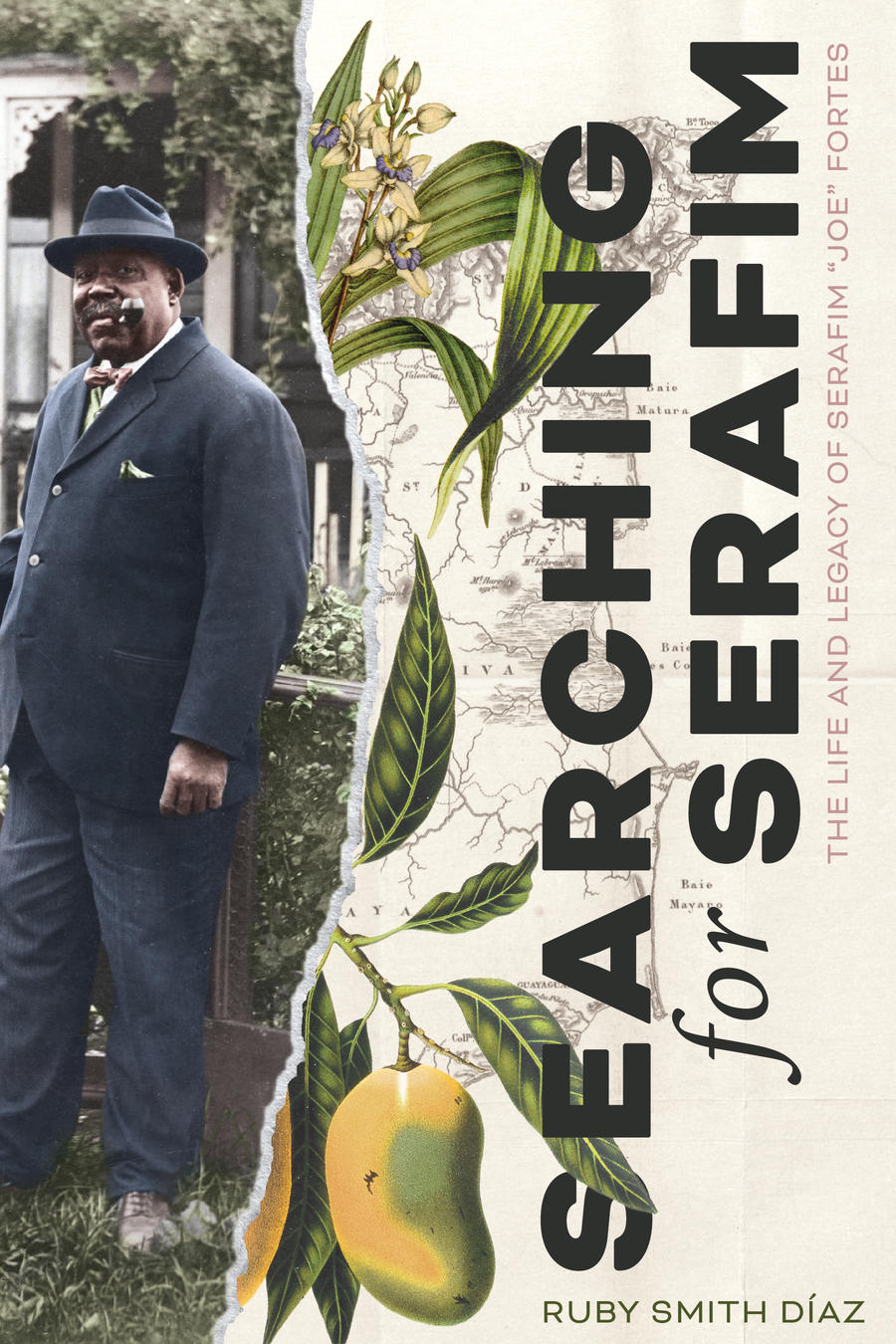

Ruby Smith Díaz is a multidisciplinary artist, educator, and award-winning body-positive personal trainer. Her first book, Searching for Serafim, explores the life and legacy of Serafim “Joe” Fortes, a beloved Black hero of Canadian history. It was released January 28 by Arsenal Pulp Press. Here, more than a century after his death, she reflects on her own experience as a Black person living in B.C.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Serafim’s hands these days,

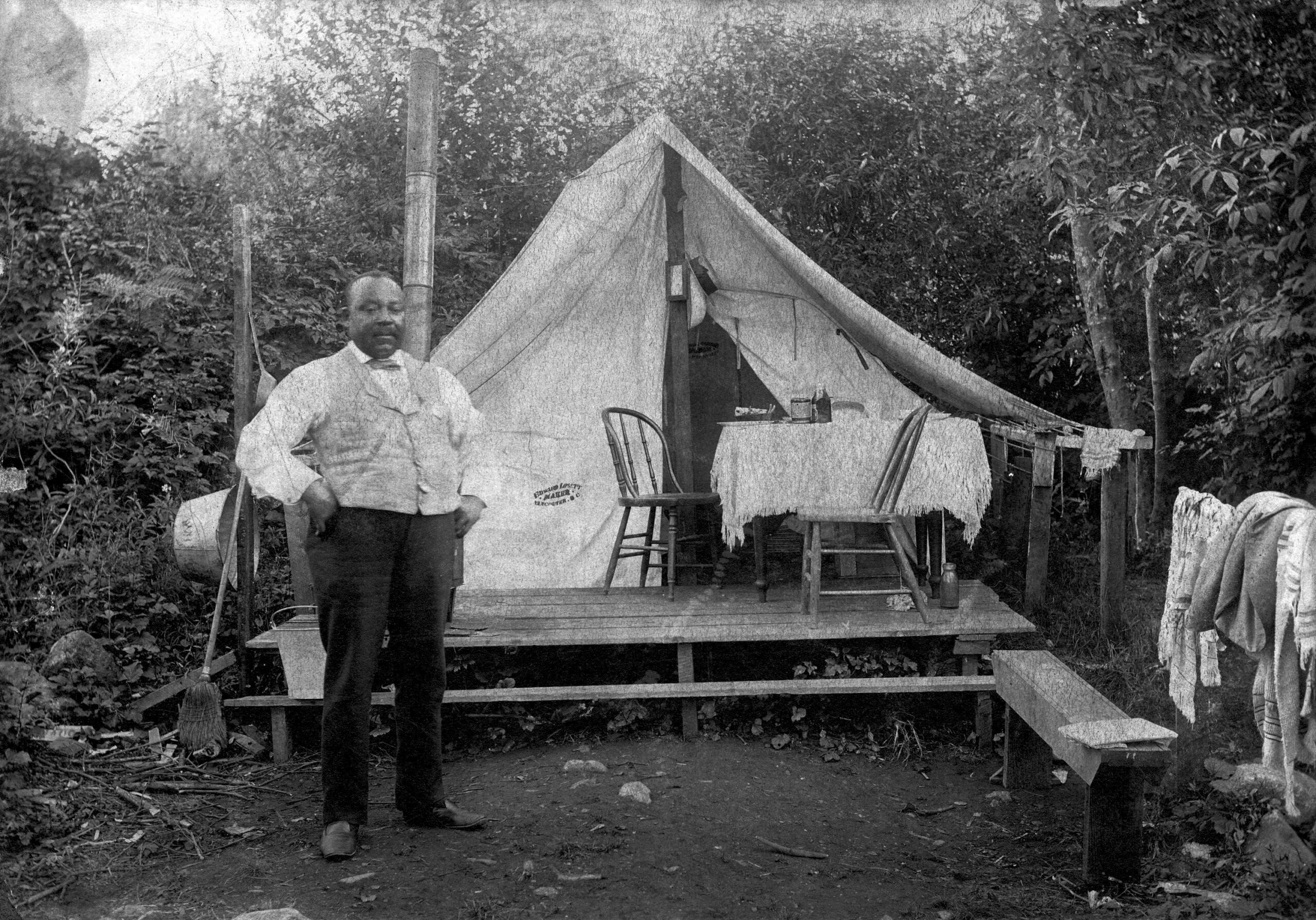

and how Serafim “Joe” Fortes’s hands, originally from the island of Trinidad, helped save over 100 people from drowning, leading him to became one of Vancouver’s most beloved heroes.

Hues of beautiful mahogany, always perfectly poised above azure ocean waves on the shores of Í7iy̓el̓shn (English Bay beach), as he taught white Vancouverites how to swim,

so graceful, so strong, and so acutely aware of every single one of his body’s movements in the water and on land.

I’ve been thinking a lot about how his hands are a lot like mine,

a similar shade of mahogany,

and how the both of us,

over 100 years apart,

in the same place,

have perfected the art

of always having our hands in view in public space.

Even after moving away from Vancouver,

I make sure not to carry a purse that’s too big,

or too cheap looking,

and at every store entrance I pause to make sure

that my purse is perfectly poised beside my body,

not too open, not too far

or too close by my side,

nowhere near the red shopping basket I pick up,

and that my beautiful mahogany hands

are always always always in view.

Searching for Seraphim: The Life and Legacy of Serafim “Joe” Fortes is now available from Arsenal Pulp Press.

As I navigate the other patrons through the store aisles, I think about how

Serafim navigated white supremacy on English Bay

and Greater Vancouver

at a time when city councillors were actively campaigning on the “stand for a white Canada platform” and when the Anti-Asian Exclusion League was quickly gaining momentum in the city.

I think about how at any given moment, he could easily be found as “a large-sized chocolate drop with red stripes around it bobbing up and down in the water.”

Easily found if you are always being watched.

Easily found if you are the only one of a darker complexion

permitted to be in a public space

amid a sea of lighter skin.

Easily found,

like I seem to be

down every aisle,

in every grocery store I enter.

I just wanna buy fruit and some detergent, frozen spinach, toothpaste, and maybe a nice birthday card for my mom, goddamnit.

But it seems that in every store I go into, there are men who also want to buy fruit and some detergent, frozen spinach and toothpaste, and maybe a nice birthday card for their mom goddamnit, at the exact same time as me.

It seems like an awful big coincidence to me. Or too big of one.

As I carefully place the items I need in my basket, I think about how I have just written a book that takes place over 100 years ago that speaks to Black experience in B.C. and how horrified I am at Serafim’s treatment—celebrity by day, yet unpaid for his services for years. I think about how maybe going shopping for food, like I am today, wasn’t so easy for him during those years.

I think about how to this very day, Black and Indigenous communities rank first for having the lowest socioeconomic status in this country and the highest child poverty rates, and I find myself horrified all over again at how little has changed since his death in 1922.

I walk over to the next aisle, busy with shoppers, and think about how the streets of Vancouver were filled as residents paid their last respects to him, and how politicians made sure to say at his service that “it was never said to his disadvantage that this is a white man’s country.”

I pause at the end of the aisle to glance over my grocery list one last time, hoping that something like that will never be said at my funeral, and notice the man who has also been shopping for fruit and some detergent, frozen spinach and toothpaste, and maybe a nice birthday card for his mom has also paused at the end of the aisle and is looking at me through his periphery. Maybe he forgot his list at home.

As I stand in line at the checkout, I remember how at home, interview requests are stacking up for my book. I remember how I am told that my work on recovering Serafim’s life from the whitewashed archives is invaluable, and how devastatingly beautiful it is that I’ve woven my own story alongside his.

Ruby and Serafim standing side by side at Íy̓el̓shn, one century apart. | Digital collage by Ruby Smith Díaz using image of the author by Keith William Miller, as well as a photo of Serafim Fortes from the City of Vancouver Archives.

As the cashier scans my items under the careful supervision of the man with the empty basket behind me, I think about how the workshops on equity, inclusion, and diversity I once led were incredibly high in demand, but there’s no way that this guy with the empty basket knows that, because clearly he hasn’t taken one of my workshops. Maybe he would if he knew who I was. But probably not.

I carefully pull my purse onto the counter, ensuring that the cashier and the man behind me with the empty basket who wanted some detergent, frozen spinach and toothpaste, and maybe a nice birthday card for his mom can see that

MY HANDS WILL GO INTO MY PURSE ONLY TO RETRIEVE MY WALLET AND NOTHING ELSE.

I wait for the transaction to go through, and in the meantime, the radio over the store loudspeaker blasts how people like me are stealing jobs, driving crime, raising the cost of rent, entering the country illegally, eating dogs and cats, defiling women and

I swear the dial must be broke because—

isn’t this a transmission from 1907?

I just saw the B.C. newspapers in the archives with these same headlines when I was researching Serafim’s life over a century ago. I just read about the “dusky peril”

and “those people from over there” “threatening the purity” of this nation and our women and our economy.

I guess I never realized how high in demand underpaid jobs in fields of blueberries under blazing sun, or as live-in caregivers with no breaks, or scrubbing the toilets in malls at two in the morning were to Canadians.

Serafim and I—our beautiful mahogany hands—aren’t so different.

And in many ways, I don’t find that comforting.

I walk out of the store, groceries in hand, and go home to write,

to try to make sense of it all somehow.

And when it doesn’t—and often it doesn’t—I look through my telescope and try to sight the moon,

or any stars,

somewhere

in a distant universe

where things make a little bit more sense, maybe,

than they do here.

Read more essays.