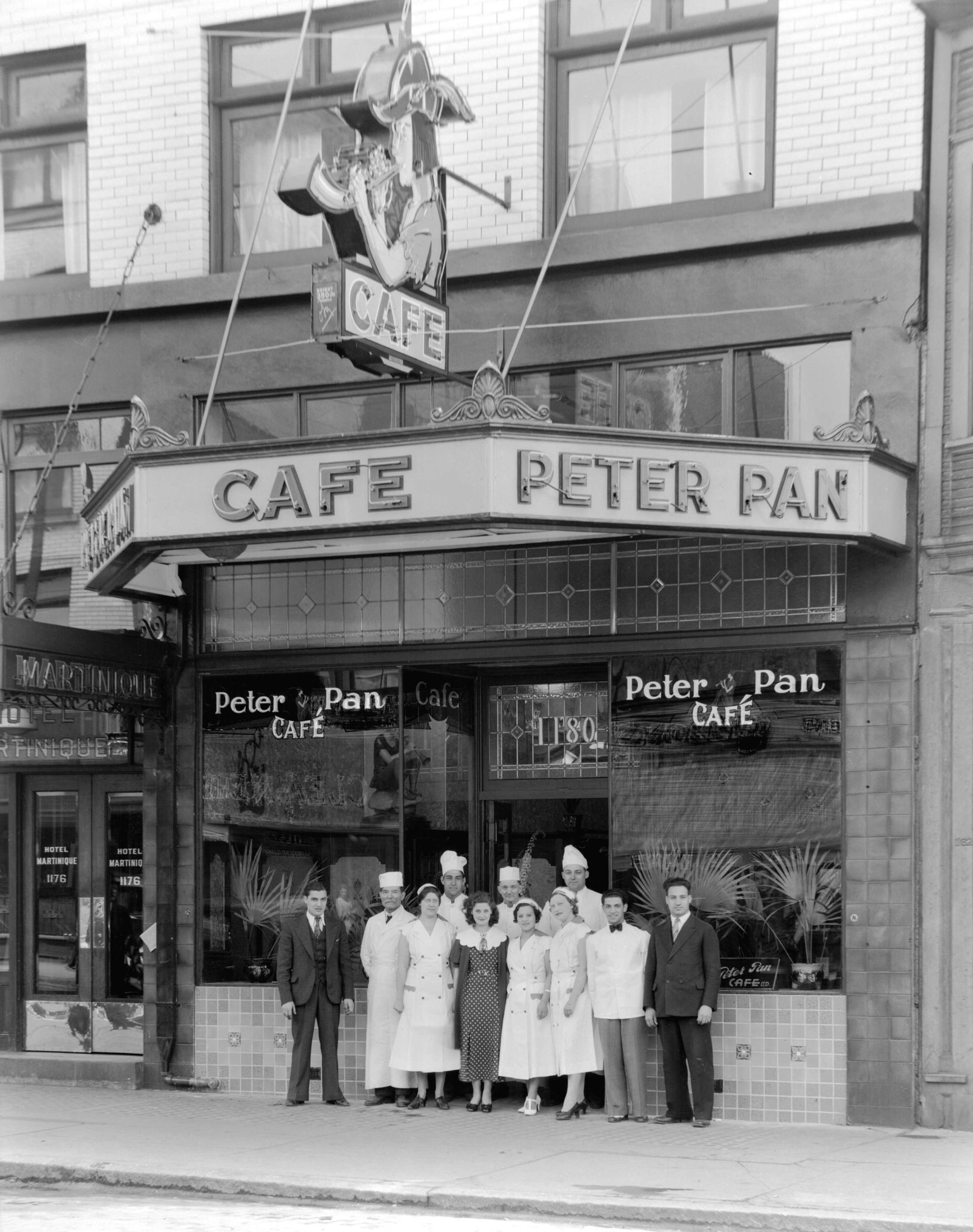

It became an annual ritual for the club to mark the success of the bracing romp by retiring to Pantages’ Peter Pan Café at 1180 Granville Street at Davie for a clambake including hot chocolate and hot toddies.

Peter Pantages poses with staff outside his Peter Pan café on Granville Street in 1934. Photo by Stuart Thomson/City of Vancouver Archives CVA 99-4420.

Pantages was a natural promoter, so both his swimming feats and his restaurants got plenty of press attention from Vancouver’s daily newspapers. Both Christmas Day and New Year’s Day are slow news days, so a caper in freezing water was tailor-made for page one.

It was Pantages’ sad, ironic fate to die while on holiday in Hawaii, where his body was found floating in warm, shallow water off the Halekulani Hotel on Waikiki Beach in Honolulu. It was thought he had suffered a heart attack. He was 69.

The Polar Bears were an exclusive club with few members until the post-war years, when the frigid frolic caught the public imagination. The Vancouver parks board took over operations, and official charities were named as beneficiaries of various fundraising schemes. In 1954, John Godfrey put on a display of water-skiing tricks while his dog Crackers rode in a wheelbarrow between his master’s skis. Godfrey did so while wearing a B.C. Lions football uniform to promote the new professional team.

One of the regulars at the swim was Ivy Granstrom, the youngest of seven children from Fernie, B.C., where she began work at age 12 as a cleaner and cooker for miners. Born with fading eyesight which left her legally blind as a child, she trained as a nurse during the Second World War and worked as a waitress at the White Lunch and the Hotel Vancouver. She took her first polar dip at age 16 in 1928 and never, ever missed a swim.

By the 1990s, the Queen of the Polar Bears was granted the honour of being allowed to take the first plunge before the exuberant, drunken horde stampeded giddily into the surf. Her final plunge took place at age 92 in 2004, her 77th consecutive swim.

The first press star of the swim was Harry Kovish, a Saskatchewan-born sound engineer who won eight consecutive endurance trials before retiring as undefeated champion. In those early post-war years, only a few dozen swimmers accepted the challenge, so he needed only to stay in the water for about a half-hour. His exploits were dutifully covered by the Vancouver Sun, as well as the Jewish Western Bulletin. Kovish thought nothing of posing atop blocks of ice, or lying on the beach to be covered by shaved ice.

In 1948, Kovish was challenged by a self-described Armenian strongman named Kirkor (or, according to various newspaper accounts, Kirko, Kriker, Kribor, or Kriskor) Hekemian (or Hekiminian) in an endurance swim. The stunt, billed as a Cold War, got plenty of ballyhoo from the papers and it was decided to make the charitable March of Dimes a beneficiary.

Hekemian, who called himself The Human Polar Bear and The Strong Man of the North, had made a few dollars (and headlines) over the years by plunging into Regina’s icy Wascana Lake, or Montreal’s floe-filled St. Lawrence River, or Alberta’s High River, into which he had to cut a hole like an ice fisherman before immersing himself clad only in bathing trunks, his body covered in grease.

Ironman Kovish, who was called Old King Cold, handily won the shivering showdown.

So this New Year’s Day, raise a toast to all the polar bears who join Lisa Pantages, Peter’s granddaughter, in greeting the year through chattering teeth.

This story from our archives was first published on Dec 30, 2019. Discover more local history.