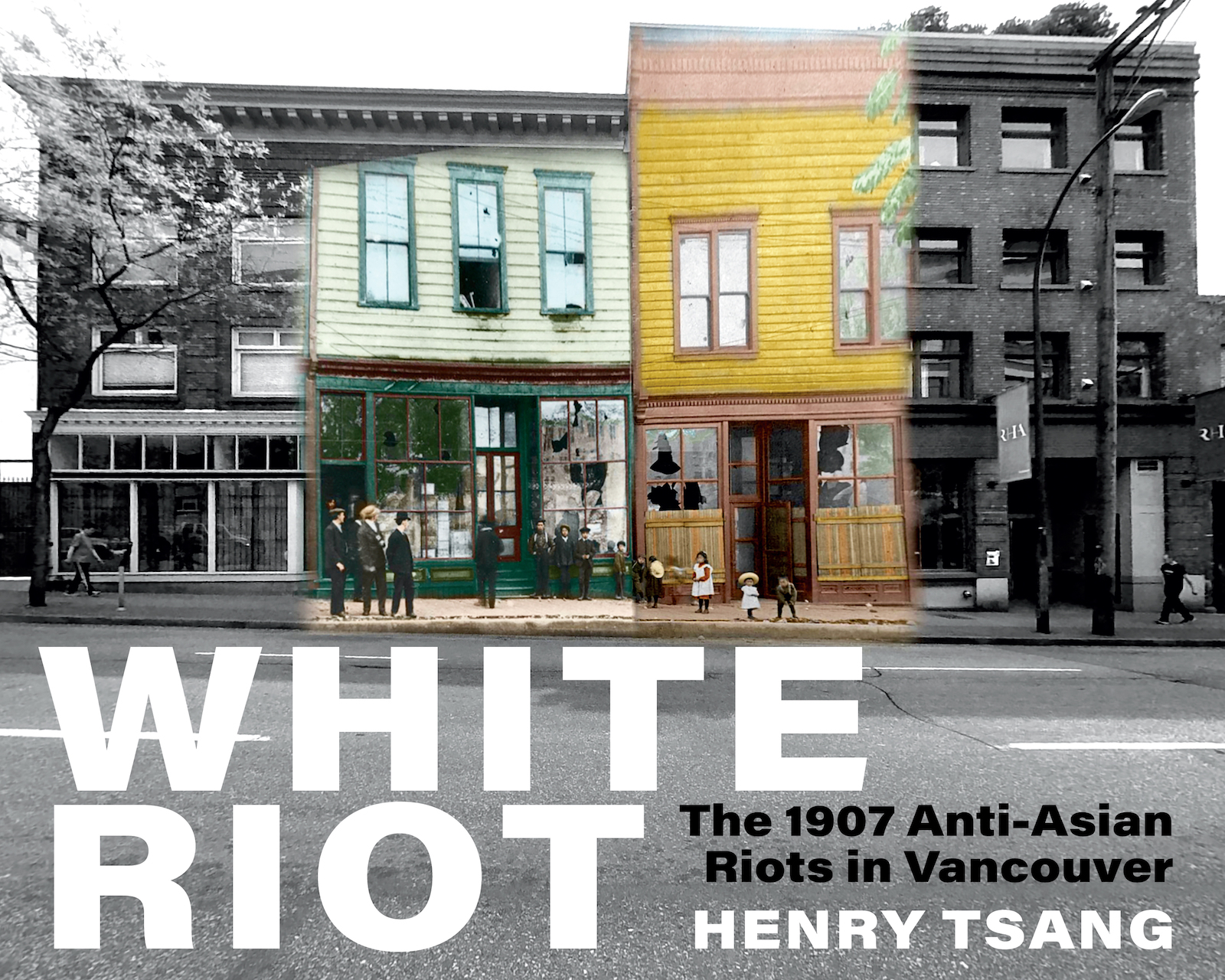

Author and artist Henry Tsang created the 360 Riot Walk interactive tour, which traces the route angry mobs took as they attacked Vancouver’s Chinese Canadian and Japanese Canadian communities in 1907. Tsang’s new book, White Riot: The 1907 Anti-Asian Riots in Vancouver, explores the causes—and continuing effects today—of this racist violence through photographs and essays, such as this piece by Angela May and Nicole Yakashiro.

360 Riot Walk traces the layered histories of Vancouver’s labour politics, anti-Asian racism, and community resistance in what is today known as the Downtown Eastside (DTES). One of the tour’s key sites is the historic Powell Street neighbourhood, a target of rioters in 1907 and the former hub of the city’s Japanese Canadian community before the federal government uprooted and dispossessed thousands of Nikkei (members of the Japanese diaspora) residents in the area, beginning in 1942. Talking and walking about these places may seem like nothing much at all, but we suggest that the ways we do so matter. Even the names we give these places shape how we understand their history, their present, and their possible future. This is why we say Powell Street and not “Japantown.”

Why Do People Say “Japantown”?

The name “Japantown” pervades popular media. You can find it on Google Maps, in newspaper articles, podcasts, and up until recently, in the City of Vancouver’s heritage documents. One Daily Hive story, for example, draws on photographs to depict what the writer describes as “Vancouver Then and Now: Japantown.” Even the popular CBC podcast The Secret Life of Canada dedicated an entire episode in 2020 to ask: “Where Is Japantown?” To some extent, the use of “Japantown” makes sense. It is an easy-to-recognize moniker that fits within a historical landscape of migrant or “ethnic” enclaves in Vancouver and, more broadly, Canada. Perhaps most well known among these neighbourhoods in Vancouver is Chinatown, a place that has also faced its share of targeted violence and whose residents continue to confront aggressive threats of gentrification. From their very beginnings, white settlers and politicians gave these neighbourhoods—often composed of working-class migrant communities—names like “Japantown” or “Little Tokyo” to mark them as “foreign” and outside the bounds of white settler society. But these sites were never the sole creation of outsiders. Rather, migrants constructed these neighbourhoods as places of respite and community in spite of the onslaught of anti-Asian racism and other forms of class and race-based marginalization in settler colonial Vancouver. Over time, even the names of these places have been reclaimed by communities and deployed in new ways. Chinatown, for example, has become a name and place around which many Chinese Canadian community organizers have mobilized throughout the twentieth century. These names, then, have become commonplace and appear to many as innocuous and even empowering.

But Why Exactly Is “Japantown” A Problem, Then?

While we recognize the power of invoking place names for community-organizing purposes, we also question their limitations, specifically in the case of “Japantown” in Vancouver. We find ourselves asking: What does the name “Japantown” obscure? How is “Japantown” used and misused? How has it been deployed, and by whom? Historically, “Japantown” was never used widely among Japanese Canadians living in Powell Street before the Second World War. Instead, they more often used “Paueru Gai,” “Powell Street,” “Powell Grounds,” or simply “Paueru.” Also, Japanese Canadians were never the only people to live and work in the Powell Street area. The name “Japantown” obscures the presence of non-Japanese neighbours, tenants, co-workers, and friends, never mind those within our community who do not identify with Japan. The neighbourhood has always been diverse and, more importantly, has “long served as a place for people [and communities] facing structural and quotidian violence in settler colonial Vancouver.” As Nikkei artist Andy T. Mori reminds us, “The Nikkei obviously weren’t the first to be violently displaced out of the area. The DTES was one the earliest places of Indigenous settlement in what became Vancouver.” Moreover, as a result of the forced incarceration, dispersal, and dispossession during the Second World War, Japanese Canadians simply no longer live in Powell Street. This fact, the racist origins of the name, and the multiple erasures the name perpetuates makes calling the Powell Street neighbourhood “Japantown” a problem.

270 Powell Street, labour agents, 1907. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, PA-067272.

Perhaps most critically, the use of the name risks people’s displacement from the neighbourhood. While for some, calling Powell Street “Japantown” is a way to commemorate and claim the neighbourhood as a Japanese Canadian place, others—namely urban planners, policymakers, and politicians at the City of Vancouver—have capitalized on our community’s desire to commemorate the neighbourhood to justify gentrification in Powell Street. If we take seriously the power of names and naming, we must reckon with the difficult fact that “Japantown” has been mobilized by the City and by developers in order to “revitalize,” “clean up,” and “beautify” Powell Street at the expense of people currently living in the area. This kind of “revitalization” project is perverse, because it recognizes the violence and injustice of the uprooting of Japanese Canadians, but in the same move—literally in the name of commemorating wrongdoing to Japanese Canadians—facilitates further violence and injustice by displacing low-income, often Indigenous, racialized, disabled, and gender nonconforming people who live in the neighbourhood.

The problem of the term “Japantown,” then, is both straightforward and complicated. The name proposes a kind of Japanese Canadian commemoration that lays the groundwork for further violence in the neighbourhood: it commemorates Japanese Canadian presence and facilitates other people’s absence. In Vancouver, should we continue to use the name “Japantown,” we would be complicit in yet another iteration of violent displacement in the very place from which we were once forcibly removed. Saying Powell Street and not “Japantown” reflects our refusal to take part in that displacement and our commitment to reckoning with the consequences of our community’s history-telling.

But Can A Name Really Cause Harm?

Yes—and we are far from the first to raise concerns about the name “Japantown.” For decades, a wide range of Japanese Canadian academics, artists, and writers have considered this very issue, and yet, it remains an ongoing problem. For instance, from 2012 to 2015, geographers Jeff Masuda, Audrey Kobayashi, and Aaron Franks led a research project called Revitalizing Japantown? A Unifying Exploration of Human Rights, Branding, and Place. These scholars explicitly questioned the politics of place names in Powell Street and, alongside a team of other researchers, artists, activists, and organizers in the Japanese Canadian and DTES communities, were able to interrogate how “Japantown” was mobilized in urban planning. They found that, by and large, the use of the name “Japantown” was synonymous with the desire to gentrify Powell Street, paving the way for displacement across the neighbourhood. The project located the specific origins of the place name “Japantown” in the 1980s when the City of Vancouver sought to create a “Japanese Village” in the DTES in the name of “beautification.” Decades later, in 2012, even the City’s Local Area Planning Process, an initiative said to address issues of homelessness and displacement in the DTES, “appropriate[d] [Japanese Canadian] history to advance an exclusionary ‘Japantown’ revitalization agenda.”

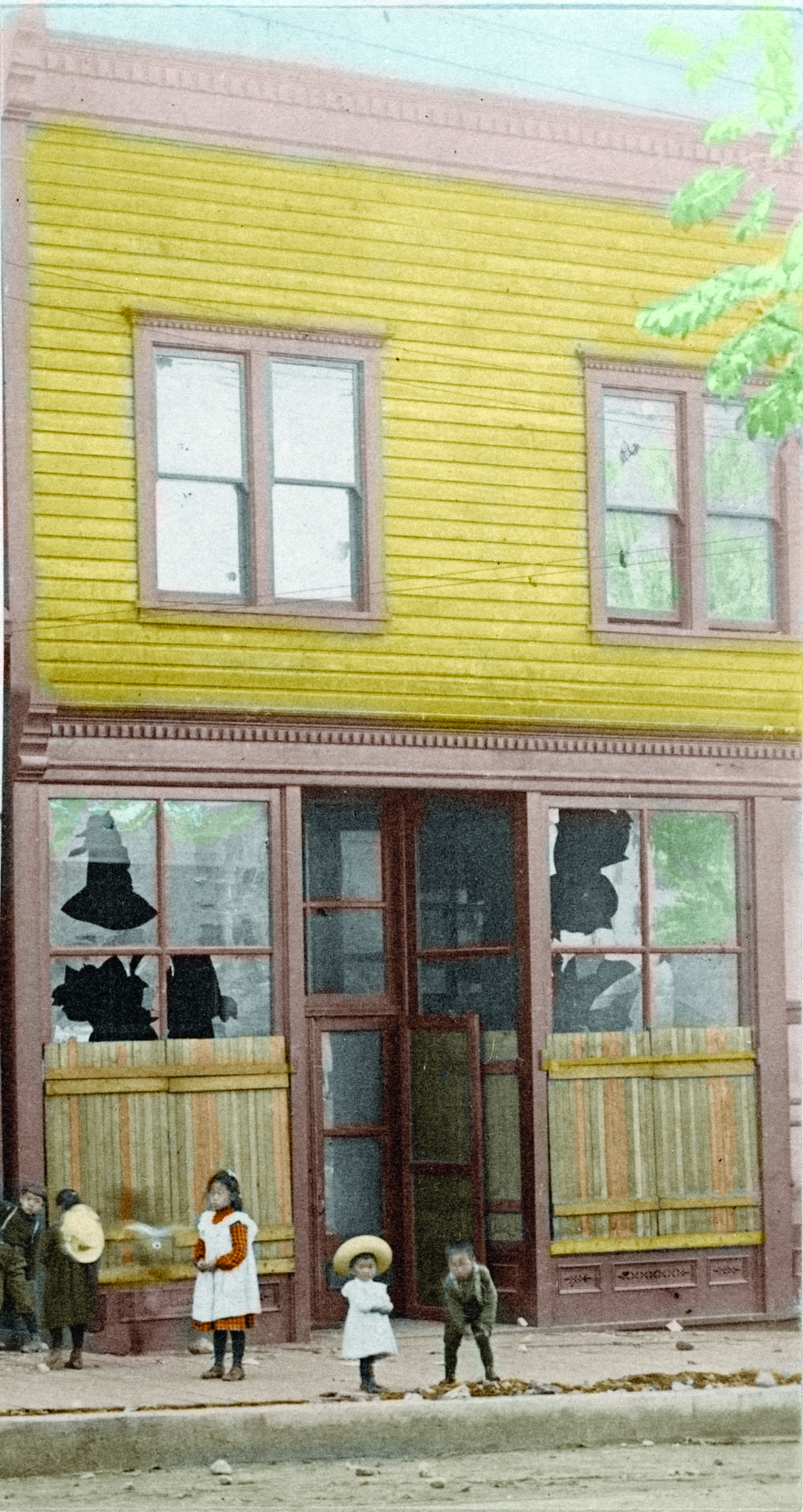

122 Powell Street, 1907. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa, PA-067275.

For many within the Japanese Canadian and DTES communities, this “revitalization” agenda was wrong. As the Revitalizing Japantown? museum exhibit catalogue later put it, “The DTES is its people, and the people of the DTES do not need to be ‘revitalized’ because they are already vital.” This sentiment echoes earlier work from Audrey Kobayashi in which she underscores the DTES community’s “vibrancy and rhythm” and stresses how they too are “undergoing a dispossession, daily eroded as the pressures of rising property values yield more and more buildings to the avarice of developers.” As Nikkei scholars who owe much to the scholarship and activism of Japanese Canadians before us, what we articulate here is an expression of our inheritance: the place name “Japantown” must be refused.

So, What’s Next?

We move forward by questioning the names we use to describe the places we inhabit and move through—including the places featured in 360 Riot Walk. At stake are the lives and livelihoods of people now dwelling in the Downtown Eastside. We cannot advocate for justice or redress without addressing the ways injustice is perpetuated in our community’s name or in the name “Japantown.” To attend to the meanings inherent in 360 Riot Walk and to think through the question posed by artist Henry Tsang of who has the right to live here—both in the Downtown Eastside and on all unceded xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish), and səl̓ilwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) lands—we need to grapple with the fact that how we inhabit places and the names we give them are not benign. On the contrary, the ways that we take up and name spaces are meaningful decisions and forces. Words and names do things. Even as we advocate for the name of “Powell Street” or “Paueru Gai” in lieu of “Japantown,” we know this name is far from perfect itself. Powell Street itself was named after Israel Wood Powell, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in British Columbia from 1872 to 1889, a fact which prompts us to further question the politics of names and commemoration in settler colonial Canada. What and whom does the name “Powell Street” obscure?

360 Riot Walk tour participant, 2019. Photo by Henry Tsang.

But the thing about names is that we can change them. We can adapt. We know that the name “Japantown” does things and that the things that it does are violent. We refuse to let our history be weaponized against the Downtown Eastside. Some may read this and ask what the Japanese Canadian community might lose by rejecting the name “Japantown.” We ask, instead, what we—and so many others—can gain. This is why, at least for now, we say Powell Street and not “Japantown.”

Reprinted with permission from White Riot: The 1907 Anti-Asian Riots in Vancouver by Henry Tsang (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2023).

Read more book excerpts.