When John Baker died at a great age in 1871, just four years after Confederation, he was hailed as a war hero. Today, he is remembered as likely the last surviving person to have been born into slavery in Canada.

Baker fought with the 104th Regiment during the War of 1812. He took part in the failed raid on an American naval squadron at Sackets Harbor, New York, and was later wounded during the bloody Battle of Lundy’s Lane, holding off American invaders on a narrow, dusty road in what is now part of the city of Niagara Falls, Ontario.

Baker was proud of his battle medals and wore them whenever dignitaries visited or a parade was held near his home in Cornwall, Ontario. He was born in Quebec in 1779 to Dorinda, an enslaved Black woman, and Jacob Baker, a free white Hessian soldier. Dorinda was the granddaughter of a man known as Cato Prime, an African who had been captured and enslaved in Guinea.

Because his mother was a slave, so too was John Baker, according to the laws of the time. Both were owned by Colonel James Gray, a kilt-wearing officer with the 42nd (Black Watch) Regiment. Dorinda, or Dorine, as she was also known, had been a gift to the colonel’s bride.

Just three years before Baker’s death, the historian J.F. Pringle interviewed the old man, describing him as “a very dark mulatto of amiable disposition and countenance, hobbling from rheumatism and laying down his wood-saw as I asked him to sit down on a box in a grocery, and handed him a plug of his favorite weed.”

“The Colonel had much property,” Baker told him. “He was strict and sharp, made us wear deerskin shirts and deerskin jackets, and gave us many a flogging. At these times he would pull off my jacket, and the rawhide would fly around my shoulders very fast.”

The history of slavery in Canada has been mostly overshadowed by the story of this land being a haven for escaped African American slaves who sought refuge along the Underground Railroad. The network of secret routes and safe houses ended in what is now Ontario and became well known to generations of children through the anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The character Tom was loosely based on the life of Josiah Henson, who had found sanctuary near what is now Dresden, Ontario. Henson’s old homestead is now the Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site, an open-air museum.

Upper Canada became a refuge in 1793 when Lieutenant-Governor John Graves Simcoe approved legislation prohibiting the importation of slaves to the colony. But Simcoe’s act did not free slaves already living in Canada. When it came to freeing slaves, the British parliament could not bring itself to simply end a great crime.

Not until the summer of 1833, after decades of abolitionist campaigning and in the wake of a bloody uprising known as the Baptist War or the Great Jamaican Slave Revolt, did the British parliament pass the Slavery Abolition Act. With royal assent given by William IV, who was Queen Victoria’s uncle and predecessor on the throne, the act freed more than 800,000 enslaved Africans in South Africa and the British Caribbean.

The act, which took effect on August 1, 1834, also freed about four dozen slaves in the Canadian colonies, according to historian Natasha L. Henry.

Painting of a Black Canadian woman by Caroline Bucknall Estcourt, 1838/Library and Archives Canada.

The Toronto Globe and other Ontario newspapers described Emancipation Day at the time as a celebration of the liberation of slaves in the British West Indies, usually ignoring the enslaved people in the Canadian colonies. After its founding in 1844, the Globe’s publisher, George Brown, used the pages of his newspaper to promote emancipation in the United States, though he was also accused of hypocrisy for refusing to employ a Black printer.

More than three decades passed before American slaves were liberated at the end of the bloody Civil War south of the border. Union soldiers arrived in Galveston, Texas, with news of emancipation and the end of the war on June 19, 1865, about 30 months after President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. The June 19 date has been marked ever since as Juneteenth, a celebration given greater prominence in recent years thanks to the Black Lives Matter movement.

In 2008, the province of Ontario proclaimed August 1 to be celebrated every year as Emancipation Day. Toronto’s Caribbean Carnival (formerly Caribana) normally culminates in a parade on the first Monday in August and is part of Emancipation Day activities. Wanda Bernard, a senator from Nova Scotia, introduced a bill last year calling for federal recognition of Emancipation Day, as well. It had a second reading but died on the order papers with last fall’s election. British Columbia, which did not have a permanent British settlement until nine years after the Slavery Abolition Act came into effect, does not officially recognize the day.

Even without formal recognition, the day has been celebrated by Black Canadians and their allies for nearly two centuries.

In the late 1850s, Toronto, which counted a population approaching 45,000, was home to about a thousand Black residents. Many lived in a neighbourhood known as St. John’s Ward, now downtown Toronto, a home to successive waves of immigrants, including refugees from the Irish potato famine and the European revolutions of 1848, as well as those who fled captivity in America along the Underground Railroad.

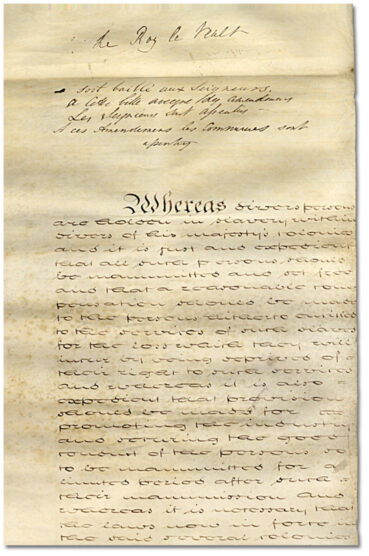

1833 British Imperial Act that brought an end to slavery in the British empire, courtesy of Parliamentary Archives, U.K.

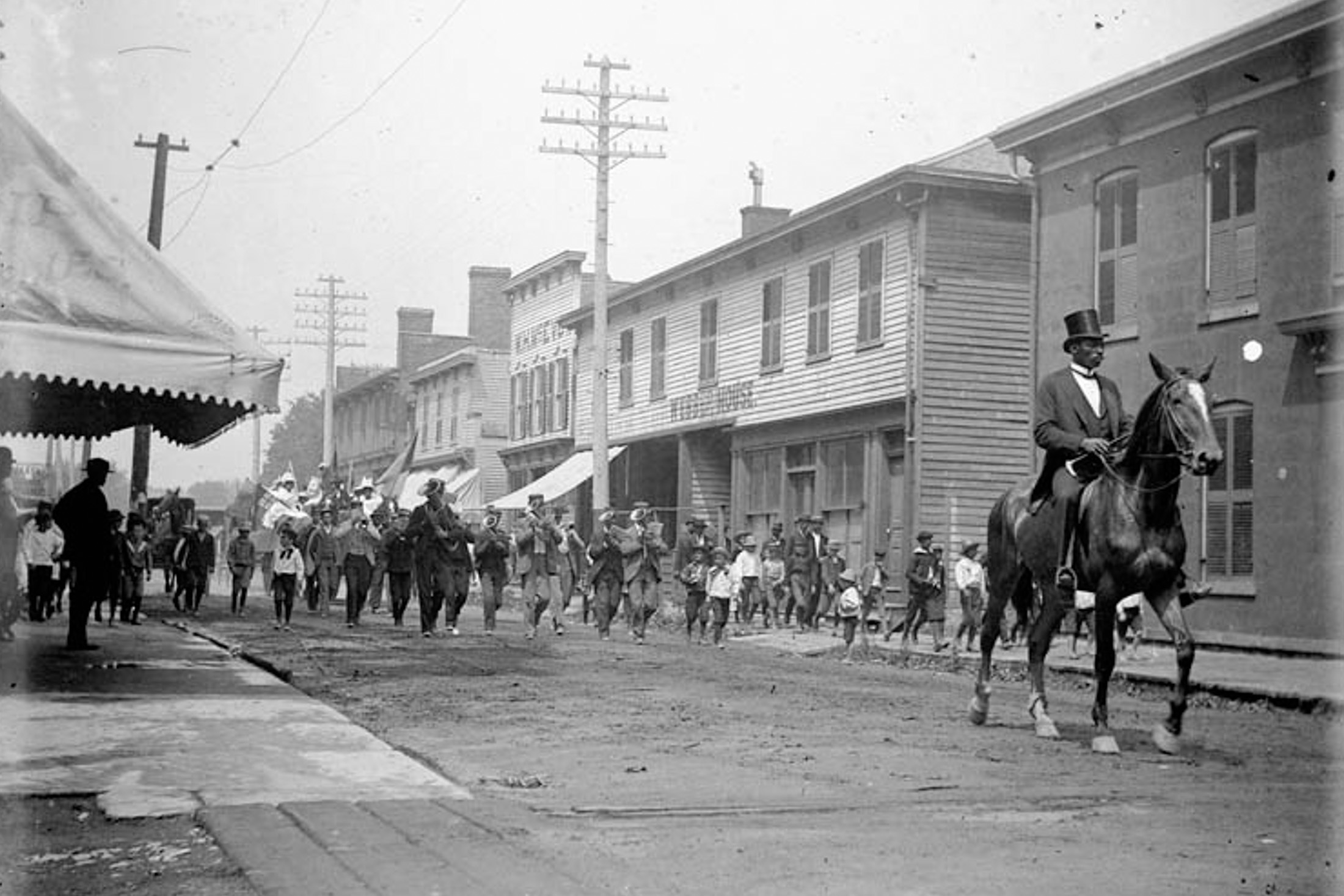

On August 1, 1858, the city’s Black community gathered at 6 a.m. at a church to pray for the abolition of slavery throughout the world. They then marched behind a band while carrying flags and banners to St. James Cathedral, where another service was held. After prayers, Reverend Canon Edmund Baldwin preached for an end to slavery in the United States.

“The rev. gentleman,” the Globe reported, “was listened to throughout with the utmost attention.” This was followed by a parade to the university grounds for a picnic and further speeches, including one by Reverend William M. Mitchell, which the newspaper noted “concluded by alluding to the pleasing fact that the moment the foot of the poor slave touched British soil he immediately became free.”

Similar events were held in other Ontario towns with Black settlements. Owen Sound, north of Toronto, claims to hold the oldest consecutive celebration of Emancipation Day, having held a picnic and now a festival every year since 1862. A Black History Cairn in the city’s Harrison Park includes broken shackles as a symbol of liberation from oppression and tyranny.

Even as the abolition of slavery is celebrated, it is worth noting the act’s limitations. The formal name of the legislation was a mouthful even for the 19th century: “An Act for the Abolition of Slavery throughout the British Colonies; for promoting the Industry of the manumitted Slaves; and for compensating the Persons hitherto entitled to the Services of such Slaves.” Instead of punishing slave owners, they were rewarded for having owned humans. The act created a fund of 20 million pounds sterling (more than $2 billion today), which was financed by a bank loan not retired until, believe it or not, just five years ago.

The act also failed to immediately release the enslaved. Instead, former slaves over the age of six were to be retained as unpaid apprentices for up to six years afterwards (later shortened after protests to four years).

In the meantime, those who owned slaves were neither pilloried nor punished. Many were honoured, and the names of Canadian slaveowners dot the landscape, including Jarvis Street in Toronto, named for Samuel Peters Jarvis, the scion of a louche, slave-owning family that owned six humans and lobbied for extending slavery even in the face of an abolitionist public sentiment.

The patrician Jarvis, born to wealth, and John Baker, born a slave, shared one experience—both were veterans of the Battle for Lundy’s Lane.

Baker did not have to wait until 1834 to be freed. After the colonel’s death, he became a personal servant of the son, Robert Isaac Dey Gray, a lawyer who drowned in 1804 when the schooner Speedy sank during a snowstorm on Lake Ontario. By his will, Gray freed Dorinda and John, as well as his older brother, Simon. The brothers each got £50 and 200 acres of Gray’s holdings of 12,000 acres of land.

Read more Community stories.