From a distance, it’s hard to imagine that the patch of grass perched on the edge of New Westminster’s Glenbrook Ravine Park ever served a sinister purpose.

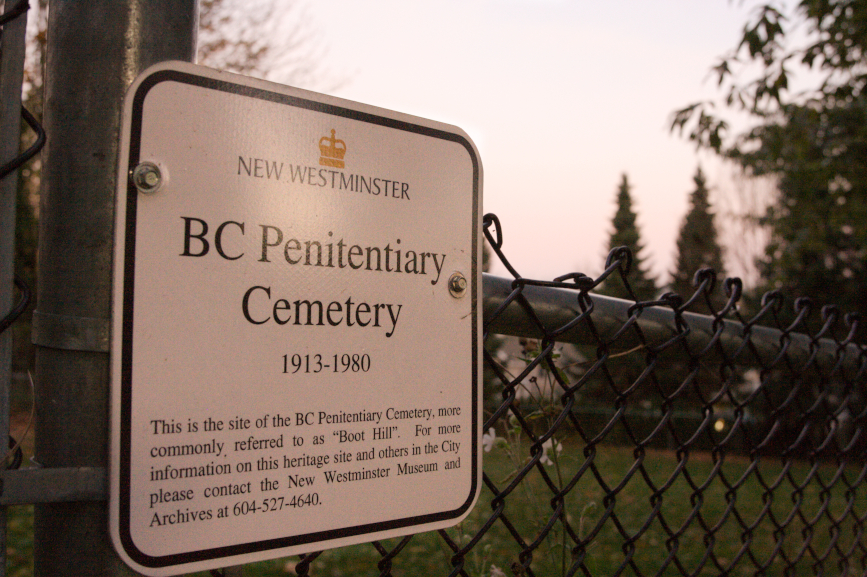

Tucked away behind a sprawling series of condominiums and seniors centres, and demarcated by nothing more than a simple metal fence with a small sign, it barely draws a second glance from the residents passing by, dogs or children in tow.

But for almost 70 years, it was known as “Boot Hill,” and served as the final resting place for at least 43 (or 47, or even up to 62, depending on who you ask) convicted felons—all of them inmates of the nearby, long-demolished, provincial penitentiary.

Some were murderers, some were child molesters, while others were petty thieves, thugs, or persecuted members of BC’s radical Doukhobor sect. Today, their bodies remain in the ground, some in unmarked graves, and the rest denoted by a simple stone marker—all of them devoid of any identifying information, aside from a prisoner number.

A simple stone marks Prisoner 1475’s grave. Photography by Jesse Donaldson.

Although Boot Hill likely welcomed its first bodies back in 1913, the nearby B.C. Penitentiary had already been in operation since the late 1870s, serving as the province’s first maximum security prison (built during the period when New Westminster was still the capital of B.C.). Prior to this, the land near the ravine had been designated as a public park, and the location of Government House.

“What a grand old Park this whole hill would make!” Colonel Richard Moody wrote to the governor in 1859. “I am reserving a very beautiful glen and adjoining ravine for the People and Park. I have already named it ‘Queen’s Ravine’ and trust you will approve.”

For a time, after the prison was first constructed, the park was still used for picnics and events, in full view of nearby prisoners, prompting the exasperated Federal Penitentiary Inspector to remark, in his 1879 report, that “it needs no argument to show how incongruous, how repugnant to good taste, leaving aside the incentive to breach of discipline and escape, it were (sic) to have games, music and dancing and other amusements, with all the attendant boisterous mirth, within easy earshot of convicts undergoing their allotted punishments.”

East wing and wall of B.C. Penitentiary in 1925. Photo from B.C. Penitentiary Collection.

Prior to Boot Hill, bodies (belonging to unfortunate inmates whose remains were never claimed) were either donated to medical schools, or interred in prison plots at the nearby Douglas Road Cemetery—a process that was both expensive and time-consuming, requiring crews of guarded prisoners to spend up to three days chopping through tangled layers of pine roots. And although the cemetery’s oldest headstone (that of one Gin O. Kim) dates back to 1914, its earliest recorded bodies—those of Joseph Smith and Herman Wilson—were buried in an unmarked grave sometime during the previous year.

Smith, a 24-year-old sailor with a short, stocky frame, had been serving a 10-year sentence for robbery and assault, after throwing ammonia in the face of a Main Street jewelry store owner back in 1911. Alongside Wilson, Smith had shot and killed a prison guard during an attempted jailbreak, one that the New Westminster British Columbian later called “one of the most skillful and dangerously near successful attempts at jail delivery that has ever been recorded.”

After successfully disarming three guards, the pair had been caught in a firefight near the exterior gate—one which left guard JH Joynson dead, and Wilson critically injured. Wilson later died of his injuries (after prison personnel denied him medical assistance for the bullet wound in his neck), and Smith was hanged in the yard on January 31, 1913, on the exact spot where Joynson had fallen.

“Although physically a midget of a man, he displayed the same fearless front and iron nerve that had characterized his whole career and more recently in his terrible attempt to escape from prison in which he killed his guard,” the British Columbian reported, “and later through the ordeal of his trial and while in solitary confinement, carrying them off with the spirit of bravado and reckless abandonment right up to the last minute he spent on earth.”

Smith was then, as the paper wrote, “placed in his last resting place in a far corner of the penitentiary grounds where the world will soon forget him.”

Of course, not every inmate interred at Boot Hill died in such spectacular fashion; many of the deaths at the penitentiary were due to poor prison conditions (tuberculosis was common), and suicide. In 1967, a petty criminal named Frank Wilson (denoted in the burial plot as Prisoner 1475) died of natural causes at the age of 72, after a lifelong career that included an impressive 45 different convictions.

Even when not serving as a burial ground, Boot Hill still made the newspapers on a number of occasions; because the work of burying bodies and carving headstones was left to prisoners, the remote site became a popular site for launching escape attempts. In March 1913, the British Columbian reported on a prisoner named Phillip Hopkins, who used his work detail as the opportunity to slip into the dense brush surrounding the prison graveyard (no word on whether Hopkins was recaptured).

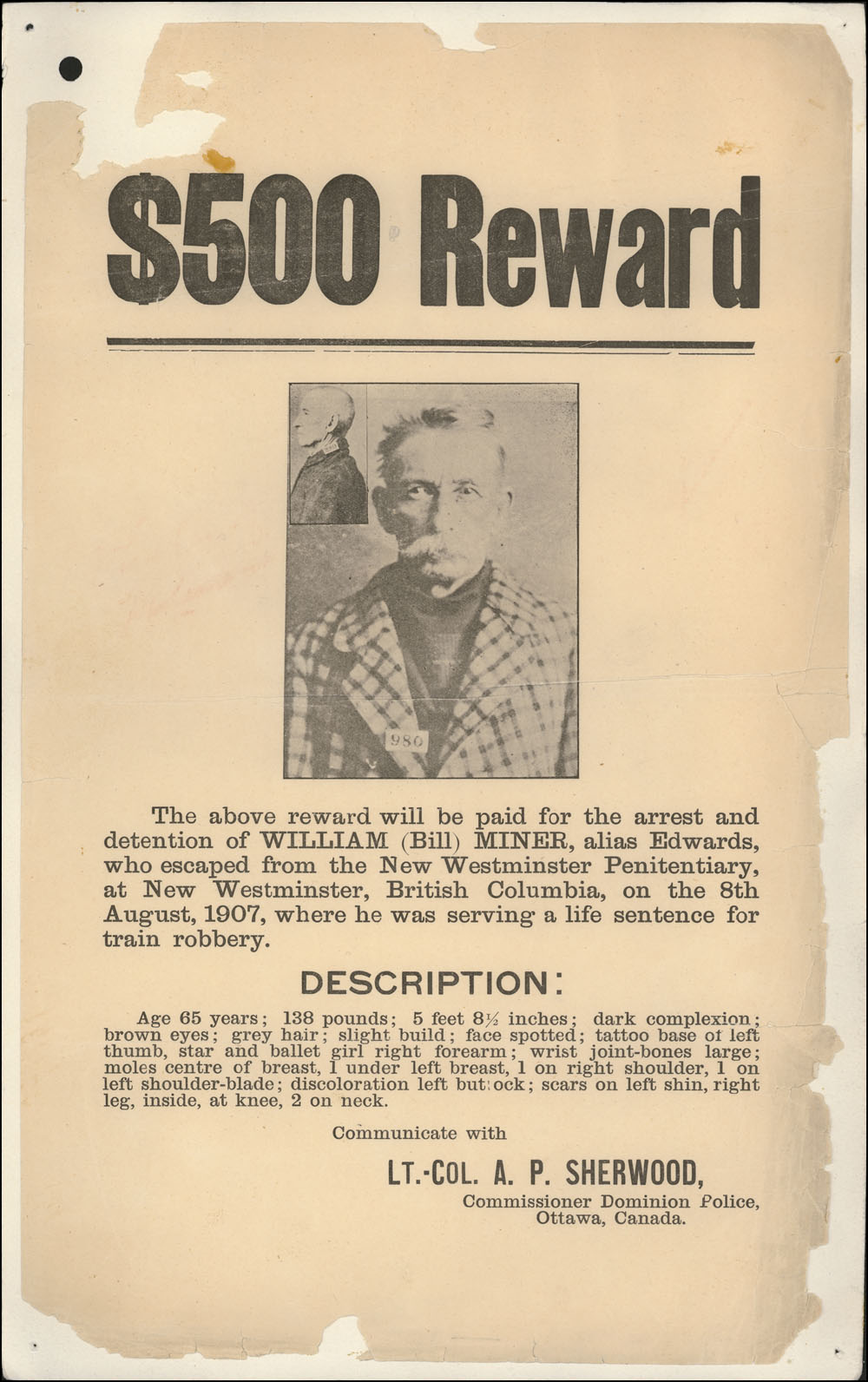

Bill Miner, the notorious “Gentleman Bandit,” had used that same underbrush to affect the prison’s most high-profile escape back in 1907 (Miner’s escape took place before the area was being used as a graveyard), and despite a province-wide manhunt, was never recaptured in Canada.

Reward notice for Bill Miner. Photo from Library and Archives Canada.

Lewis Colquhoum, one of Miner’s accomplices (the gang was caught during a botched train robbery in the B.C. Interior), wasn’t quite so lucky, and likely ended up in Boot Hill himself after dying of tuberculosis in 1911 (the exact location of Colquhoum’s body is unknown, and no grave marker has yet been identified).

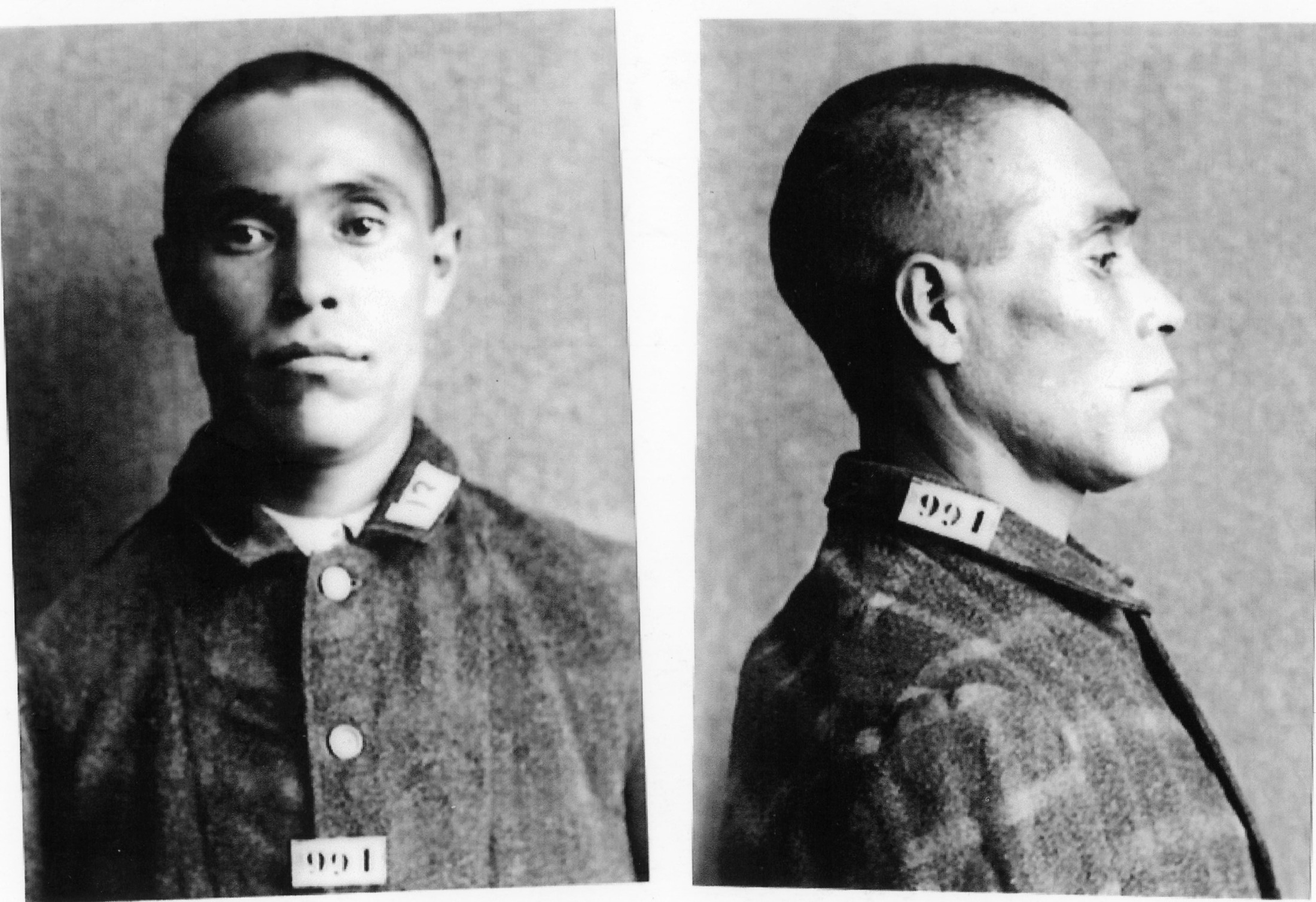

Sook Sias (Prisoner #999), another of Boot Hill’s best-known residents, isn’t even interred on the premises. A First Nations member of the Laich-Kwil-Tach community in Greene Point, B.C., Sias was incarcerated twice at the B.C. Penitentiary (for murder and manslaughter, respectively). Following his death in 1933, his remains languished in the cemetery, and were even accidentally unearthed once in 1955, after heavy rains eroded the edge of the ravine so severely that his casket was left exposed. In 2004, thanks to extensive research conducted by Campbell River historian (and distant Sias relative) Candy-Lea Chickite, Sias’ body was located, disinterred, and returned to his ancestral homeland.

Sook Sias’ mugshot on admission to the B.C. Penitentiary in 1906. Photo from B.C. Penitentiary Collection.

And Sias isn’t the only member of a marginalized community who met their end in the B.C. Penitentiary. James Tarasoff (Prisoner #4214), was one of three Doukhobors who died in 1933. For much of the mid-20th century, the province’s Doukhobor population regularly clashed with police and authorities, staging mass protests (which involved public nudity), and committing acts of arson. In 1931 alone, more than 600 Doukhobors were sentenced for public nudity, a response to what the pacifist sect termed undue government interference (such as mandatory public school). The influx of Doukhobor prisoners was so massive that, during this period, special prisons had to be built to house them. In 1962, Agassiz Mountain Prison was specifically constructed to house the Doukhobor prison population.

After more than 100 years of service, the B.C. Penitentiary was demolished in 1980. Today, very little of the prison survives, besides Boot Hill, a few administrative buildings, and the old Gate House (now a restaurant). And the records that have allowed historians to determine the identity of the Boot Hill bodies nearly didn’t survive either, until the timely intervention of Tony Martin, the facility’s former bookkeeper, who rescued all manner of historical records from the trash heap.

“During the process I was told by a couple of friends that there were all kinds of things being sent to the dump, which they didn’t think should be,” Martin recalled in a 2009 reminiscence transcribed and collected for the Old Courthouse/John Howard Society’s Anthony Martin BC Penitentiary Collection.

“So, I suggested they sidetrack them, put them in a barn, which was actually in what used to be a piggery, and I would look at them later, and as a result of this, saved as much as I could from going to the dump.”

Among the artifacts Martin rescued was prison furniture, mug shots, correspondence, and decades of official reports. The Boot Hill site remained largely overgrown and forgotten until 2018, when, at the urging of historians, the City of New Westminster pledged to maintain the site.

A small sign now commemorates the site of the Boot Hill cemetery. Photography by Jesse Donaldson.

Today, the lawn is manicured, a burial plot—drawn from Martin’s research—lays out the location of each marker, and signage has been erected detailing the long-neglected history of Boot Hill for interested passers-by, ensuring that, unlike the men buried within, the cemetery itself will never again be forgotten.

See more of our “Hidden Vancouver” series here.