Sometimes I sound like an old-timer from the old country. “Which village are you from?” I find myself asking Karen Tam, guest curator of Whose Chinatown at North Vancouver’s Griffin Art Projects.

The exhibition features contemporary and historical photos, artworks, archival artifacts, and a board game designed by an architect, all focused on the Chinatowns of North America with an obvious focus on Canada. At the start of our conversation, I discover Tam is from Montreal. So am I.

Her parents came over from Hong Kong in 1967. My mother came over in 1964. Where did her father work? At the iconic Montreal restaurant, Ruby Foo’s. Mine did too.

Without meaning to, Tam and I trace the lines and connections between us, all of which lead to Chinatown. Not just Montreal’s or Vancouver’s Chinatown, but all of them.

Xam Yu Seafood Restaurant, Toronto, by Morris Lum.

Talk of villages is fine, but in truth I can never find the places my family came from on Google maps. The imposition of Mandarin upon Cantonese place names has made it impossible, as I don’t know how to read Chinese characters, to figure out what is where. And even if I could, there’s a good chance urban development has wiped them completely off the face of the Earth.

Like my great-grandparents and grandparents, China ceased for me to be a homeland. Chinatown, a place where Chinese people were often confined but also found refuge—be it in San Francisco, Paris, Montreal or Vancouver—became and remains it.

Tam agrees. Upon arriving in a new city, she will visit the Chinese district “to feel like ‘Okay, I’m in my comfort zone.’”

Which is odd because they are unreal and unstable places. Chinatowns can feel like sets built for the cameras of tourists, swappable from city to city. And, like a set, Chinatowns are always under threat of being torn down.

Lee’s Community Association of Edmonton, by Morris Lum.

Tam points out a photograph by Montreal’s Suzanne Girard, La Pagode et le Complexe Guy-Favreau en construction. Taken in 1981, it shows on the right a pagoda. Was it an expression of culture or faith, or simply a landmark? On the left are the concrete columns and beams of the block-long Guy-Favreau Complex, then under construction. Like the Georgia Street and Dunsmuir viaducts in Vancouver, the harbinger of development threatened Montreal’s Chinatown.

I vaguely remember the pagoda sat across from the Lee’s Association of Montreal where my ah yeh (paternal grandfather) lived. I used to visit him every Sunday as a child. I would climb to the floor where all the old men lived. In my ah yeh’s cubby, the walls were covered by calendars, calligraphy scrolls, and pictures of family I still do not know. I’d sit on his bed. He would pat my hand, ask me questions which I tried to answer in broken Cantonese.

He would press some cash, even a C-note, into my palm. Which was incredible, but even more incredible to me was the hit he would take from a bamboo bong that sat in a bamboo bucket filled with water. What he smoked remains a mystery but I can still hear the strange gurgling sound it made.

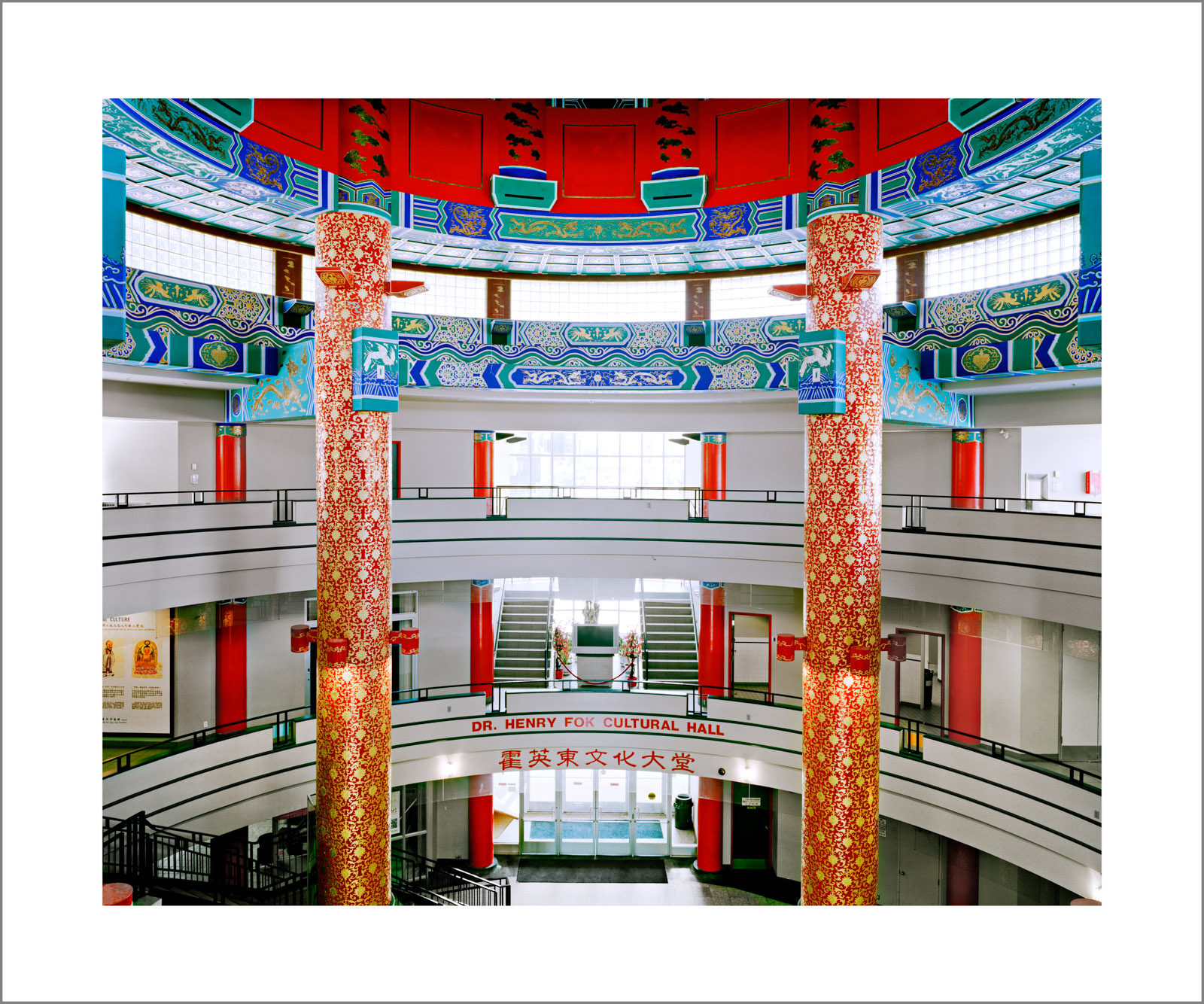

Chinese Cultural Centre, Calgary, by Morris Lum.

Today, my mother lives a few blocks from where my grandfather once lived.

As a Chinese-Canadian, I am baffled by how exotic Chinatown can feel even to me— even as it feels like home to me.

There are two places in this world I’ve always thought I would end up. The ultimate, and morbid, destination would be Mount Royal Cemetery in Montreal. Three generations of Lees already lie in its Chinese section (Chinatown of the dead, you could say). A thin curtain of white birch and northern ash does its best to shelter their tombstones from the wind. If there are any places on this earth I could claim, this is one of them.

But before that, I see my future self making a stop in Vancouver’s Chinatown. Old Man Lee (coming soon) in a grey suit that has grown bigger as he has grown smaller. Upon his head sits a battered fedora cocked just so, and, of course, he wears a jaunty bow tie knotted with an asymmetric dash of je ne sais quoi.

And if you’re a tourist? You’ll find him in the booths on the right side of New Town Bakery on Pender Street where the vinyl benches are orange, the coffee comes with condensed milk, and the bak tong gou, sweet fermented steamed rice flour cake, tastes just like his grandparents made it.

Go ahead take his picture. He’ll be the local colour. It’s good to be the denizen of someplace. It’s good to be home.

Read more Essays.