A family home is—or should be—a memory garden of friendship, family, art, and comfort. Ron Thom, who lived and worked in the golden age of West Coast modernism, harnessed this directive with every client. Even after Thom moved away to Toronto and international fame for his architecture of Massey College Trent University and the Shaw Festival Theatre, his favourite design brief remained the family home. And one of his most cherished houses and clients, a Vancouver home for Morton and Irene Dodek, stands as a testament to his ethos.

In 1957, Morton Dodek was a young physician, a graduate of the first class of the University of British Columbia’s medical school. Irene was a researcher and tireless community advocate for the Jewish Museum & Archives of BC. They purchased a lot in Vancouver’s Oakridge neighbourhood, part of a great swath of land once owned by the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Morton and Irene drove around West Vancouver viewing a series of Ron Thom’s recent creations. Every house they wandered through astounded them—particularly the Carmichael House, a magnificent gem with built-in furniture and intricate woodwork with a gargantuan fireplace. As they drove back across the Lions Gate Bridge, Morton and Irene both felt their hearts pounding and their adrenaline racing. They had found their architect—a graduate of the local art school, not the architecture school, who created each house with the eye of an artist, as though he were crafting a huge, functional sculpture.

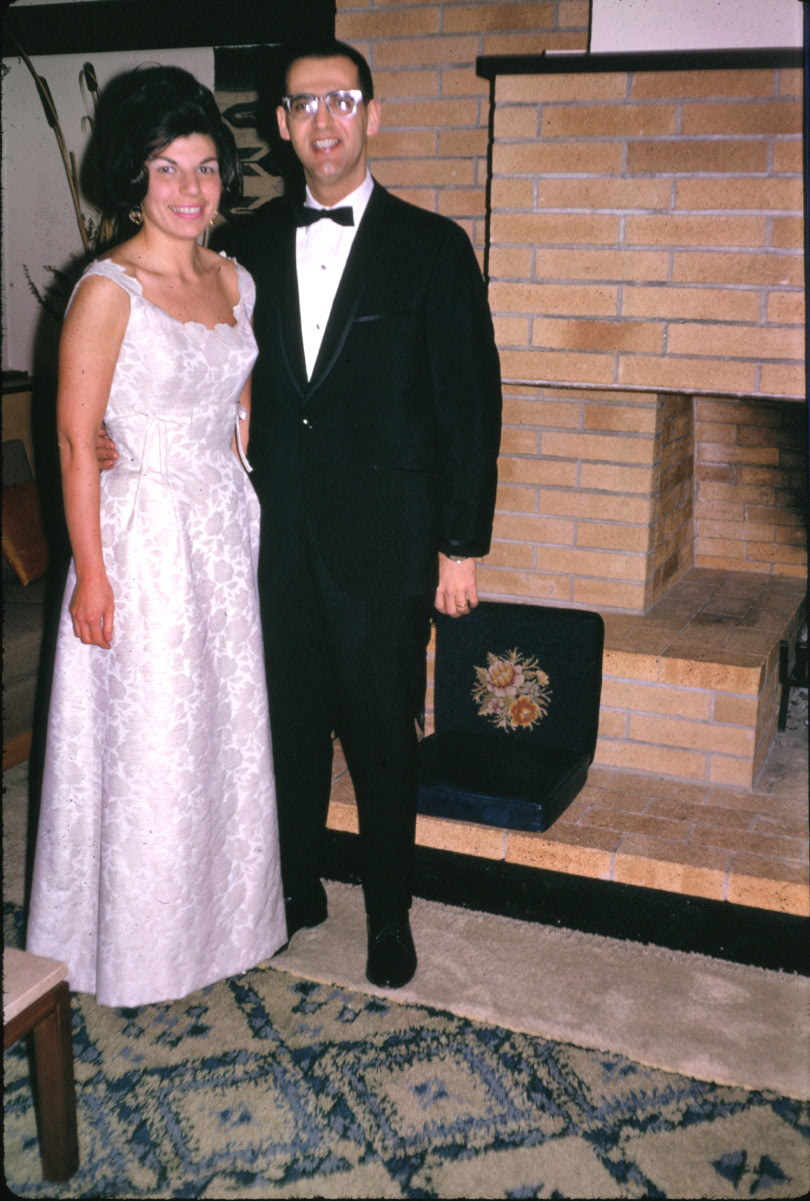

Irene and Morton Dodek posing in the family home. Photo courtesy of the Dodek family.

Thom first devised the Dodek House as a small L-shaped home anchored by a massive hearth, able to expand into a larger U-shaped structure as their finances and family grew. He used a conventional orthogonal grid, but with his characteristic inventive arrangement of space. The ceiling in the upper-floor master bedroom is vaulted and girded around its perimeter with wooden planks to create a version of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “tray ceiling.” The triangular prism of space created serves to visually break up the inert feeling of an ordinary rectangular room.

With its steeply pitched roofline, off-white plaster cladding, and deep eaves, the finished house evokes an exotic fusion of Japanese traditional and European medieval. The house went on to earn a Massey Medal for Thom and was featured prominently in a 1961 exhibition of his work at the Vancouver Art Gallery. The critical mass of attention from these late-1950s houses entrenched his reputation as the best architect in town, and therefore one of the best architects in the country.

As with many of his other custom homes, Thom also incorporated Wright’s “cavern and cave” concept, beginning with the unusually low ceiling in the entrance hallway, which segued into the adjacent overheight living room. This shift in ceiling height makes the initial entrance warm and reassuring, and then generates a sense of vitality in the house felt by the inhabitant moving through the higher spaces.

The bureaucrats at Vancouver City Hall didn’t much care for design theory, though. In December 1958, as the house neared completion, a city inspector brought over a stop-work order, because the foyer’s ceiling height was lower than the building code allowed. Morton headed to city hall and argued for an exception, on the grounds that the high ceiling in the adjacent living room more than compensated for the foyer’s low ceiling.

The Dodeks applied for the variance, and in an astute followup, Morton also sent the inspector a bottle of good scotch. Not a bribe, he emphasized, just a Christmas present. “You can give us a good Christmas present by just taking off that [stop-work] sign,” he suggested. The inspector agreed to the variance.

Morton and Irene went on to raise three children in the house: Peter, Gail, and Carla. Through a series of repeated visits, tweaks, and additions to the house, the family and the architect became cherished lifelong friends. “He exuded such warmth and curiosity and affection towards my parents,” Peter Dodek recalls.

Courtesy of the Vancouver Art Gallery Library and Archives.

Aside from his usual ambition of designing a structure as a work of art, Thom designed the house first and foremost as an intimate place for raising and nurturing a young family. “Our parents told me that Ron made our bedrooms small because he felt that we should be together in the family room.”

The home has also served as a memorable gathering spot for friends, neighbours, and colleagues, with the Dodeks’ earliest guests marvelling at what was then a radical house design, with its vaulted ceiling and exposed beams. The Dodek progeny remember crouching in the stairwell and watching the action. After some neighbours remarked to Morton and Irene how late the children were staying up, the Dodek parents asked their friend the architect to create some privacy for that stairwell window. His solution: a stunning pane of artfully coloured fibreglass devised from flattened industrial egg crates, evoking the look and magic of stained glass.

Courtesy of Penny Mitchell.

As with most of his designs, Thom anchored the house with a massive hearth, which he treated as the essential nucleus of a family home, the gathering spot projecting literal warmth and fostering connection. At every stage of life, the parents or entire family would pose in front of the fireplace: Peter’s bar mitsvah, graduations from high school, engagement photographs, shivas.

When Irene passed away in 2019, Morton remained in the house, consoled by its comforts and beauty. “The entire process of working with Ron and building their dream home was pivotal and one of their biggest sources of pleasure and pride,” Carla Dodek says. “They made a pact with each other that whoever was to survive would remain in the house,” she notes. “My dad found so much comfort in the house in spite of being left a widower. He commented daily how fortunate he was to be enveloped in the beauty of the architecture, especially during his last five years.”

Morton died last year, at 95, and their three now-grown children are in the wistful process of finding the house’s next stewards. The younger Dodeks have no need to fear the next occupants will alter or demolish the landmark home, since their parents voluntarily procured a heritage covenant to ensure its long-term survival.

“I really do think that living in a work of art has really affected my perspective on life,” Gail says. “When you grow up surrounded by beauty, you appreciate beauty in a more profound way.”