From the outside, the apartment building at 1310 Burnaby Street is unremarkable—a quaint, two-storey walkup nestled amongst a half-dozen other such buildings, in a quiet section of the West End, just a few blocks from English Bay.

But 60 years ago this month, in the bedroom of Apartment 201, a macabre piece of Vancouver history was made. It was October 14, 1959, and Hollywood star Errol Flynn was having a heart attack. It was his third, and he wouldn’t survive it.

In the days before the incident, there were numerous indications that the actor was on his last legs; notorious for his heavy drinking, hard living, and insatiable sexual appetite, Flynn already looked far older than his 50 years. In addition to cirrhosis, he was dealing with recurrent malaria, an intestinal infection, and chronic back pain (which, for a time, he had used heroin to combat), and had already suffered two previous heart attacks. In fact, just one month earlier, his doctor had conducted an ECG and had cautioned Flynn to scale back his lifestyle.

But Flynn needed money.

A swashbuckling star of the silver screen throughout the ’30s and ’40s, his career had been rocked by a series of scandals (including two different charges of statutory rape) and had yet to fully recover. A recent, never completed film production about William Tell, which he had helped produce, had been a financial disaster, and his autobiography, My Wicked, Wicked Ways, had yet to hit bookstore shelves. So, seeking quick cash, he had agreed to sell his prized yacht to George Caldough, a 30-year-old stock promoter who lived in the British Properties.

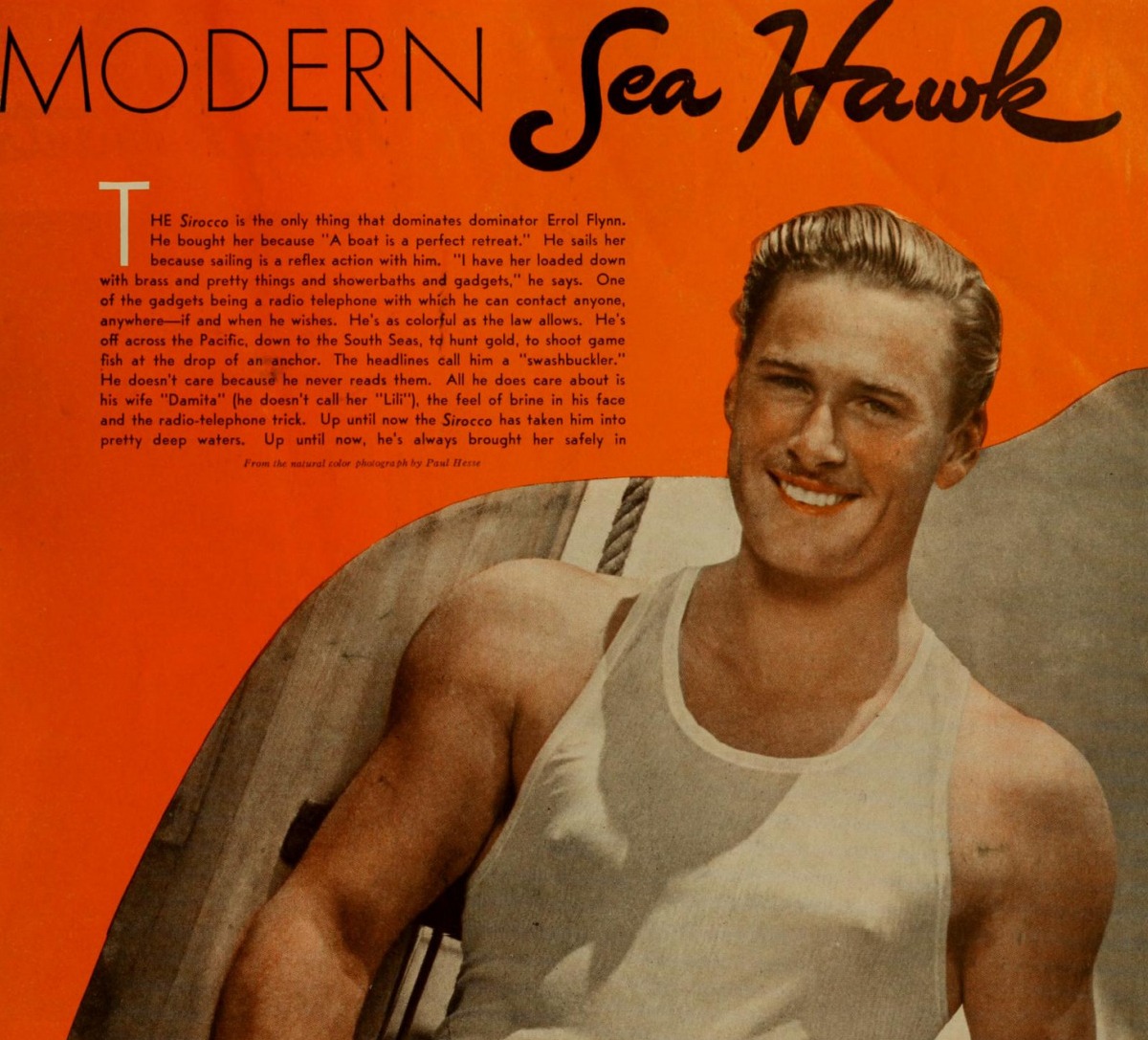

Errol Flynn in a colour publicity still for The Sea Hawk.

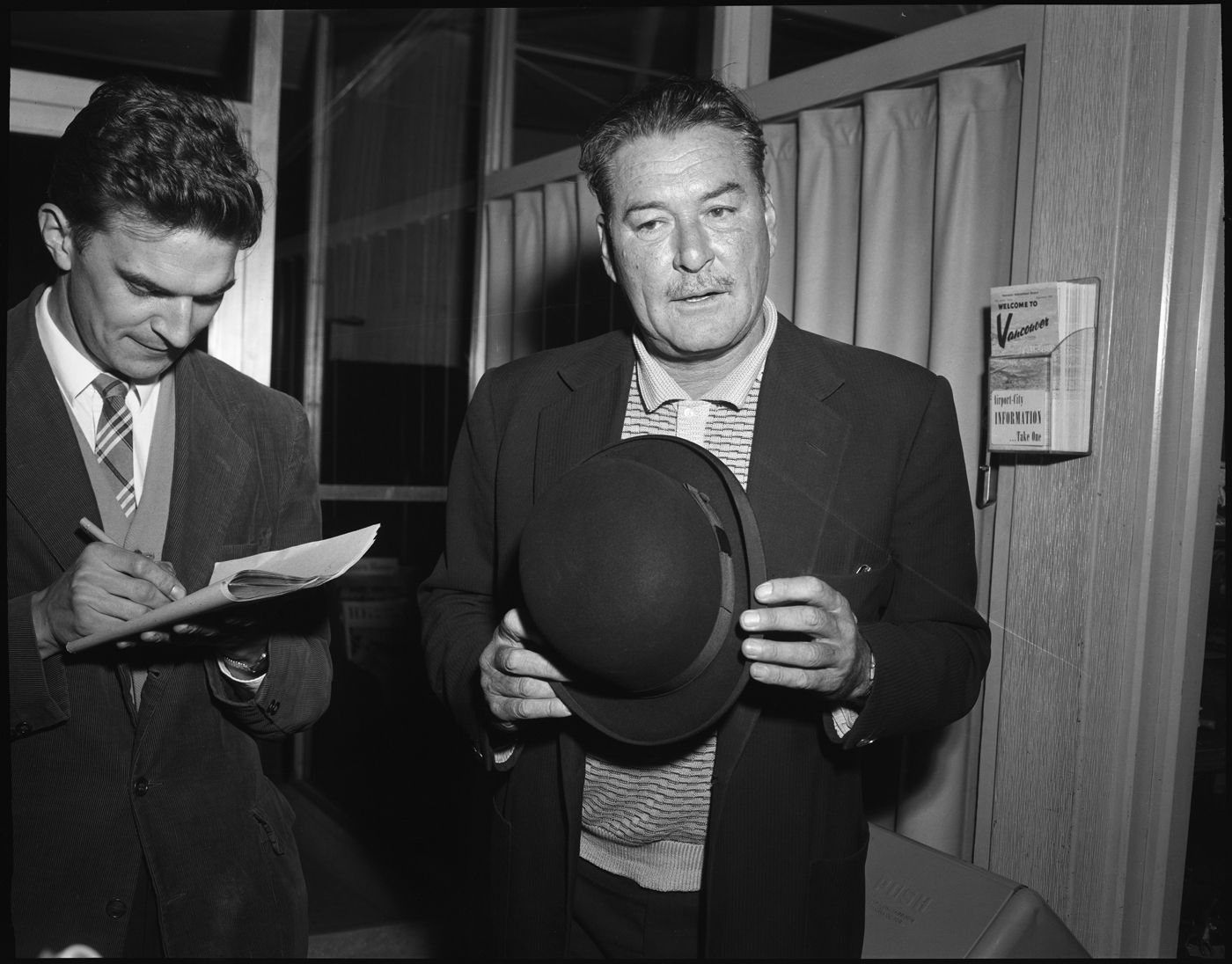

Despite his brief stay in the city, Flynn had already caused quite a stir when he arrived at the airport with his 17-year-old lover, Beverly Aadland; when asked by a female Vancouver Sun journalist why he preferred the company of such young women, Flynn’s reply was, the paper noted, “brief, succinct, direct, detailed, and completely unsuited for a family journal” (it was later reported to have been “because they f— so good”).

Flynn and Aadland remained Caldough’s houseguests for most of that week, drinking and carousing at a number of local nightspots, with the intention of flying out of Vancouver on the afternoon of the 14th. For several days, Flynn had been complaining about worsening pain in his back and legs (he was bedridden for several days), and while en route to the airport, he demanded that Caldough track down someone who could help.

At approximately 3:45 p.m., the party arrived at 1310 Burnaby Street—the home of Dr. Grant Gould. Gould, a friend of Caldough’s (and uncle of Canadian piano prodigy Glenn Gould), had never met Flynn before, but he nonetheless administered a shot that greatly lifted the actor’s spirits. Flynn then went on to regale Gould and his guests (which included Art Cameron, manager of the nearby Sylvia Hotel) with stories of his life in Hollywood, before retiring to Gould’s bedroom to lie down.

Errol Flynn in Vancouver, date unknown. Image courtesy of Vancouver Public Library.

Fifteen minutes later, when Aadland went to check on him, she found he had stopped breathing.

She burst into the living room shouting: “Something is terribly wrong with Errol,” witnesses reported. “He’s turned black.”

Aadland and Gould attempted to revive Flynn—first with amyl nitrite, then with a shot of adrenaline directly to the heart, according to the next day’s report in the Vancouver Sun. Immediately thereafter, Aadland descended into hysterics, smashing her head against the railing of Gould’s balcony before being restrained by the other guests, who feared she might throw herself over the edge. Despite 90 minutes of lifesaving efforts by fire and emergency crews, Flynn never regained consciousness and was shortly thereafter pronounced dead.

From there, if coroner Glen McDonald’s account is to be believed, the story became more macabre still.

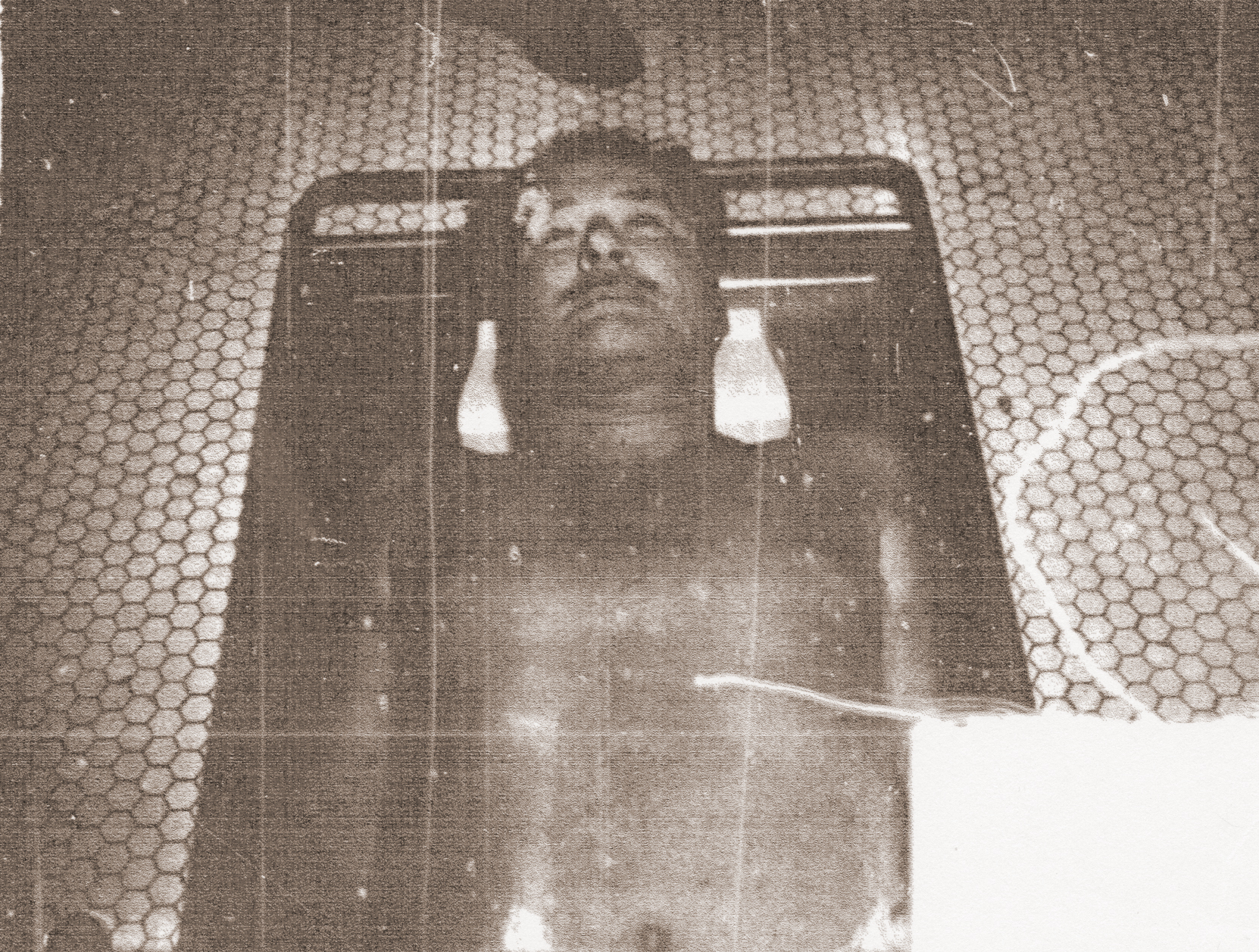

Errol Flynn’s autopsy photo, taken October 14, 1959.

“I was about to leave [the] office when the telephone rang,” McDonald wrote in his autobiography, How Come I’m Dead? “I was looking forward to a gin and tonic.”

News of Flynn’s passing travelled fast, and the coroner’s office was soon besieged with calls from Vancouverites clamouring to view his body. The first to see it were McDonald and chief pathologist Tom Harmon, who were tasked with doing an initial examination before the body was sent to Los Angeles. Their findings were largely consistent with the L.A. coroner’s report—the cause of death having been a heart attack—but, during the final moments of examination, McDonald and Harmon discovered something else: several large venereal warts on the end of Flynn’s penis.

“Tom seemed fascinated,” McDonald wrote, saying, “‘Look, I’m going to be lecturing at the Institute of Pathology, and I just thought it might be of interest if I could remove these things and fix them in formaldehyde and use them as a visual aid.’”

“No way!” McDonald replied. “We’re not going to do that. I don’t want anything done that isn’t relevant to the case because we’re really in the limelight tonight. We’re on the hot seat. How can we send Mr. Flynn back to his wife with part of his bloody endowment missing?”

However, a few moments later, when McDonald returned to the observation room, he discovered something was missing.

“The first thing I noticed was that the VD warts had gone—vanished from the end of Mr. Flynn’s penis,” McDonald continued. “Then I spotted a jar of formaldehyde on a shelf that looked suspiciously like it might contain VD warts.”

The pair got into a heated argument, which quickly descended into hysterical laughter. Finally, McDonald managed to convince Harmon to return the warts, which they reattached to the cadaver using “the good offices of scotch tape.”

“Maybe the Doc had never seen warts of that enormity,” McDonald concluded. “Maybe he wanted a souvenir. I never did figure out why the temptation had been too great […] And I was relieved to learn later, talking with the Chief Coroner in Los Angeles, that a further autopsy was performed and the results concurred in every respect with what we had found.”

According to McDonald, the Scotch tape was never mentioned.

![Hollywood C.C. and Vancouver [at] Brockton Point. Group portrait showing Errol Flynn (seated in front row far left).](https://montecristomagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Hollywood-C.C.-and-Vancouver-at-Brockton-Point.-Group-portrait-showing-Errol-Flynn-seated-in-front-row-far-left..jpg)

Hollywood C.C. at Brockton Point. Group portrait showing Errol Flynn (seated in front row far left). Photo courtesy of the City of Vancouver Archives Port P1494.2.

“I haven’t accepted his death yet,” Aadland told the Sun two days later. “I haven’t gone beyond today. I promised him if anything happened I would go ahead in the Flynn tradition—live for today and have a wonderful time doing it.”

And, according to Aadland, when it came to his own death, Flynn had always treated the matter with his own particular brand of dark humour.

“He always said: ‘If anybody comes to my funeral, I’ll cut them out of my will.’”

Read more history stories here.