Only four blocks separate Sunrise Soya Foods’ Powell Street production facility from its original location. But that distance is also a lifetime for Peter Joe. The company’s CEO, Joe was born only a few years after his father launched a tofu empire in the back of their family-run grocery store in 1956.

“One early memory would be when my mom deep-fried fresh tofu,” Joe, now aged 60, tells me, when we meet at the Powell Street factory. “I would have it right away and add soy sauce. It was nice and hot and fresh.” He also remembers pulling tofu deliveries in a handcart from their Japantown location to customers in nearby Chinatown. Later, in the 1970s, when he had his licence, he would transport tofu across town to Lifestream Natural Foods on 4th Avenue, one of his first non-Asian clients.

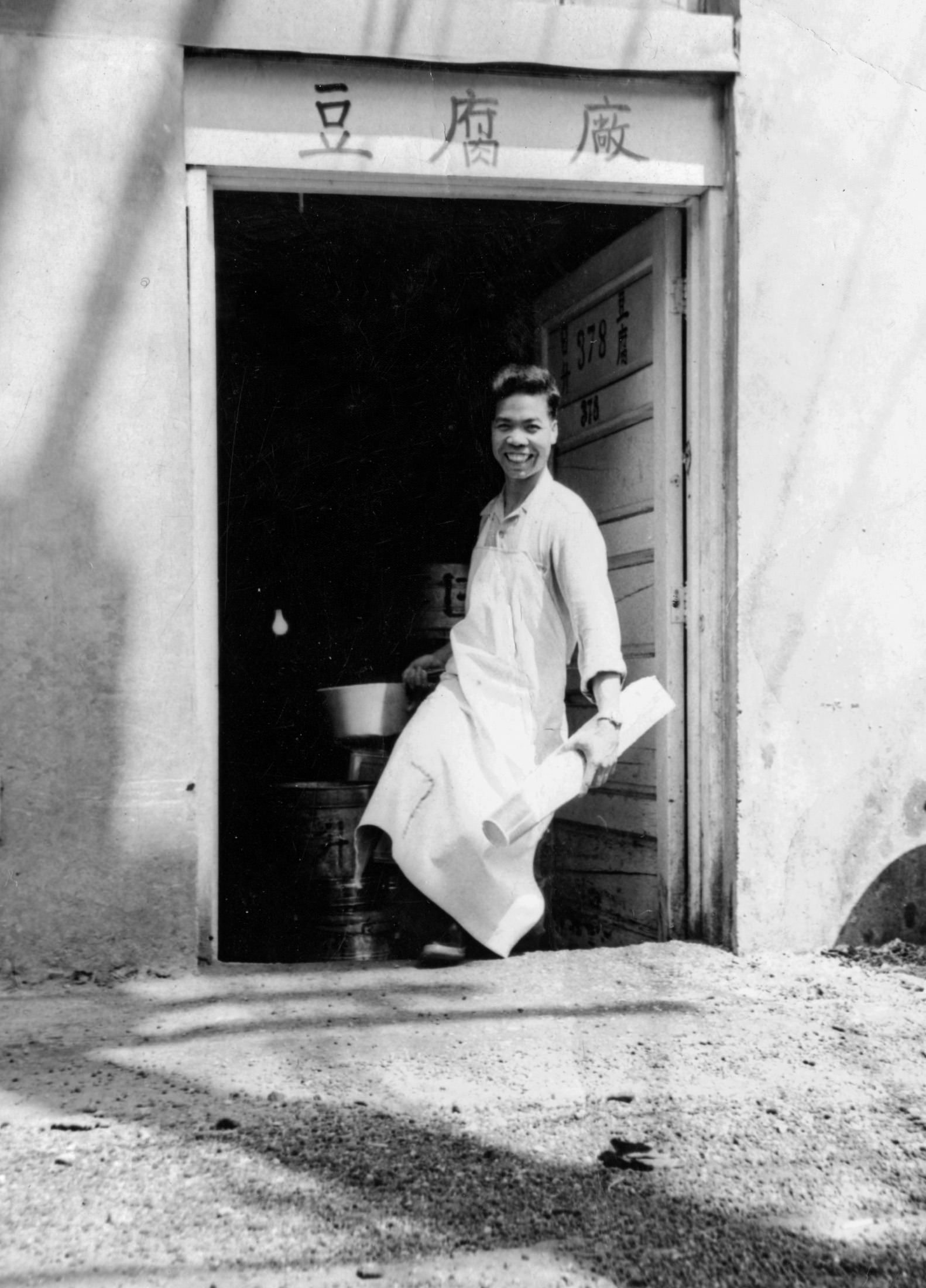

Leslie Joe started the Sunrise Market and its tofu business at 378 Powell Street in 1956. Photo courtesy of Sunrise Soya Foods.

Just when white people started eating tofu, I think to myself, was when I started rejecting it from my family dinner table.

Looking over a display of various Sunrise products in a factory display case, I realize how I’ve gone against a trend that has been Joe’s life’s work. Tofu has hit the mainstream. And Sunrise’s products are found in more than 1,500 stores in Canada. Once considered bland and hard to cook, the soy product is now lauded for its versatility, high protein, and relatively low carbon footprint.

One could make the case that Joe, who attended Strathcona Elementary and Britannia Secondary, is largely responsible for Canada’s tofu revolution. After he graduated from UBC’s Faculty of Commerce in 1983, he returned to the family business as it opened its first factory on Powell Street—a facility that forced the company to expand its customer and product range. Joe pushed for innovation.

Peter Joe making tofu in the 1970s. Photo courtesy of Sunrise Soya Foods.

Before this first factory, daily capacity was a “couple hundred pounds. Today each of our plants can make up to 15,000 pounds a day.” It’s here that soybeans from Quebec and Ontario are soaked, crushed, and cooked. Okara, the soy pulp, is then sieved from soy milk, which, in turn, is mixed with magnesium sulphate. Once it congeals and dries, it’s pressed into various moulds.

The machines in the facility come from Asia, where tofu preferences vary by country and sometimes within it. “The Taiwanese like pressed tofu,” Joe observes. “The Japanese like a softer tofu. In Hong Kong and southern China, it’s a smoother tofu, but in northern China, it’s firmer and harder. Koreans like it harder but softer for soups.”

Canadians prefer their tofu firm, presumably for the Tofu Frittata and Pulled Tofu and Apple Coleslaw Sliders that the Sunrise website provides recipes for. It’s these non-traditional adaptations that have allowed Sunrise to expand, opening other facilities in Toronto in 2002 and, last fall, in an 85,000-square-foot factory in Delta. In total, these factories employ more than 300 workers.

“It’s not a roller-coaster thing, it’s steady growth,” Joe notes, and yet, he adds neutrally, “the majority of Canadians”—non-Asians, I presume—“don’t know how to use it.”

Joe accepts my invitation to walk to Sunrise Market. Moving west along with traffic on the one-way street, he points out the Buddhist temple on the east end of Oppenheimer Park and the nearby Japanese language school. The park was the home field of the Asahi, the legendary Japanese-Canadian baseball team, and site of historic protests. Now it’s a village of tents. “In the ’70s and ’80s, the area had less of the homeless and social services,” Joe says about the neighbourhood’s shifting demographics, while careful to note that he’s never kept close tabs on this personally.

Peter Joe stands in front of his family’s Sunrise Market today.

There are other hints of the vibrancy of Japantown before the internment of Japanese-Canadians in the B.C. Interior in 1942. But they can only be faintly detected. Joe directs my attention to a mustard-coloured building on the north side of the street. Etched in art deco script are the words “T Maikawa,” the name of a department store founded in 1936 by a Japanese-Canadian businessman, Tomekichi Maikawa, who had previously made his fortune as a fisherman in Prince Rupert. According to the Changing Vancouver blog, the location is now a food-processing factory.

Yat Sang (“Sunrise” in Cantonese) Market, and its tofu business, operated at 378 Powell, Joe says, as we pass the address. A few years later, in 1961, it moved to its current corner location at 300 Powell, at Gore Avenue. (Before the Joes took over, the site was the home of Kawasaki Confectioner, which sold candied ginger and manju—a doughy treat with a sticky centre).

Nowadays Sunrise Market bustles with elderly Chinese ladies and aging hippies prodding through its “ready to eat” (cheap and ripe) fruit and produce. It was in the back of the market where fresh tofu was made and customers lined up to buy it.

Standing in front of a box of foam-netted Asian pears is Joe’s 84-year-old father, Leslie. (Peter Joe is his only son. Peter’s younger sisters, Sally, Winnie, and Jenny, run Sunrise Market, which once had Chinatown and Commercial Drive locations.) While his son wears a dry-cleaned blue dress shirt, Leslie keeps warm on a fall day with a Ryan Kesler–branded baseball cap and, in the manner of many Chinatown seniors, layers of activewear.

Our conversation is a mixture of (my) broken Cantonese and (his) simple English, with his son pitching in to translate. Leslie first started his business with his wife, Susan (who passed away in the 1990s), shortly after emigrating from southern China. In addition to Japanese businesses, he tells me, there was also a Chinese drugstore and society building. He points to a parking lot where a building once stood. “I lived there,” he says in English.

Leslie, who visits the store daily to chat with staff and suppliers, recalls how tofu provided protein when poverty meant that “Chinese people couldn’t even eat chicken eggs.” He adds in Cantonese, “Soya beans grow up easy. You can even drink it.”

“Do you remember when Westerners started eating it?” I ask him in Cantonese.

“Since Peter did a lot of advertising,” he answers in English.

Since when does a Chinese father revel pridefully in his kid, I wonder?

Back when I was growing up, tofu arrived on the dinner table steamed and topped with minced pork or scrambled in shrimp and peas. I always pushed it away, only occasionally accepting deep-fried tofu triangles from the Cantonese noodle house by my parents’ place.

It’s been my recent fascination with Asian dessert shops, the ones that sell bubble tea, fish-shaped waffles, and shaved ice on seemingly every other new city storefront, that’s brought me back to tofu. A few months ago, I ordered warm tofu pudding at one place and came to the realization that, in my quest to assimilate, I had turned my back on this silky sweetness.

The day after meeting the Joes, a craving leads me to another Asian market, where I buy the Sunrise soy milk and coagulant (agar-agar powder) necessary to make my own tofu pudding. As with all the dishes I first tasted from my mother’s kitchen, I turn not to her but Google for a recipe. Is the texture right? Is the ginger syrup thick enough?

I serve it to my stepson. When he doesn’t push it away, my hopes rise. If this dish conjures in him the kind of tofu nostalgia that Peter Joe described on Powell Street, I’ll have passed on something good.

This article from our archives was originally published in our Winter 2019 issue. Read more Community stories.