This story is the 15th in our series on the hidden history of Vancouver’s neighbourhoods. Read more.

In January 2024, Vancouver city council approved a plan led by the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh Nations (through their MST Development Corporation) to redevelop the Jericho Lands, a 36-hectare parcel of land that includes the long-defunct Jericho Garrison site, into an ambitious development that would add highrises and 24,000 new residents to the quiet beachside neighbourhood of West Point Grey.

Some residents were predictably displeased. If you’re going to pick one Vancouver neighbourhood that’s change-averse, it might be this affluent area, bounded by Alma Street to the east, Blanca to the west, West 16th Avenue to the south, and English Bay to the north. As the rest of the city has grown, Point Grey’s population of about 13,000 has barely budged in the past three decades. And yet the way West Point Grey is changing harkens back to its origins as a site of cultural exchange, commerce, and development.

The story of this neighbourhood begins with its First Nations history. According to Pauline Johnson’s Legends of Vancouver, the area’s original resident was the Great Tyee, the god of the west wind and ruler of the Salish Sea. After failing to usurp the Sagalie Tyee, he was turned into Homolson Rock, which stands near the Point Grey shoreline. Near present-day Locarno Beach once stood a Musqueam village called Ee’yullmough, which means “good camping ground.” Present-day Jericho was then dominated by a salt marsh filled with birds and offering First Nations people salmon and trout as well as sea vegetation.

The late 18th century brought visits from European sailors, who foisted their surnames on the local geography. In 1791, Spanish sailors named the area Punta de Langara. The next year, a chance meeting of Spanish and English sailors inspired the current names of Spanish Banks and English Bay. The leader of the English expedition, George Vancouver, named Point Grey for his friend George Grey, a fellow member of the British Royal Navy.

For another half century, Europeans left this area alone until, in 1865, the hillside fir trees caught the attention of New Brunswick-born logger Jeremiah Rogers, who built a logging camp on the beach that later became known as Jerry’s Cove, later garbled into Jericho. In the 1870s, a whaling station was established on the beach. Until recent decades, the neighbourhood’s beaches have often been scouted for further industrial applications. Jericho and Spanish Banks were part of a proposed megaport in the early 20th century. And as late as 1950, Spanish Banks was considered for a potential airport site. (Jericho also sits near one of the relics of the city’s industrial origins, the old Hastings Mill Store, which was preserved and shipped by barge from its original location in the Downtown Eastside in 1930.)

While a tennis club and sailing centre flourish there now, people came around slowly to the beach’s eventual identity as a destination for relaxation. In the last half of the 19th century, picnickers began boating across English Bay to Jericho. In 1892, the Vancouver Golf Club was founded in the sand dunes, with tomato cans for holes.

That same year, Point Grey was incorporated into the municipality of South Vancouver, then seceded, in 1908, from working-class neighbourhoods like Marpole and Sunset (originally called Eburne Station and South Hill respectively at the time) to form its own municipality, Point Grey, with residents of Kerrisdale, Dunbar, and Shaughnessy, establishing itself as a location for the city’s upper crust. Before amalgamating with Vancouver in 1929, Point Grey introduced infrastructure improvements and a tax on undeveloped property that, combined with the growth of UBC to its west and a streetcar expansion, launched Point Grey Village, a commercial strip on West 10th Avenue. One grand home from that era is Aberthau Mansion. Completed in 1913, the Tudor-style house on West 2nd Avenue was a private residence and then the Royal Canadian Air Force officers’ mess hall during the Second World War before taking its present form as the West Point Grey Community Centre in 1974.

A long-running military presence in the neighbourhood began in the 1920s with an air force base at Jericho Beach. Pilots patrolled the skies in search of rum runners and illegal fishing boats. During the Second World War, the base served as the headquarters for the Canadian military’s Pacific operations, commandeering the golf course clubhouse and British Columbia School for the Deaf and Blind’s building during the war, while also creating new buildings still in use today as a youth hostel, an arts centre, and the Jericho Sailing Centre.

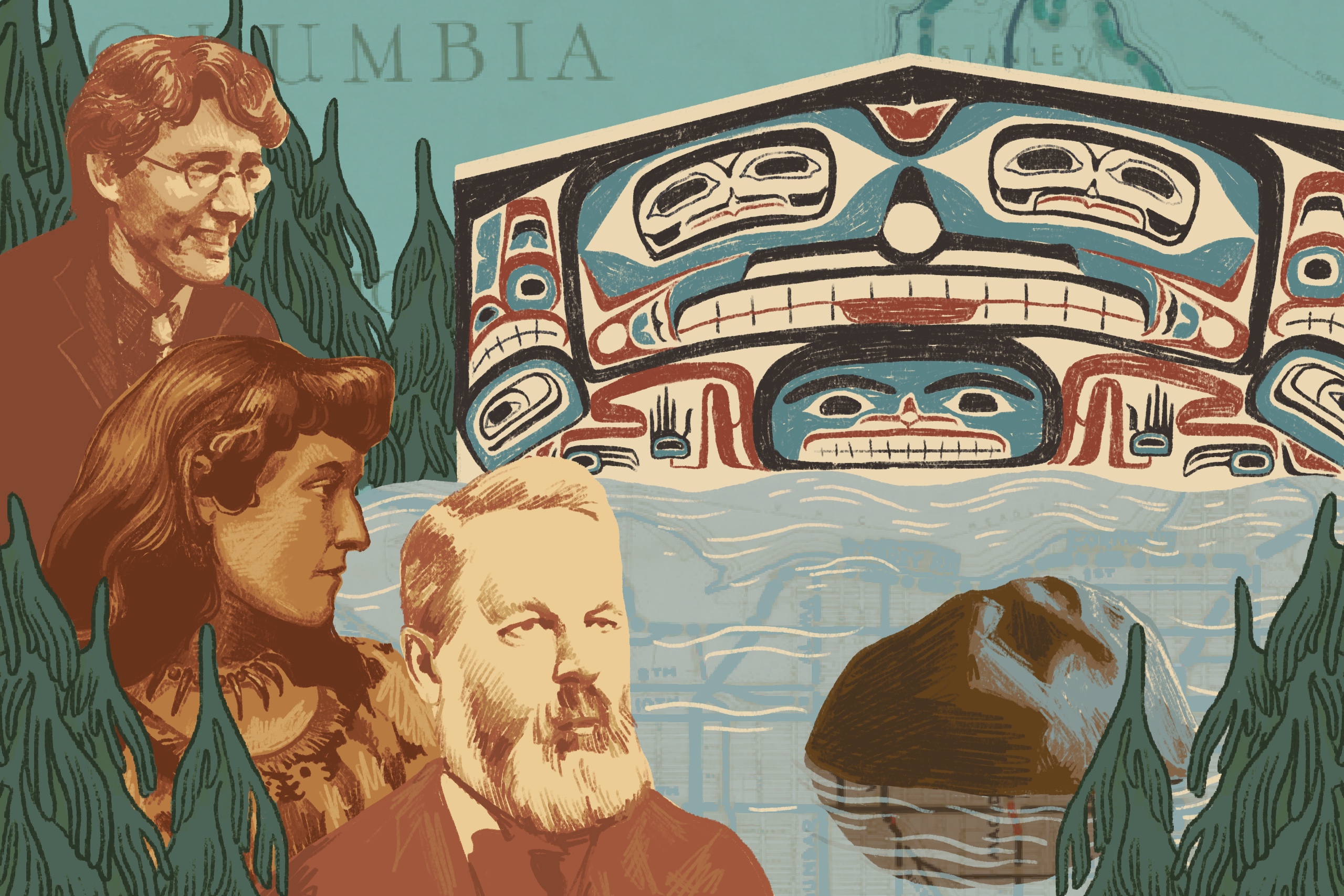

After the federal government returned beachfront land to the city in the late 1960s, the site’s abandoned aircraft hangars were refurbished and repurposed, including with a new mural by Bill Reid, into the site for Habitat ’76, or the first-ever United Nations Conference on Human Settlements, which focused on, among other things, population growth and housing. “Habitat ’76 was a very big deal,” local historian Eve Lazarus writes on her blog. “It ran at Jericho Beach Park from May 27 to June 11, 1976. Pierre and Margaret Trudeau were there, and so were Mother Theresa, Margaret Mead, and Buckminster Fuller.” Ironically, the retrofitted aircraft hangars, meant to show how the lives of buildings could be extended, were either bulldozed by the Parks Board or lost to mysterious fires (the kind that seem to so commonly afflict inconveniently placed structures in the city).

Until the past decade, the Canadian military’s presence continued farther south on the Jericho Garrison on West 4th Avenue, where the province’s reserve units were administered and housing was provided for military personnel and their families. In 2014, the land was jointly purchased by the MST Development Corporation, which also solely bought the adjoining Jericho Hill parcel, and the Canada Lands Company (a Crown corporation).

One of the tenants on this site is the West Point Grey Academy, a private school founded in 1996. Its most famous teacher is Canada’s current prime minister, Justin Trudeau, who taught math, humanities, social studies, French, and drama from 1999 to 2001 and made one of his infamous “blackface” appearances at an “Arabian Nights”-themed school fundraiser in 2001.

As the Jericho Lands development ushers in new demographics and trends, the neighbourhood’s one-time hub, Point Grey Village, finds itself struggling to survive. The commercial drag on West 10th Avenue, once the home of a movie theatre, a Safeway, and a schnitzel house, has hollowed out as improved amenities at UBC and an aging population have made these businesses less viable. Last March, the city received an application to redesign the site of the now-gone Safeway into a collection of rental apartments with over 500 units. “To bring the village back to life will require imagination and creative thinking,” says academic and writer Jean Baird, chair of advocacy group Friends of Point Grey Village, about the development. She goes on to say the development is “too big,” noting that “You don’t plunk a fortress down in the middle of a village.”

West Point Grey, once a stronghold in the country’s defence systems, finds itself again in the middle of a war.

Read more Vancouver Neighbourhood stories.