The late great architect Bing Thom believed architecture is a vehicle for something greater—beyond the function of brick and mortar. In this story from our archives, we look back at Thom’s design legacy locally and around the world.

Bing Thom’s favourite answer to a question he was asked often—what is your favourite building—was always, “My next one.”

The talented and groundbreaking Vancouver architect passed away unexpectedly on October 4, 2016 in Hong Kong, with his wife Bonnie at his side. He was 75.

Those he left behind—his colleagues, his friends, his family, and his city—have had a short time to process his loss and legacy, and that legacy is similar to how his firm describes architecture itself: “A meaningful whole made of many divergent parts.”

Bing Wing Thom was born on Oct 8, 1940 in Hong Kong. He and his family immigrated to Vancouver in 1950. He attended the University of British Columbia and received a Bachelor of Architecture in 1966, and a Master of Architecture in 1969 from the University of California, Berkeley. According to colleague and Bing Thom Architects principal Michael Heeney, it was at Berkley that Thom became a “bit of a radical”—a quality that would help define his approach to architecture later in his career.

Guildford Aquatic Centre. Photo by Ema Peter.

He moved to Tokyo in 1971 to work for Japanese architect and urbanist Fumihiko Maki. Then in 1972, Thom returned to Canada and started as a project director for Arthur Erickson Architects. During his time with both Maki and Erickson, Heeney believes Thom “learned through exposure to them both about the power of architecture. How creating something timeless and beautiful transcends its utilitarian purpose. Bing said, ‘Architecture is a vehicle for something greater’—he felt its job was beyond its function as brick-and-mortar structures. He wanted people to pass his buildings and be curious about them from the outside, and after they went inside, to emerge feeling taller than they did before they went in. He wanted to elevate people’s confidence and experience.”

In 1982, Thom created his namesake firm, Bing Thom Architects (which was later renamed Revery Architecture after his death). The internal environment was important to him, and he instilled it with his priorities of place-making and community contributions. Bing Thom Architects was often referred to as “graduate school,” in which teaching was as important as the projects that were executed.

Sunset Community Centre. Photo by Nic Lehoux.

“He wanted us all to think beyond the traditional role of an architect,” says Heeney. “He was a wonderful teacher, not just about the projects, but about the bigger questions he sought to answer with his designs: questions of community, cities, development, and engagement. He encouraged us to participate in the communities in which we lived.”

“Bing said, ‘Architecture is a vehicle for something greater’—he felt its job was beyond its function as brick-and-mortar structures.”

He opened additional offices in Hong Kong, and Washington, D.C., bringing his designs to a larger audience. “For such a well-known architect in Vancouver, he actually didn’t do a lot of building in his own city, but he brought elements of Vancouver-inspired design to international attention,” Heeney explains.

Surrey City Centre Library. Photo by Ema Peter.

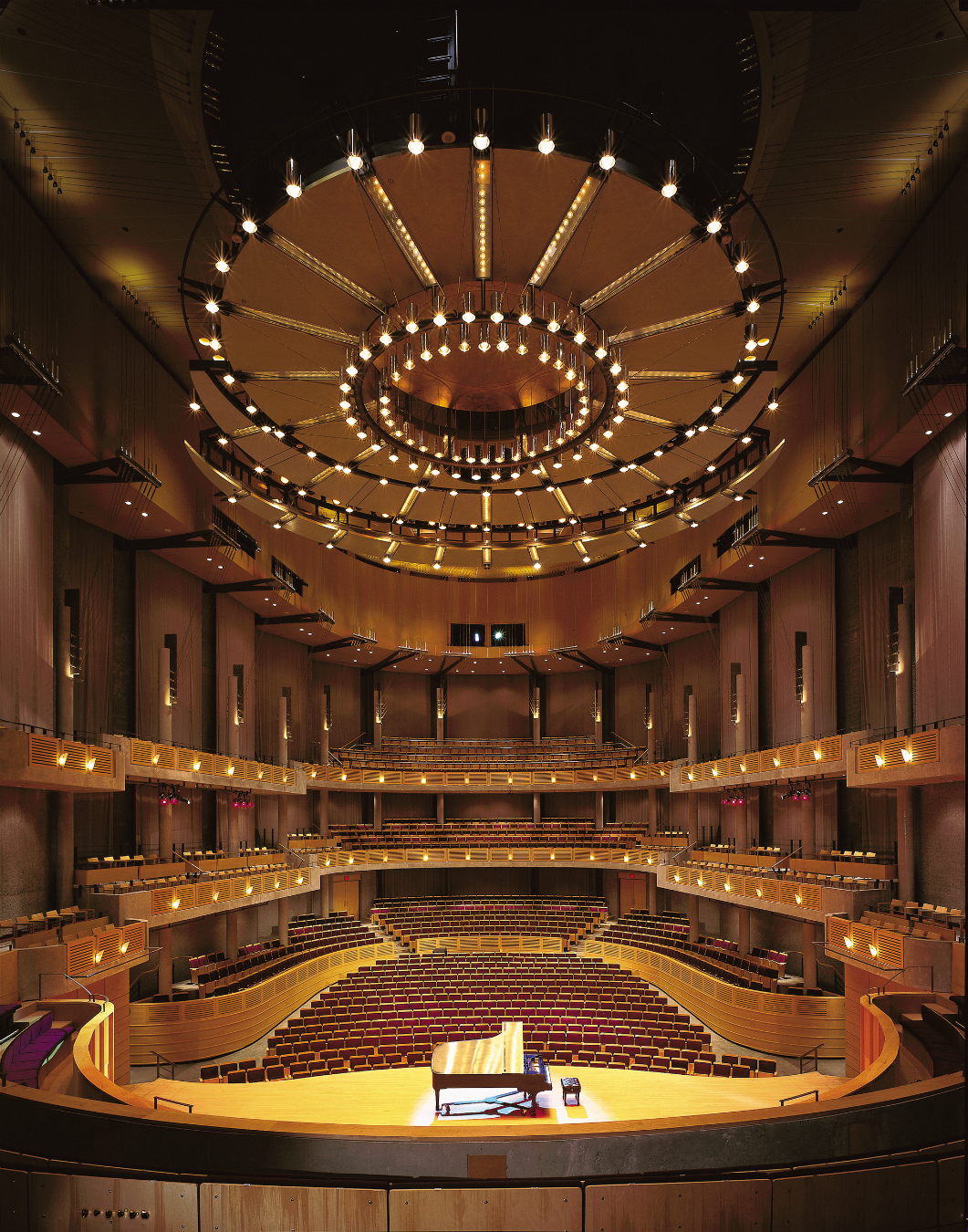

The firm began projects in places like Seville, Spain; Fort Worth, Texas; and Hong Kong. In all cities, he took on any project that inspired him, from personal residences to civic structures. In Vancouver, he built the Chan Centre for the Performing Arts as two drum-like structures, poised on the edge of the Point Grey cliffside; he covered them in Virginia creeper and surrounded them with cedars to allow the enormous performance space to blend into the West Coast landscape, as though it had always been there.

From 1995 to 2015, Thom and his firm took on several major urban projects, specializing in mixed-use structures that created neighbourhoods and street life, with a particular focus on how people use space. “The Surrey City Library design actually increased the self-confidence of the city,” Heeney says. “There was a marked psychological and physical change to the neighbourhood that impacted how Surrey felt about itself, so much so they actually changed their city logo from a crest to an outline of the building.”

Chan Centre for the Performing Arts. Photo by Martin Tessler.

For such impactful work, there were awards: Thom was made a Member of the Order of Canada in 1995 and was a recipient of the Golden Jubilee Medal for outstanding service to his country. He was a Fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, and received honourary degrees from the University of British Columbia and Simon Fraser University. Prior to his death, Bing Thom Architects had begun work on the University of Chicago Centre in Hong Kong, melding the building into its lush surroundings in what had become part of the firm’s signature style.

With Thom’s unexpected death, the firm’s dedicated staff have allowed themselves a brief respite before honouring their leader the best way they can: continuing his work. “Bing’s legacy will be both the people he surrounded himself with, as well as the people who were affected and changed by his designs,” says Heeney. “It will be in the continued fostering of great talent. Bing Thom Architects will continue his legacy by pushing boundaries and expectations in architecture. We’re busier than ever and we haven’t slowed down, which is how Bing would have wanted it.”

This article from our archives was originally published on November 24, 2016, and updated on May 18, 2021. Read more architecture stories here.