Vancouver, Seattle and Portland are the birthplaces of the West Coast Modern style of architecture. Designed to fit seamlessly into a rainforest climate and their individual surroundings, midcentury West Coast Modern homes dot our neighbourhoods with expansive windows and dramatic, clean lines that are an inherent part of the visual identity of our city.

One of the most significant examples is West Vancouver’s Forrest House in the British Properties, built by Canadian architect Ron Thom in 1962—and it’s on the chopping block.

The house’s latest owner wants to demolish it, but the District of West Vancouver has not yet received any applications for a new build on the land. The district’s council voted in November to pause the proposed demolition for 60 days to give staff more time to study the application and possibly find an alternative, while a local heritage group has also jumped in to try to save the property.

“This was the most important piece of modernism when it won the Massey Medal in 1964. It’s very significant,” says Kathleen Staples, executive director and founder of the non-profit Binning Heritage Society.

The Forrest House on Eyremount Drive in West Vancouver. Courtesy of the District of West Vancouver.

Ron Thom’s daughter Emma is one of 4,100 people and counting who have signed the Society’s online petition to save the house. “It is a perfect example of a building blending with its site, a concept that was at the centre of his architectural vision,” she wrote. “It should be preserved and not torn down to make way for yet another tasteless McMansion.”

But time is running out: the district council meets on January 13, and the halt to the demolition expires on January 16. The house is not under heritage protection, though it appears on the West Vancouver Community Heritage Register, which lists properties not legally protected, but recognized as significant.

District staff are still hoping for a positive outcome; they’re in discussions with the owner’s representative right now.

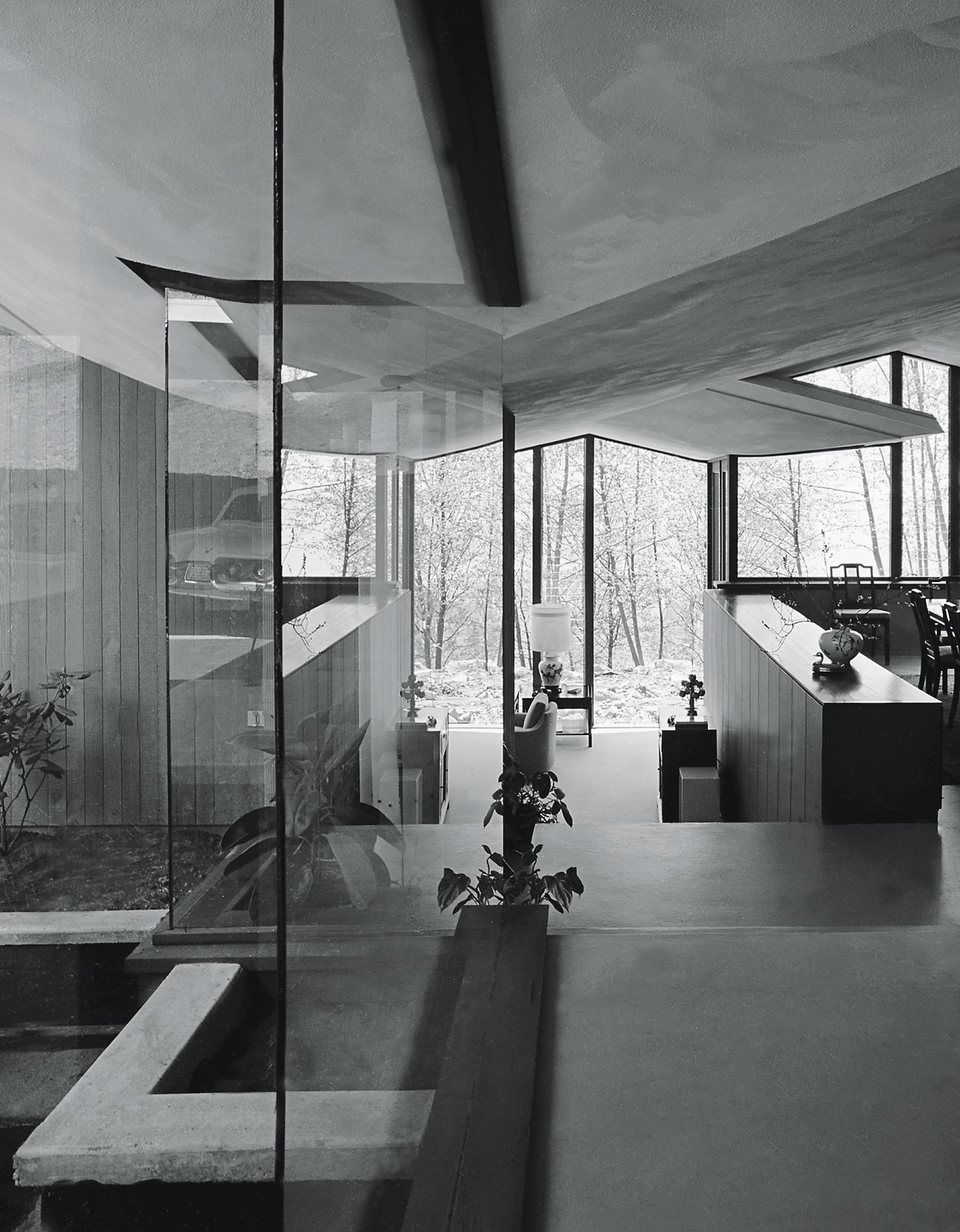

The Forrest residence interior, 1962. Photo by Selwyn Pullan/Courtesy of the West Vancouver Art Museum.

“There were discussions planned before Christmas and this week, and I expect that those discussions will continue until the deadline of January 16,” says Donna Powers, the director of communications for the District of West Vancouver.

She says the district is looking for a creative solution that both preserves the cultural importance of the house, while still being fair to the owner. “We are looking at any legislative possibility to protect the house without devaluing the land. We value culture, and we need to be fair to the person who owns the land.”

“Additional density, a land swap—these are options. We do not have the authority to expropriate the house,” she adds.

Staples hopes the owner will be willing to sell. “We have cash-ready people who are willing to buy it, and we have done two appraisals on the property paid for by our Society to make sure we offer fair market value,” she says.

“We have also found people who have fixed up Ron Thom properties before and are prepared to participate,” she adds. “It’s in excellent shape. It was Ron’s favourite house.”

Another view of the Forrest residence, 1962. Photo by Selwyn Pullan/Courtesy of the West Vancouver Art Museum.

Ron Thom was born in Penticton in 1923 and studied painting after serving in the RCAF during World War II. He graduated from Vancouver School of Art (now known as Emily Carr University of Art and Design) in 1947. He did not have formal architectural training, but went on to become a registered architect and was eventually made partner before opening his own firm.

Thom was interested in architecture as a complete work of art, from the first inspiration to the execution of the smallest details. Many of his designs were celebrated and high-profile, such as Massey College, Trent University, and the Shaw Festival Theatre. He was made an Officer of the Order of Canada in 1980 for his contributions to architecture and design. He died in 1986.

Staples remains optimistic. “It’s not so much picking your battles, but it is about what you can save. Not everything can be. But these very, very, very significant ones should be saved. This is a masterpiece of architecture that is part of our culture.”

Explore more stories on architecture in our Design section.