In the 1940s and ‘50s, Vancouver was second only to Shanghai as the city with the most neon signage in the world. Vancouver streets lit up the sky more than Las Vegas. A young city still under 100, Vancouver defined its districts by neon: shopping and hotels on Hastings, entertainment on Granville.

French engineer Georges Claude charged a sealed tube of glass with electrical current that contained inert gas in 1902, resulting in the birth of neon in a malleable form that at first was used as a novelty item. The development of florescent tube coatings in 1926 allowed for an array of multiple colours. Tinkering with the mixtures of gas, as well as the development of phosphor colours during the Second World War, resulted in more shade choices becoming available, and neon as marketing began to take shape. Soon, streets around the world boasted the bright signage on every block.

In the 1970s, LED lights began to slowly take over neon’s territory. Cheaper, quicker, and with countless hues, LED’s rise in popularity led to hundreds of neon signs being removed, thrown away, or donated to museums. (The Museum of Vancouver is home to dozens of vintage signs periodically on display.)

At risk of losing an art form that requires significant training and skill, neon glass benders have had to mix it up. Despite a rebirth in the popularity of neon signs in the last five years, it is still a niche market. New approaches and ideas are required.

Andrew Hibbs of Endeavour Neon is leading the charge. Since inheriting the neon portion of his father’s sign business, Hibbs has made significant strides to bring the essence of neon art—the craftsmanship, quality, time, and artistry—back to the forefront.

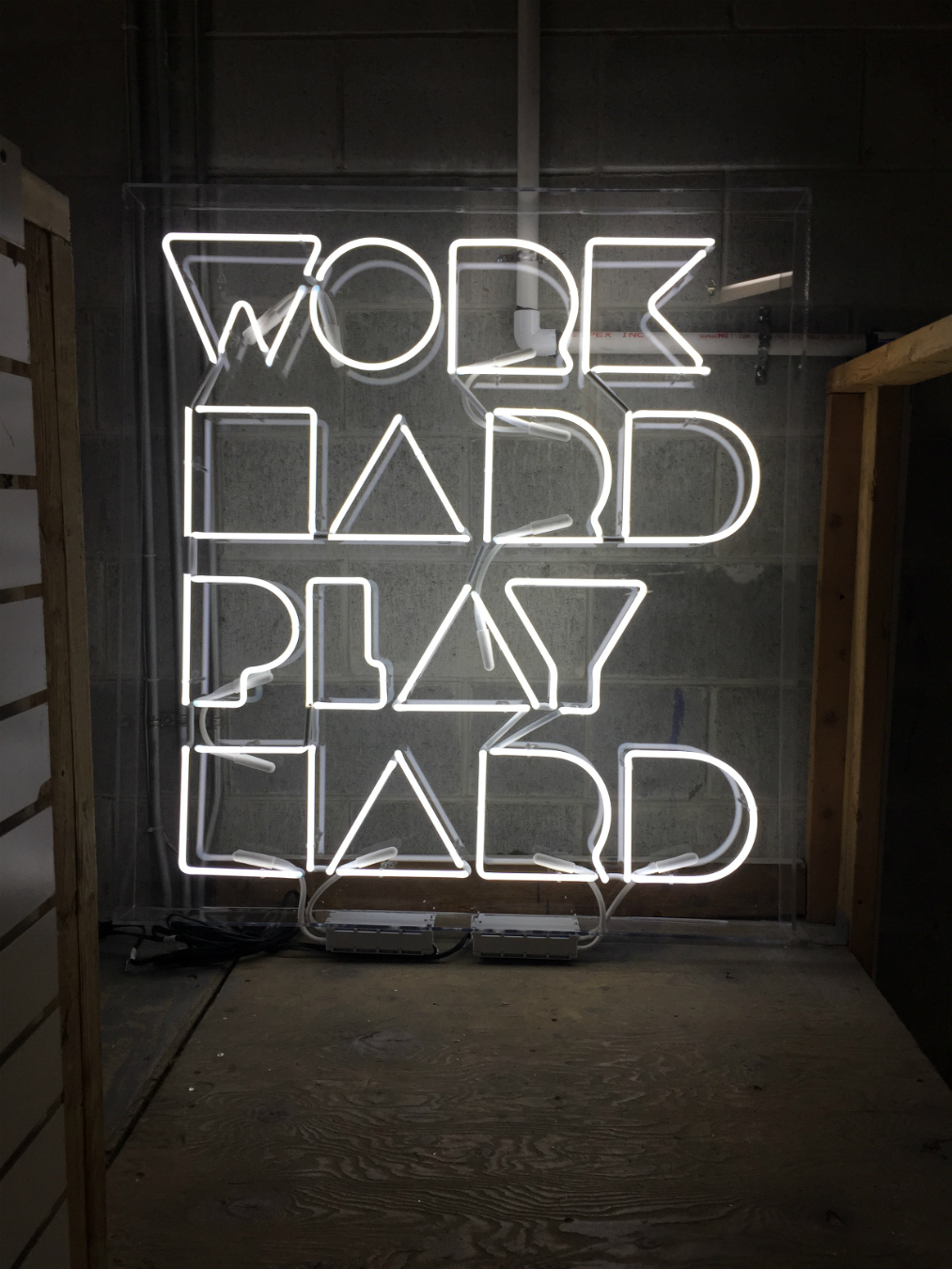

Hibbs’s father taught him to bend glass when he was 13 years old. He started small, making repairs and putting gas in tubes, until he realized it was what he wanted to do for a living. Once the company was in his hands, Hibbs decided to make its neon output more modern than commercial, making mini art installations that could be brought into people’s homes. The creativity of these projects is a collective effort, a realization of a vision between artist and client. So far Hibbs has made logos, favourite sayings, and drawings come to life. “I see neon going more modern, more artsy, people using it for sayings on their wall or night lights for their kid’s room; instead of just for commercial use, it will be a way for people to express themselves,” he says. And judging by the level of demand for his work, he’s right. “The philosophy behind my company comes from my business name, Endeavour Neon, because it means: try hard to do or achieve something,” Hibbs explains. “That is what I strive to do with every sign I create.”

Although it can be frustrating and difficult, bending the glass is the most enjoyable part of the craft for Hibbs. In this respect he hopes to bring back the excellence and workmanship that early sign makers had. Theirs—as well as his—are built to last; tubes are meant to live for decades, and the pieces to be passed down through generations.

Hibbs’s signs are becoming familiar landmarks around the city (Bao Bei’s retro decal and Kit and Ace’s “Time is Precious” installation, to name only two), but don’t ask him to pick his favourite. “I can’t choose just one because I am proud of all the work I do,” he says. “My business is growing and growing; every day I get to create something new. I love that about my job—getting to see ideas brought to life.” Perhaps in the hands of Hibbs we can see Vancouver’s neon reign rise again.