When I was five, my family left Vancouver, and an imbalanced narrative of food and culture began. My mother’s family was now more than an hour away, and my father was the only driver. He often wouldn’t be home for dinner, but the effect of the move (we were a walk away from his parents now) could still be felt: my mother’s cooking routines, as a Vietnamese-born Chinese-Canadian immigrant, were disrupted. Her improvisations went against the current of what the suburbs could provide, not just on its supermarket shelves, but the absence—away from her family in the city—of a lively, communal kitchen. My sisters and I would hear instead stops and starts, my mom thinking out loud, trying out whatever was in the fridge (my dad did the shopping, too), searching for fragrances; trial and error. Against the comparisons of Chinese take-out (always the same) and, when he’d cook, my dad’s family recipe cards (always with a nostalgic story, his British-Ukrainian family having lived in Canada for generations) my mother’s cooking could seem full of lacunae and half-erased memories.

Over time, I started to gain an appreciation for what was going on—I learned the difference between egg rolls and birthday misua served with egg. But, though I came at it from a different angle, I ended up with the dominant attitude most share: there’s authentic Chinese food, underappreciated, and chop suey Chinese, popular with people who don’t know any better.

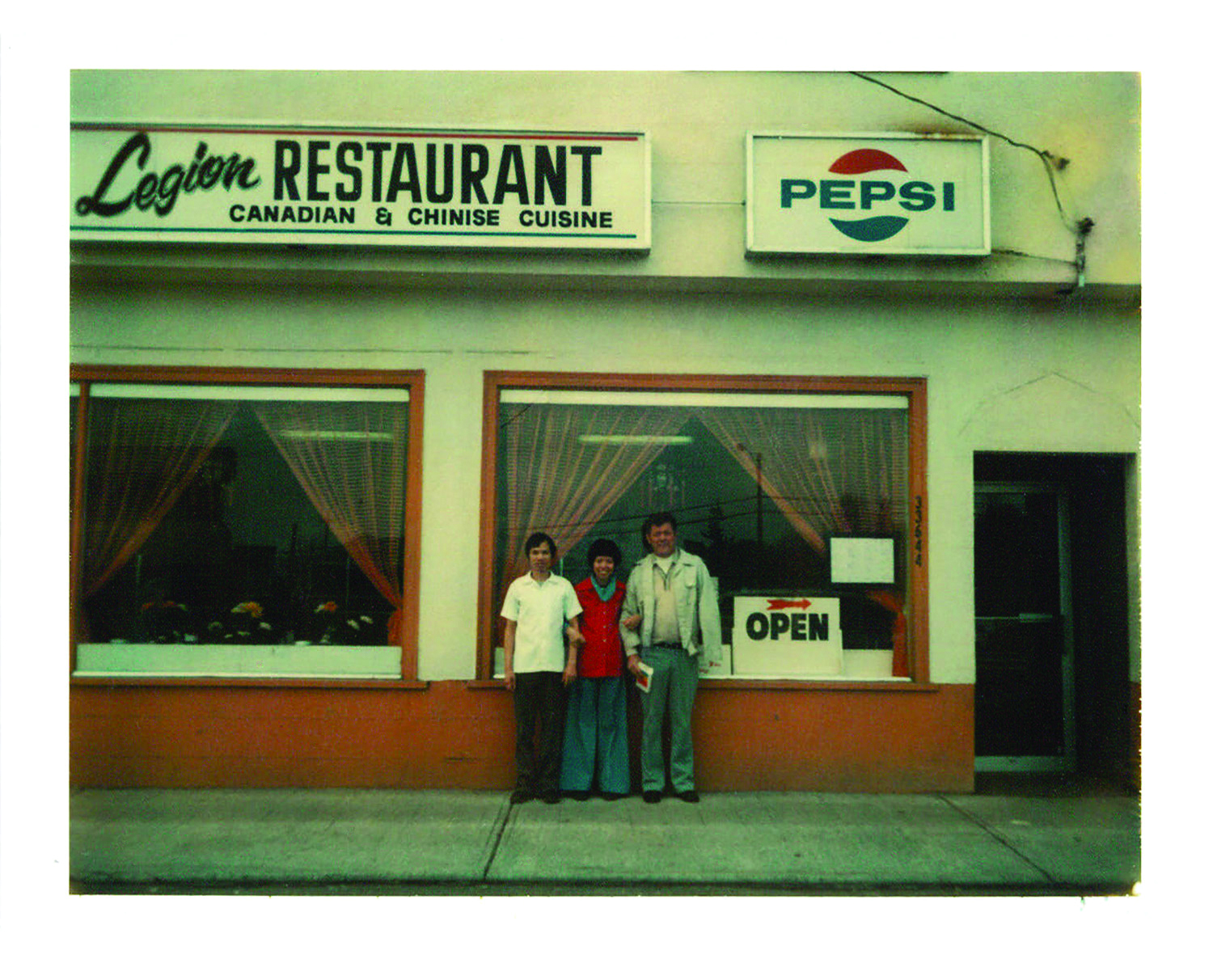

Ann Hui, The Globe and Mail’s national food reporter for the past decade, wanted to do something about that split. Pitting the cuisines of Chinese-Canadians against each other, both long-running traditions by now, just didn’t seem like a satisfying end of an argument—there had to be a better story there. So she crossed the country, wrote a two-part feature for the paper, and the reader response was large enough that it led to a book, Chop Suey Nation: The Legion Cafe and Other Stories from Canada’s Chinese Restaurants. Published earlier this year, it expands the road-trip account, and adds Hui’s own story in greater detail.

“It did not come naturally to me at all,” Hui says over the phone, having just finished a visit at the Sunshine Coast Festival of the Written Arts. “As journalists, our instinct is to keep ourselves out of the story as much as possible… It felt weird to be talking about myself in the first person, it still feels weird.”

The memoir half of the book begins in Hui’s parents’ house in Burnaby and spreads outward—it’s as carefully researched and vibrantly captured as the stories collected in the original article, but it’s the tougher angle to take. Though social media has made first-person pitch-writers of us all, there’s still nothing more difficult to get right than your own story—to make it clear without flattening it, to give it depth without over-selling its significance.

In this case, it also could have upset the balance of what is otherwise an easy-to-explain story hook. But in fact, it gives Hui a more challenging, detailed example of what she found everywhere else in the country.

“In terms of something that focuses not just on the cuisine, but on all of these different ways that food intersects with culture and immigration and business and commerce, and all of these things that make these restaurants so fascinating, I don’t think anybody else has done it here [in Canada],” Hui says.

From the typical point of view, chop suey is inauthentic, chop suey panders to unrefined tastes, chop suey is cheap; chop suey is something that will hopefully become a relic of the past. The knot that Hui unties is this: to show how this Chinese cuisine was a compromise, an attempted match with European-Canadian customers—something to keep the lights on—but also to say this tradition isn’t irredeemable, or, to say that it should never have needed to be redeemed in the first place.

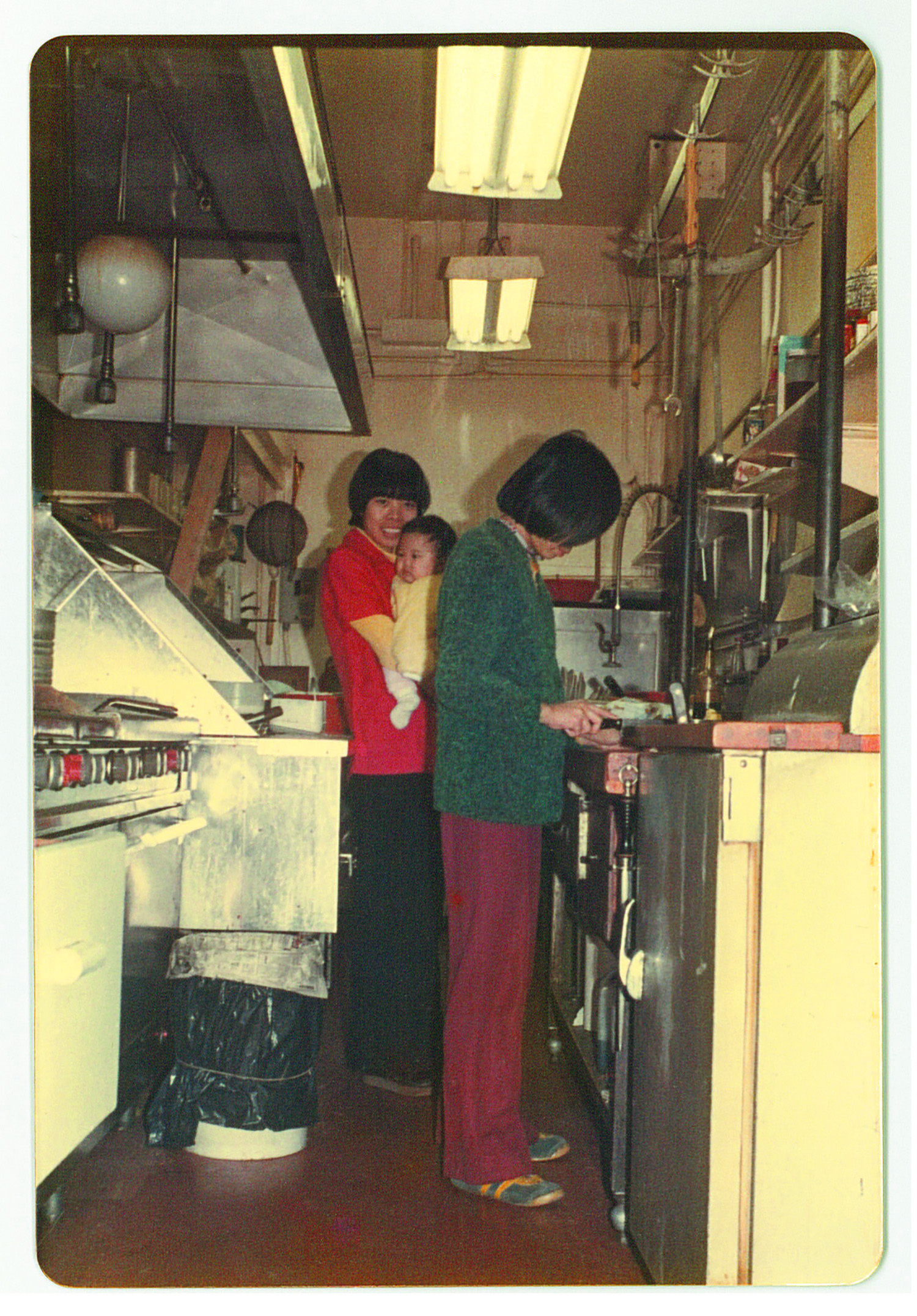

Hui calls it, in her book’s moment of crystallized realization, “A cuisine that was a testament to creativity, perseverance, and resourcefulness.” Like all commercial arts, the client puts a border around what’s possible, but they never really have a say about the flow of ideas in the workshop.

Vancouver is the epicentre of all this. The book opens with an excerpt from Chinatown’s obscured history: it was built, and then it was torn down, and this happened over and over. It wasn’t just the head tax. “Locals saw the cheap labour they provided as a threat,” Hui writes. “Others blamed the Chinese for what they claimed was an increase in crime and disease.” Every new immigration wave becomes a scapegoat. There were white supremacy marches; there were murders.

The restaurants across Canada then, are partly the result of Chinatown not being a safe place to stay. Go West, and then go anywhere else. But something survived here, too.

“Vancouver, for sure, is distinct from pretty much everywhere else I visited on the road trip,” Hui says. “Vancouver has had, for a long time, many, many, many generations and waves of immigration from different parts of China, and so the result has been this really rich number of communities that have developed here.”

This impacts the areas around Vancouver too: the Hui family’s temporary stay in Abbotsford is where some of the most striking details of restaurant life come out—boredom, panic, strange encounters, regulars, acceptance, and racism all together. As someone who grew up in Abbotsford (and my mother’s family traces back to the same area as Hui’s father), this was compelling for me in another, uncanny way, as Hui describes today’s partly-gentrified Abbotsford with equal parts curiosity and bewilderment.

But what she really focuses on is the excitement of seeing the place through her parents’ eyes.

“I’ve had their stories now living in my head for several years,” she says, speaking more broadly of the families she met throughout Canada. “And in some ways, I feel like they’ve all become a part of my life.”

Chop Suey Nation is an absorbing, eye-opening read for anyone, but it’s also a book for people who have had to make stir-fry sauce out of a ketchup base, for families that remember using celery, green peas, and broccoli in the days before the local store carried gai lan and bok choy every week. Hui’s parents put their restaurant days behind them the first chance they could, and only told their stories after decades of treating “fake” Chinese food with disdain. But what Hui’s book says, in effect, is no, this was worth something, too.

Chop Suey Nation: The Legion Cafe and Other Stories from Canada’s Chinese Restaurants is published by Douglas & MacIntyre. This story from our archives was first published Sep 5, 2019. Read more culinary insights here.